Eerlijk is eerlijk, Frankrijk staat bekend om de drank: naast bier, sherry, port, champagne en cognac is daar natuurlijk de wijn:

France is one of the most famous and prestigious wine regions of the world (www.kamiljuices.com/wines-france.html). France created the modern wine industry (www.slideshare.net/JMcInerny/french-wine-in-a-flash)

You cannot go to France without experiences (and hopefully enjoying) the amazing food and wine. Wine is such an important part of the country’s national pride and identity that many French simply do not sit down to a meal without a bottle on the table (www.francetravelguide.com/french-wine-understanding-the-4-categories.html). Zie hier een top 10 van Franse wijnen. Maar er zijn heel veel stijlen, zoals de GSM van de Rhonevallei (Grenache, syrah, Mourvedre), zoals in deze presentatie te zien. Wie gaat al die stijlen nu ooit allemaal weten? Daar is meer informatie voor nodig, zoals deze website: www.terroir-france.com/wine/... met een mooie woordenlijst (maar terroir staat daar niet in...).

France is the birthplace of modern winemaking and serves as a model for wine production internationally. Even though it’s only about the size of Texas, France produces between 7 and 8 billion bottles per year and has the second-largest total vineyard area in the world. France has also been making, perfecting, and exporting their wines since the 6th century BCE, and the country has been associated with winemaking since before Roman times.

The tradition and history surrounding French wines are not the only things that make them so treasured. The fact of the matter is that French vineyards produce some of the highest quality wines in the world. France is also the source of many grape varieties (like Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Sauvignon Blanc, etc.) that are now planted around the world, and French wine-making practices are copied in many other countries.

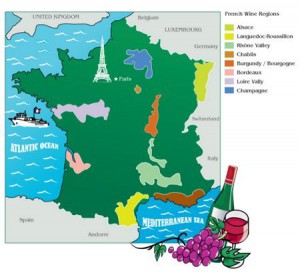

So, for those of us who are not sommeliers or wine experts, let’s brush up on some basic knowledge of French wines and the regions they come from (www.francetravelguide.com/a-guide-to-french-wine.html).

Ik onderscheid wijn in kleur (rood, wit of rosé), maar dat schijnt niet echt de methode te zijn. Al zal dat in het café vaak anders zijn. daar merkte ik het volgende onderscheid: rood of wit / zoet of droog?

Wine can be categorized in different ways, but basically, there are mainly two different ways to consider. These 2 ways are based on 2 philosophies which have not always gone along together very well. On one hand, wine can be categorized out from its geographical origin. On the other hand, the wine can be categorized out from which wine grape variety that has been used for the winemaking. The first way based on the geographical origin is usually defended by the wine producing countries in Europe and the second way, based on which grape variety that has been used, is usually defended by what we call the New World.

In France, when speaking about different wine varieties, it's primarily the geographical origin, which through the appellation system, is commissioned to organize the French wine production. ...Only 10 years ago, few consumers in France asked themselves which grape variety or varieties that were used in the winemaking. Wine was categorized (and actually still is today!) depending on its geographic origin. What in French is called «terroir» is the most important concept when classifying wine. The "terroir" can shortly be translated into the soil, but in real, "the terroir" is a much broader concept which not only takes into account the soil (terre), but also the vine's exposure to the sun, the climate, the wind, the height above sea level. In other words, it's the common denominator for everything that influences the grapes and thereby has an impact on the character of the wine. Historically, the appellations system has been a very important concept in France, both in the winemaking and also to the man in the street. Good wines belong to an appellation and even today, there are few who are interested in what grape variety that has been used for producing the wine.

A French exception is Alsace, where the name of the grape variety was added to the appellation name when the Alsace appellation was created in 1962. For example you say AOP Alsace Riesling or AOP Alsace Gewurtztraminer, not only Alsace. But generally speaking, the wine's geographical origin and its terroir play a more significant role in France than just the name of a grape variety. As an example, few consumers in France would ask for a «Chardonnay» in a retail store . They would rather ask for a white wine from Burgundy with all its hundreds of various geographical names ...

In contrast to this terroir philosophy, there are those who primarily are interested in the grape varieties, of which the wine has been produced. This terminology derives mainly from the new world wines which, less tied to tradition and history, have been able to experiment and produce varietal wines made from only one grape variety and where generally speaking, wine producer have been much more interested in the grape varieties rather than the regional origine (www.ivinio.com/blog/2015/08/grape-variety-or-terroir-/).

To drink good wine, you can actually consider both the terroir philosophy and the grape varietal philosophy. It's a good thing that there's an appellation system that structures the wine and defend tradition, but it is also good that there are winemakers who produce good varietal wines. Anything that increases variety and range is in our view positive, of course provided that consumers can easily understand what they are buying.

The irony is that nature itself unites the two concepts since vines of the same grape variety, but from 2 different origines, give different characteristics to the wines as well when vinified separately. There are e.g. in southern France, wine growers who cultivates both French and Italian Vermentino on the same land and the plants provide two different white wines with different taste! The terroir philosophy is an uncompromisingly important part of the character of a wine, but also, the grape variety itself has clones which make wines with different characters even if the vines are grown in the same place! Wine is - despite the big companies trial to prove the opposite - an agricultural product, not an industrial product where the end product is always the same. But that's also the charm of wine (www.ivinio.com/blog/2015/08/grape-variety-or-terroir-/).

French wine originated in the 6th century BC, with the colonization of Southern Gaul by Greek settlers. Viticulture soon

flourished with the founding of the Greek colony of Marseille. The Roman Empire licensed regions in the south to produce wines. St. Martin of Tours (316–397) was actively engaged in both spreading Christianity and planting vineyards. During the Middle Ages, monks maintained vineyards and, more importantly, conserved wine-making knowledge and skills during that often turbulent period. Monasteries had the resources, security, and motivation to produce a steady supply of wine both for celebrating mass and generating income. During this time, the best vineyards were owned by the monasteries and their wine was considered to be superior. Over time the nobility developed extensive vineyards. However, the French Revolution led to the confiscation of many of the vineyards owned by the Church and others.

The advance of the French wine industry stopped abruptly as first Mildew and then Phylloxera spread throughout the country, indeed across all of Europe, leaving vineyards desolate. Then came an economic downturn in Europe followed by two world wars, and the French wine industry didn’t fully recover for decades. Meanwhile competition had arrived and threatened the treasured French “brands” such as Champagne and Bordeaux. This resulted in the establishment in 1935 of the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée to protect French interests. Large investments, the economic upturn following World War II and a new generation of Vignerons yielded results in the 1970s and the following decades, creating the modern French wines we know today (http://034dc62.netsolhost.com/WordPress/2012/07/18/all-you-need-to-know-about-french-wine/).

All common styles of wine – red, rosé, white (dry, semi-sweet and sweet), sparkling and fortified – are produced in France. In most of these styles, the French production ranges from cheap and simple versions to some of the world’s most famous and expensive examples. An exception is French fortified wines, which tend to be relatively unknown outside France.

In many respects, French wines have more of a regional than a national identity, as evidenced by different grape varieties, production methods and different classification systems in the various regions. Quality levels and prices vary enormously, and some wines are made for immediate consumption while other are meant for long-time cellaring.

If there is one thing that most French wines have in common, it is that most styles have developed as wines meant to accompany food, be it a quick baguette, a simple bistro meal, or a full-fledged multi-course menu. Since the French tradition is to serve wine with food, wines have seldom been developed or styled as “bar wines” for drinking on their own, or to impress in tastings when young (http://034dc62.netsolhost.com/WordPress/2012/07/18/all-you-need-to-know-about-french-wine/).

French wine is divided into categories a couple of different ways:

Wines are divided by terroir, which links the style of wine to the specific location where the grapes were grown and the wine made (Burgundy, for example, is made in the Burgundy region).

Wines are also categorized by the Appellation d’Origine Controlee (AOC) system, which has strict rules defining grape varieties and winemaking practices allowed in each of France’s several hundred geographically defined “appellations.” An appellation can be as small as a specific vineyard or village, or cover an entire region (www.francetravelguide.com/a-guide-to-french-wine.html).

Knowing and understanding French wines is critical to enjoying the wide world of wine to its fullest, yet French wine classification systems and resulting label layouts can get confusing quickly for consumers raised on New World wine labels highlighting grape names over place names.

Remember, the place, not the grape, is the priority when naming and labeling French wines. Bordeaux is a place—a city, in fact—right off the Atlantic Coast. Likewise, Champagne is a place—a region just east of Paris. Specific grapes grow really well in certain places, making a location like Bordeaux famous for growing Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, and a region like Champagne ideal for Chardonnay and Pinot Noir—which also happen to be the top grape varieties used for making the best bubbles of Champagne (www.idiotsguides.com/food-and-drink/wine-and-drink/understanding-french-wine/).

The concept of Terroir, which refers to the unique combination of natural factors associated with any particular vineyard, is important to French vignerons. It includes such factors as soil, underlying rock, altitude, slope of hill or terrain, orientation toward the sun, andmicroclimate (typical rain, winds, humidity, temperature variations, etc.). Even in the same area, no two vineyards have exactly the same terroir, thus being the base of the Appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC) system that has been model for appellation and wine laws across the globe. In other words: when the same grape variety is planted in different regions, it can produce wines that are significantly different from each other. In France the concept of terroir manifests itself most extremely in the Burgundy region. The amount of influence and the scope that falls under the description of terroir has been a controversial topic in the wine industry (http://034dc62.netsolhost.com/WordPress/2012/07/18/all-you-need-to-know-about-french-wine/).

Decoding French Wine: A Beginner’s Guide to Enjoying the Fruits of the French Terroir is a short, almost pocketbook guide, written to help early stage wine drinkers navigate the world of French wine so they feel comfortable opening up a French wine list and understand exactly what they are ordering and why (www.amazon.com/Decoding-French-Wine-Beginners-Enjoying-ebook/dp/B007NM91GW).

The French word terroir is used to describe all the ecological factors that make a particular type of wine special to the region of its origin. James E. Wilson uses his training as a geologist and his years of research in the wine regions of France to fully examine the concept of terroir. The result combines natural history, social history, and scientific study, making this a unique book that all wine connoisseurs and professionals will want close at hand. In Part One Wilson introduces the full range of environmental factors that together form terroir. He explains France's geological foundation; its soil, considered the "soul" of a vineyard; the various climates and microclimates; the vines, their history and how each type has evolved; and the role that humans--from ancient monks to modern enologists-- (www.amazon.com/Terroir-Geology-Climate-Culture-Making/dp/1891267221).

Terroir is a holistic concept that relates to both environmental and cultural factors that together influence the grape growing to wine production continuum. The physical factors that influence the process include matching a given grape variety to its ideal climate along with optimum site characteristics of elevation, slope, aspect, and soil. While some regions have had hundreds and even thousands of years to define, develop, and understand their best terroir, newer regions typically face a trial and error stage of finding the best variety and terroir match. This research facilitates the process by modeling the climate and landscape in a relatively young grape growing region in Oregon, the Umpqua Valley appellation. The result is an inventory of land suitability that provides both existing and new growers greater insight into the best terroirs of the region (https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/gc/article/view/2779/3266).

The beautiful French word Terroir as defined by Winefolly is “how a particular region’s climate, soils and aspect (terrain) affect the taste of wine. Some regions are said to have more ‘terroir’ than others.” Here is a graphic from Winefolly to further illustrate the meaning of terroir (http://rockinredblog.com/2015/04/17/babcock-winery-a-lesson-in-terroir/):

Wine isn’t the only entity encasing terroir. Terroir can apply to almost anything that is affected by environment and cultural circumstances: cheese, coffee, charcuterie, marijuana and humans. Think about regional accents in language – these are physical productions of terroir (www.obsev.com/food/terroir-wines-biggest-mystery-debunked.html).

Climate

The physical environment in which grapes grow makes a physical impact on the way a wine tastes. It is exactly the climate of a region that determines what type of grape varieties can be planted there. This is exactly why grapes grown in cooler climates have higher acidity levels than those grown in warmer regions.

Soil

Contrary to belief, a wine with an “earthy” characteristic doesn’t necessarily have to do with the soil the grapes were grown in. It certainly can, but science hasn’t proved anything on this matter. The concept of a wine’s "minerality" could just as easily be attributed to a nearby ocean breeze. The commonly used wine adjective “slatey” (mmm German Riesling) could just as easily be attributed to the steel tank the wine was aged in. The density, consistency, mineral deposits and moisture levels in soil all affect the way the grape ripens.

Terrain

Differences in the way a vineyard is sloped, the altitude and elevation, and the direction the vines face (determining amount of sunlight, wind, etc) are all factors that affect the grapes. For instance, many vineyards in Argentina are located at higher elevations between 2,000 and 3,000 feet, giving many of these wines a fresh acidity that is only retained from the mountain’s cooler temperatures.

Tradition

Terroir has a strong cultural side. Grape juice wouldn’t be turned into wine without someone wishing they had some booze. Terroir is a partnership between the winemaker and the grapes. Of course, human intervention can heighten or lessen the expression of environmental influence in wine depending on the winemaker’s style and grip on the wine (think technique and level of ripeness when grapes are picked.) (www.obsev.com/food/terroir-wines-biggest-mystery-debunked.html)

Terroir remains something that we all want to believe in. It gives us something to think deeply about. It’s our Proustian transporter to vacations past. It justifies more and greater purchases. It satisfies our thirst for subtle social differentiation. Terroir is a matter of faith, and faith is, if nothing else, an unyielding belief in the unknowable.

In spite of its hazy existence, some generalized assertions about terroir are possible, two of which I’d like to mention here. First, place does matter. Campaigners for terroir are selling more than just tulips in Amsterdam. There is a legitimate product behind the claims. The American wine critic David Schildknecht stands as one of the most sensible and passionate advocates of terroir. Equally passionate (if a bit more quixotic) is Terry Theise, a renowned importer whose heartfelt catalogs have become cult reading among terroir buffs. These intelligent and experienced voices leave us no doubt that soil and climate have some role to play in shaping taste in wine. Second, terroir is marketing. In spite of terroir’s genuineness, doubters and naysayers can and do have reasonable suspicions. Growers, importers, distributors, critics, and merchants have frequently been less than forthcoming about the technological side of the winemaking process. The fact is that the taste profile of the great majority of wines purchased in the U.S.—smoke, vanilla, espresso—is determined not by nature but by overt and intrusive cellar practices. To be clear, this is not unethical or even out of the ordinary, but in spite of what the label may say, this is not terroir (http://tempestinatankard.com/2013/12/16/terroir-and-the-making-of-beer-into-wine/).

As the meaning of "terroir" continues to be hotly disputed, settling on a definition that considers soil, topography and climate, as well as human intervention, proves very complex (www.winebusiness.com/wbm/?go=getArticleSignIn&dataId=42095).

In 1935 numerous laws were passed to control the quality of French wine. They established the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée system, which is governed by a powerful oversight board (Institut National des Appellations d’Origine, INAO). Consequently, France has one of the oldest systems for protected designation of origin for wine in the world, and strict laws concerning winemaking and production. Many other European systems are modelled after it. The word “appellation” has been put to use by other countries, sometimes in a much looser meaning. As European Union wine laws have been modelled after those of the French, this trend is likely to continue with further EU expansion.

French law divides wine into four categories, two falling under the European Union’s Table Wine category and two falling under the EU’s Quality Wine Produced in a Specific Region(QWPSR) designation. The categories and their shares of the total French production for the 2005 vintage, excluding wine destined for Cognac, Armagnac and other brandies, were:

Table wine:

Vin de Table (11.7%) – Carries with it only the producer and the designation that it is from France.

Vin de Pays (33.9%) – Carries with it a specific region within France (for example Vin de Pays d’Oc from Languedoc-Roussillon or Vin de Pays de Côtes de Gascogne fromGascony), and subject to less restrictive regulations than AOC wines. For instance, it allows producers to distinguish wines that are made using grape varieties or procedures other than those required by the AOC rules, without having to use the simple and commercially non-viable table wine classification. In order to maintain a distinction from Vin de Table, the producers have to submit the wine for analysis and tasting, and the wines have to be made from certain varieties or blends.

QWPSR:

Vin Délimité de Qualité Supérieure (VDQS, 0.9%) – Less strict than AOC, usually used for smaller areas or as a “waiting room” for potential AOCs. This category was abolished at the end of 2011.

Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC, 53.4%) – Wine from a particular area with many other restrictions, including grape varieties and winemaking methods.

The wine classification system of France has been under overhaul since 2006, with a new system to be fully introduced by 2012. The new system consists of three categories rather than four, since there will be no category corresponding to VDQS from 2012. The new categories are:

Vin de France, a table wine category basically replacing Vin de Table, but allowing grape variety and vintage to be indicated on the label.

Indication Géographique Protégée (IGP), an intermediate category basically replacing Vin de Pays.

Appellation d’Origine Protégée (AOP), the highest category basically replacing AOC wines.

The largest changes will be in the Vin de France category, and to VDQS wines, which either need to qualify as AOP wines or be downgraded to an IGP category. For the former AOC wines, the move to AOP will only mean minor changes to the terminology of the label, while the actual names of the appellations themselves will remain unchanged (http://034dc62.netsolhost.com/WordPress/2012/07/18/all-you-need-to-know-about-french-wine/).

The French take their wines very seriously. Since 1935, France has had the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée system, which is governed by a powerful oversight board called the INAO (Institut National des Appellations d’Origine). This is one of the oldest and strictest systems for designation and quality control in the world. Under this system, France established four different quality levels in order to categorize their many wines. This means that no matter what region the wine is from (Bordeaux, Loire, Rhône, Burgundy) or what kind of wine it is (red, white, rosé, sparkling), all wines will fall under one of four categories of quality levels (www.francetravelguide.com/french-wine-understanding-the-4-categories.html).

AOC (Vins d'Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée) wines are at the upper echelon of the French wine classification system. These wines must meet key criteria in terms of vineyard and wine-making practices, as well as requirements for minimum alcohol levels, and they must adhere to rules for using only the permitted grape varieties grown within the specific appellation boundaries.

AOC wines often have a specific place name on the label between the words Appellation and Contrôlée. For example, a wine carrying a label from grapes sourced from a specific subregion of the famous Loire Valley like Sancerre reads Appellation Sancerre Contrôlée. At other times, the names of the general region or a small village appear on the label, followed by the initials AOC (www.idiotsguides.com/food-and-drink/wine-and-drink/understanding-french-wine/).

VDQS (Vins Délimités de Qualité Supérieure) wines are loosely translated as "wines of superior quality" and represent one step down in label requirements from the AOC wines. Often the vineyards may harvest grapes at higher yields, reducing the quality and concentration compared to the AOCs. The initials VDQS or the full-blown phrase appears at the bottom of the label (www.idiotsguides.com/food-and-drink/wine-and-drink/understanding-french-wine/).

Vins de Pays are considered "country wines" and are defined by a specific place or, more often, a large region. The rules and regulations for obtaining a Vins de Pays designation are significantly looser than the AOC or VDQS standards. The Languedoc-Roussillon region puts out plenty of good, everyday Vins de Pays wines each year, wearing the label Vins de Pays de Languedoc-Roussillon, inferring they're country wines from the French region of Languedoc-Roussillon (www.idiotsguides.com/food-and-drink/wine-and-drink/understanding-french-wine/).

Vin de Table: These are entry-level French wines that carry with them only the distinction that they were produced in France. You will often find these types of wines served in carafes in restaurants as the house wine—usually only as “house red” and “house white.” While of the lowest distinction in France, these wines are typically quite good for their low prices and you can usually pick up a bottle of vin de table for only a couple euros.

Vin de Pays: These wines carry the distinction of what region they were produced in (for example, Côtes du Rhône from the Rhône Valley or Vin de Pays d’Oc from the Languedoc-Roussillon region). This distinction allows producers to distinguish what grape varieties were used in production. These wines also must be submitted for wine analysis and tasting to ensure quality. You’ll usually get the biggest bang for your buck with these wines as some of them are exceptionally good without the high price tag of AOC wines.

VDQS (Vin Délimité de Qualité Superieure): This category is often considered the “waiting room” for wines trying to get an AOC rating. While they only account for 2% of total French wines, it is important to understand this category as you can score a very high quality bottle for a lower price.

AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée): This is highest quality level of French wine, with strict restrictions based on grape varities and winemaking methods. These wines are also subject to tasting and evaluation from the INAO (which is an awesome job if you ask me). In years with favorable vintage conditions, there are usually more AOC-rated wines but this is an increasingly large group of French wines, as vineyards in France are attempting to find their niche in the high quality (and expensive) wine market. 2005 was a particularly favorable year in France, leading to a higher number of vintage AOC bottle ratings. These wines are the most coveted in France (www.francetravelguide.com/french-wine-understanding-the-4-categories.html).

Wine is produced in several regions throughout France, in quantities between 50 and 60 million hectolitres per year, or 7–8 billion bottles. France has the world’s second-largest total vineyard area, behind Spain, and is in the position of being the world’s largest wine producer losing it once (in 2008) to Italy. French wine traces its history to the 6th century BC, with many of France’s regions dating their wine-making history to Roman times. The wines produced today range from expensive high-end wines sold internationally, to more modest wines usually only seen within France.

Two concepts central to higher end French wines are the notion of “terroir”, which links the style of the wines to the specific locations where the grapes are grown and the wine is made, and the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) system. Appellation rules closely define which grape varieties and winemaking practices are approved for classification in each of France’s several hundred geographically defined appellations, which can cover entire regions, individual villages or even specific vineyards (http://034dc62.netsolhost.com/WordPress/2012/07/18/all-you-need-to-know-about-french-wine/).

The recognized wine producing areas in France are regulated by the Institut National des Appellations d’Origine – INAO in acronym. Every appellation in France is defined by INAO, in regards to the individual regions particular wine “character”. If a wine fails to meet the INAO’s strict criteria it is declassified into a lower appellation or even into Vin de Pays or Vin de Table. With the number of appellations in France too numerous to mention here, they are easily defined into one of the main wine producing regions listed below (http://034dc62.netsolhost.com/WordPress/2012/07/18/all-you-need-to-know-about-french-wine/).

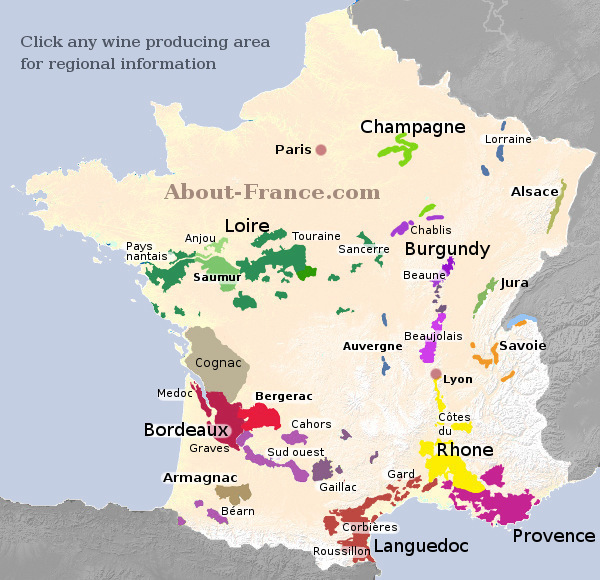

Wine Regions of France

Alsace: This area in France borders Germany and is primarily known for its white and rosé wines. Sparkling sweet wines are also produced in this region, as the chilly temperatures are often best for making bubbly.

Bordeaux: This large region along the southern Atlantic coast of France has a long history of exporting wines and is known mostly for its rich, complex reds. In fact, Bordeaux wines are usually a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. However, while Bordeaux tends to be synonymous with reds, the region is also well known for its famous sweet white wine from Sauternes, usually paired with foie gras.

Burgundy: This area in eastern France is known for its bold Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Burgundy actually has the largest number of appellations of any other region in the country, and is frequently divided into smaller subdivisions. The top wines from the region are found in the Cote d’Or (Gold Coast) – and because these wines command the highest prices, the name seems all too fitting.

Beaujolais: The southern regions of Burgundy near the Rhône valley, makes lighter, fruitier red wines, and is known for the famous Beaujolais Nouveau, a young red wine released each November and consumed by the New Year.

Chablis: A region sometimes lumped in with Burgundy, this area located between the Cote d’Or and Paris produces crisp white wines.

Champagne: This area close to Belgium and Luxembourg was the birthplace of sparkling wine; in recent decades France has protected its signature bubbly by disallowing sparkling wine producers to use the term “champagne” for wines not produced in this area of France. The region has the perfect chilly winter climate to produce Champagne and the most famous brands of bubbly, like Dom Perignon and Veuve Clicquot, have vineyards here.

Languedoc-Roussillon: This is the largest wine region by area in France, and it is where the majority of France’s cheap bulk wines are produced (which are still quite good!). This region is sometimes nicknamed the “wine lake,” and the vintners here are known for being more open to adapting new techniques in winemaking. You’ll often see wines from this region labeled “Vin de Pays d’Oc.”

Loire: This region stretches along the Loire Valley in central and western France and produces France’s highest quality white wines. The upper Loire is known for its Sauvignon Blanc, but the region is also known for its dry, sweet and sparkling wines from Tourraine and Chenin Blanc, as well as its mild reds from Saumur (www.francetravelguide.com/a-guide-to-french-wine.html).

Provence: Southeastern France near the Mediterranean coast is one of the warmest regions of France, and as a result produces mostly white and rosé wines. Bordering the southern Rhône region, Provence has very similar wines, and is also home to some prestigious wine estates.

Rhône: The Rhône Valley in Southeastern France along the Rhône River is known for mostly for its red wines and competes with Bordeaux as a major producer and exporter of French red wines.

Savoie: This region in the French Alps bordering Switzerland is mostly known for its cheeses, great skiing and mountain vistas, but the region also produces some excellent white wines. Because of the chillier mountain temperatures, Savoie grows grapes that are unique to the region and produce distinct wines.

Southwest France: The Sud-Oeust of France is known for its Medieval fortresses like Carcassonne and the Citadelles du Vertige as well as for its rich foods like foie gras and duck confit, and red wines similar to those from Bordeaux and sweet, white wines similar to Sauternes. Many of the wines from this region do not have AOC ratings but are VDQS classified, which basically means they are wines in the “waiting room” for the prestigious AOC classification. These are some of the highest quality wines in France without as big of a price tag (www.francetravelguide.com/a-guide-to-french-wine.html).

When tasting, hold the glass by the stem, as you don’t want your body heat to influence the wine’s properties.

There is no need to drink the wine to fully appreciate it. It’s customary to save the drink for the last sample, as it’s always from the winery’s best wine. If you are visiting a “true” cellar you can spit on the floor; otherwise you’ll find a bucket called un crachoir for you to spit into. Personally, I think it’s the ultimate shame to spit out wine, but if you are stopping at many vineyards and don’t want to be hammered – or if you’re the designated driver – I suppose this is a good idea (www.francetravelguide.com/wine-tasting-in-france.html).

Labels will also indicate where the wine was bottled, which can be an indication as to the quality level of the wine, and whether it was bottled by a single producer, or more anonymously and in larger quantities:

“Mis en bouteille …”

“… au château, au domaine, à la propriété”: these have a similar meaning, and indicate the wine was “estate bottled”, on the same property on which it was grown or at acooperative (within the boundary of the appellation) of which that property is a member.

“… par …” the wine was bottled by the concern whose name follows. This may be the producing vineyard or it may not.

“… dans la région de production”: the wine was not bottled at the vineyard but by a larger business at its warehouse; this warehouse was within the same winemaking region of France as the appellation, but not necessarily within the boundary of the appellation itself. If a chateau or domaine is named, it may well not exist as a real vineyard, and the wine may be an assemblage from the grapes or the wines of several producers.

“… dans nos chais, dans nos caves”: the wine was bottled by the business named on the label.

“Vigneron indépendant” is a special mark adopted by some independent wine-makers, to distinguish them from larger corporate winemaking operations and symbolize a return to the basics of the craft of wine-making. Bottles from these independent makers carry a special logo usually printed on the foil cap covering the cork.

If varietal names are displayed, common EU rules apply:

If a single varietal name is used, the wine must be made from a minimum of 85% of this variety.

If two or more varietal names are used, only the displayed varieties are allowed.

If two or more varietal names are used, they must generally appear in descending order (http://034dc62.netsolhost.com/WordPress/2012/07/18/all-you-need-to-know-about-french-wine/).