An unlimited, free supply of beer – it sounds wonderful doesn’t it? But when it is over one million litres in volume and in a tidal wave at least 15 feet high, as it was in the London Beer Flood on 17 October 1814, the prospect seems less appealing.

Two hundred years ..., a broken vat at the Horse Shoe Brewery on Tottenham Court Road flooded the local area with porter, a dark beer native to the capital, killing eight people and demolishing a pair of homes. George Crick, the clerk on duty, told a newspaper what happened: “I was on a platform about 30 feet from the vat when it burst. I heard the crash as it went off, and ran immediately to the storehouse, where the vat was situated. It caused dreadful devastation on the premises - it knocked four butts over, and staved several, as the pressure was so excessive. Between 8 and 9,000 barrels of porter [were] lost.”

The beer inundated the nearby slum of St Giles Rookery – an area of poverty and vice which inspired Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’ – flooding the cellars where whole families lived. Some of the inhabitants survived by clambering onto pieces of furniture. Others were not so lucky. Hannah Banfield, a little girl, was taking tea with her mother, Mary, at their house in New Street when the deluge hit. Both were swept away in the current, and perished (www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/what-really-happened-in-the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-9796096.html).

Wherever you are at 5.30pm this evening, please stop a moment and raise a thought – a glass, too, if you have one, preferably of porter – to Hannah Banfield, aged four years and four months; Eleanor Cooper, 14, a pub servant; Elizabeth Smith, 27, the wife of a bricklayer; Mary Mulvey, 30, and her son by a previous marriage, Thomas Murry (sic), aged three; Sarah Bates, aged three years and five months; Ann Saville, 60; and Catharine Butler, a widow aged 65. ...victims of the Great London Beer Flood (http://neveryetmelted.com/2014/10/17/great-london-beer-flood-of-1814/) (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

On October 17, 1814, a three-story-high vat of beer exploded inside a London brewery and unleashed a tidal wave of porter that killed eight people in the neighboring tenements (www.history.com/news/the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago).

The London Beer Flood happened on 17 October 1814 in the parish of St. Giles, London, England. At the Meux and Company Brewery on Tottenham Court Road, a huge vat containing over 135,000 imperial gallons (610,000 L) of beer ruptured, causing other vats in the same building to succumb in a domino effect. As a result, more than 323,000 imperial gallons (1,470,000 L) of beer burst out and gushed into the streets. The wave of beer destroyed two homes and crumbled the wall of the Tavistock Arms Pub, trapping teenage employee Eleanor Cooper under the rubble. Within minutes neighbouring George Street and New Street were swamped with alcohol, killing a mother and daughter who were taking tea, and surging through a room of people gathered for a wake.

The brewery was among the poor houses and tenements of the St Giles Rookery, where whole families lived in basement rooms that quickly filled with beer. At least eight people were known to have drowned in the flood or died from injuries (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Beer_Flood).

Het verhaal staat op Wikipedia, dus het zal wel waar zijn...

On Monday 17th October 1814, a terrible disaster claimed the lives of at least 8 people in St Giles, London. A bizarre industrial accident resulted in the release of a beer tsunami onto the streets around Tottenham Court Road (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-London-Beer-Flood-of-1814/).

Two hundred years ago, eight Londoners died in one of the oddest ways imaginable. Or, to invoke the thoroughly British words of the Times' news report on the incident, "The neighbourhood of St. Giles's was thrown into the utmost consternation on Monday night, by one of the most melancholy accidents we ever remember."

On the evening in question—Oct. 17, 1814—one of the vats at the Meux and Co. brewery burst, blowing apart the building's timber walls and sending the equivalent of 3,500 barrels of beer cascading onto the streets.

The ale tsunami demolished two homes as it swept along what is now Tottenham Court Road in Bloomsbury. In other homes, according to the Times report on Oct. 19, 1814, "inhabitants had to save themselves from drowning by mounting their highest pieces of furniture." Others were not so lucky, such as a mother and daughter who had just sat down to tea in their first-floor home: In the evocative words of the Times, the daughter was "swept away by the current through a partition, and dashed to pieces."

In all, eight people died in the London Beer Flood. Five others were injured badly enough to be taken to the hospital, and three brewery employees were rescued by flabbergasted volunteers, who had to wade through waist-deep beer cluttered with debris (http://www.slate.com/blogs/atlas_obscura/2014/10/17/on_this_day_in_1814_the_london_beer_flood_killed_eight_people.html).

Most, if not all, of those who died were poor Irish immigrants to London, part of a mass of people living in the slums around St Giles’s Church, the infamous St Giles “rookeries” (later to be cleaned away by the building of New Oxford Street in 1847). Maurice Donno was very probably Irish, his surname most likely a variation of Donough or something similar (which would make his first name a common Anglicisation of the Irish Muirgheas). Perhaps he knew some of those who died, or were injured, in the Great Beer Flood, or knew people who knew them. It seems very likely he would have gone across the road at some point after the tragedy, to join the hundreds who came to see the destruction wreaked by that dreadful black tsunami of beer (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

This is a picture of the Boston Molasses Disaster.

The building in the top right says SAVANNAH LINE

which is a steamship company running passenger ships from Boston to New York (http://neveryetmelted.com/2014/10/17/great-london-beer-flood-of-1814/).

A contemporary report describes several fatalities; a woman and her daughter, the latter carried "through a partition" and "dashed to pieces"; a female servant in the local Tavistock Arms pub suffocated. The names given are Ann Saville, about 35 years old; Eleanor Cooper, between 15 and 16 years old, servant to Mr Hawse at the Tavistock Arms; Hannah Barnfield, four-and-a-half years old; Mrs Butler, her daughter, grand daughter, and three others, names unknown. Three brewery workers were rescued. One person was dug out alive, two brothers were severely injured. Several people were reported missing (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horse_Shoe_Brewery, Dreadful Accident (9345), The Times, hosted at infotrac.galegroup.com, 19 October 1814, p. 3).

Morning Chronicle – Thursday 20 October 1814

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000082/18141020/010/0003

The incident, in the area now occupied by the Dominion Theatre, caught the attention of the media nationwide. The Morning Chronicle documents that when one witness heard the vat crashing, he entered the storeroom and was instantly ‘up to his knees in beer’ and found that one side of the house and ‘a considerable part of the roof lay in ruins’.

Debra Chatfield, spokesperson for The British Newspaper Archive, said: “Some people would say that there are worse ways to die than drowning in freshly-brewed beer, but for the people in 19th century London, I’m sure it was terrifying.

“The beer-flood is one of many historical gems to be unearthed from the British Newspaper Archives’ unparalleled newspaper collection, which will have 40 million newspaper pages digitised over the next 10 years. It is a hugely important project and the magnitude of what we are working to achieve reinforces the importance of the media in documenting human history.” (http://blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2012/10/26/great-flood-of-london-eight-people-killed-as-wave-of-beer-swept-through-londons-streets/)

From a Dr Who cartoon novel in 2012: was the Great Beer Flood caused by time-travellers?

(No, obviously not …) (http://zythophile.co.uk/2014/10/17/remembering-the-victims-of-the-great-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-today/)

Late on the Monday afternoon of October 17, 1814, distraught Anne Saville mourned over the body of her 2-year-old son, John, who had died the previous day. In her cellar apartment in London’s St. Giles neighborhood, fellow Irishwomen offered comfort as they waked the small boy and awaited the arrival of their husbands and sons who toiled in grueling manual labor jobs around the city. Upstairs on the first floor of the cramped New Street tenement, Mary Banfield sat down for tea with her 4-year-old daughter, Hannah. Behind the Tavistock Arms public house on nearby Great Russell Street, 14-year-old servant Eleanor Cooper scoured pots at the outdoor water pump in the shadow of a 25-foot-high brick wall.

On the other side of the soaring barrier stood the extensive Bainbridge Street brewery of Messrs. Henry Meux and Co., which dominated the Irish enclave (www.history.com/news/the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago) (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

At the time of the disaster the Horse Shoe brewery had been in the hands of Henry Meux for just five years. The brewery’s origins are obscure: in the 20th century, at least, Meux & Co claimed a foundation date of 1764. Printed sources for its history are hit-and-miss. Richmond and Turton’s The Brewing Industry: a Guide to Historical Records, which is not always a reliable witness, asserts that it was “founded prior to 1764, after which date it was run by Blackburn and Bywell”. The Victorian History of the County of Middlesex wrote that it was “founded by a Mr Blackburn”, while Old and New London by Edward Walford, published in 1891, says that the brewery “was founded early in the reign of George III by Messrs Blackburn and Bywell whose name it bore until Mr Henry Meux, at that time a partner in the brewery of Messrs Meux in Liquorpond Street, joined the firm” (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

By 1792 the brewery was in the hands of John Stephenson. He was the “natural” son of another John Stephenson, a wealthy London merchant, originally from Cumberland. John Stephenson senior, whose uncle was at one time Lord Mayor of London, was an MP for more than 30 years from 1761 until his death at his home in Bedford Square in April 1794, aged 84. Stephenson senior was unmarried, and left almost all his estate, which included land in Cumbria, to his son. John junior, his wife Susan and their six or seven children moved after John senior’s death from nearby Charlotte Street into the rather finer house in Bedford Square, which was itself only a short walk north from the brewery. (Many of the streets and squares, and indeed pubs, in the area, incidentally, took their names from the local landowners, the Russell family, Dukes of Bedford and Marquesses of Tavistock, whose arms bore a red lion.)

Tragically, John junior had little time to enjoy his extra wealth. Like other breweries at the time, the Horse Shoe brewery cooled the hopped wort after it was boiled by pumping it into large, shallow vessels at the top of the building, before it was run into the fermenting vessels and pitched with yeast. Around 10am on the morning of Thursday, November 13, 1794, one of the brewery workers spotted a hat swimming on top of the beer in one of the coolers. It was Stephenson’s. Just a short time before he had been in the brewery “accompting house”. Unnoticed, he had gone up to where the coolers were, fallen in and drowned (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

....some time towards the end of 1809, the Horse Shoe brewery was bought by Henry Meux, who had been a partner in one of the largest of London’s porter brewers, Meux Reid. His father, Richard Meux (pronounced mewks), who came from an old landed family on the Isle of Wight, had been born in or just before 1734 (he was christened at the other St Giles, in Cripplegate, on the edge of the City). In 1757 Richard had gone into business, aged only 23 or so, as a partner in a brewery in Long Acre, Covent Garden. That brewery was badly damaged by fire in 1763, and Meux and his partner built a new one in Liquorpond Street, Clerkenwell, which they called the Griffin brewery, after the crest of Gray’s Inn nearby. The Griffin brewery was one of the first to go in for building absolutely enormous vats for maturing porter (ageing at least some of the porter sent to publicans was regarded, from at least the 1730s, as essential to achieve the flavour customers sought). In 1790 one vat was unveiled in Liquorpond Street that stood 20 feet high and 60 feet across: more than 200 people sat down to a dinner inside. Five years later Richard Meux was constructing another vat at the Griffin brewery, the “XYZ”, with a capacity of 20,000 barrels, at a cost of £10,000, equivalent to more than £750,000 today....The Griffin brewery’s success – it was the fifth largest in London in 1796, with production of just under 104,000 barrels – attracted rich new partners. These included a distiller and wine and spirit merchant called Andrew Reid, in 1793 (whereupon the brewery became known as Meux Reid), and, in 1798, Sir Robert Wigram, East India merchant, ship builder and owner of Blackwall docks on the Thames. Their capital helped the brewery acquire more pubs (it controlled more than 100 licensed houses in 1795) and extend more loans to publicans to increase their share in the furiously competitive London porter market.

In 1800 Richard Meux retired from the business. leaving the management of the Griffin brewery to his sons Richard junior, Henry and Thomas. Richard junior, was declared insane in 1806 (something that was also to happen to Henry Meux’s son decades later). Henry, the second eldest, and Thomas, the third, carried on, Thomas in charge of brewing, Henry looking after sales and tied houses. Unfortunately Henry became heavily involved with an extremely dodgy character called James Deady, one of the brewery’s two “abroad coopers”, or outside reps. Dodgy Deady’s tricks included seducing the wife of a free trade publican, and then having the publican jailed for failing to pay his bills to the brewery. Worse, as far as the company was concerned, Deady and Henry Meux were secretly running a distillery, a rival operation to the one owned by Andrew Reid. Eventually Reid found out, and in 1808 he launched a Court of Chancery case against Henry Meux, claiming that Meux had misappropriated £163,000 of the brewery’s capital.

The Court of Chancery judgment gave an option for the Meuxes to be bought out of the partnership, and in 1809 the Griffin brewery was put up for sale and purchased by members of the Reid and Wigram families, with the Meuxes getting a fifth of the proceeds. Thomas Meux remained one of 20 members of the new partnership (he eventually left in 1816, when the brewery became known simply as Reid & Co)....Henry Meux does seem to have taken with him a number of the Griffin brewery’s employees, including James Deady, when he and several partners acquired the Horse Shoe Brewery.

Under Henry Meux the Horse Shoe Brewery’s production absolutely rocketed, from 40,663 barrels in 1809 to 93,660 in 1810 and 103,502 barrels in 1811 (though this was still less than half that of Meux Reid’s 220,094 barrels, and far behind Barclay Perkins’s 264,105 barrels in 1811, the huge rise pushed the Horseshoe Brewery up from 10th to sixth place in the London porter brewery league table.) In 1813 or 1814 the Horse Shoe brewery acquired or merged with a smaller concern, Clowes & Co of the Stoney Lane brewhouse in Bermondsey. Then came the disaster

(http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

The Horse Shoe Brewery was an English brewery located in central London. It was established in 1764 and became a major producer of porter. It was the site of the London Beer Flood in 1814, which killed eight people after a porter vat burst. The brewery was closed in 1921.

The brewery tap, the Horseshoe, was established in 1623, and was named after the shape of its first dining room. The brewery was named after the tavern. The Horse Shoe Brewery was established in 1764 on the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street. By at least 1785 it was owned by Thomas Fassett. By 1786-7, it had the eleventh largest output of porter of any London brewery, producing 40,279 barrels a year.

By 1792 the brewery was owned by John Stephenson the younger, son of John Stephenson the elder. In 1794, after Stephenson's early death, the brewery ownership passed to Edward Biley. Biley ran the brewery until January 1809 when he was joined in partnership by John Blackburn and Edward Gale Bolero. Towards the end of 1809 the brewery was acquired by Henry Meux, who had been a partner in one of the largest of London’s porter brewers, Meux Reid of the Griffin Brewery in Clerkenwell. The company traded under the name Henry Meux & Co. The horseshoe became part of the Meux identity and was incorporated into their logo. By 1811 annual production had reached 103,502 barrels, making it the sixth largest brewer of porter in London. In 1813/14 the Horse Shoe brewery merged with or acquired Clowes & Co of Bermondsey (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horse_Shoe_Brewery).

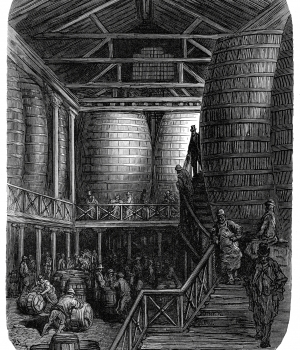

Engraving showing interior of 19th century London brewery.

(Credit: duncan1890/iStockphotos.com)

Founded early in the reign of King George III and famous for its porter, the brewery produced more than 100,000 barrels of the dark-colored nectar each year.

Around 4:30 p.m., storehouse clerk George Crick inspected one of the three-story-tall wooden vats girdled with heavy iron hoops in which the black beer fermented. As he looked down from his perch, the clerk suddenly noticed that a 700-pound hoop had slipped off an enormous cask that stored a 10-month-old batch of porter. Crick, who had been with the company for 17 years and watched it grow to become the city’s fifth-largest producer of porter, knew that this happened two or three times a year and didn’t think much of it. Even though porter filled all but the final 4 inches of the 22-foot-high vat and the pressure from the fermentation process was building inside, Crick’s boss told him “that no harm whatever would ensue” from the broken hoop and that he should write a letter to another brewery employee who could fix it at a later date (www.history.com/news/the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago).

The first hint of what was going to happen occurred at around half past four in the afternoon of Monday October 17 1814, when a seven-hundredweight iron hoop, the smallest of 22 securing a 22-feet-high vat in the storehouse at the back of the brewery, and about three feet from the bottom of the vat, fell off. The vat was filled within four inches of the top with 3,555 barrels of “entire”, porter already 10 months old and destined to be sent out when judged properly mature to be mixed with freshly brewed porter to customers’ tastes, in Meux’s pubs. George Crick, the storehouse clerk, who was on duty at the time, told the inquest held into the deaths of the victims of the disaster that he was “not alarmed” at the hoop falling off as it happened “frequently”, two or three times a year, and was “not attended by any serious consequence”. Nevertheless, Crick said, he wrote a note to Florance Young, one of the brewery partners, who ran a back-making (that is, brewery vessel making) business, to let him know what had happened, so that someone would come to mend the hoop (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

Soon after he penned the note around 5:30 p.m., Crick heard a massive explosion from inside the storeroom. The compromised vat, which held the equivalent of 1 million pints of beer, had burst into splinters. The blast broke off the valve of an adjoining cask that also contained thousands of barrels of beer and set off a chain reaction as the weight of the 570 tons of liquid smashed other hogsheads of porter (www.history.com/news/the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago).

At 5.30pm Crick was standing just a short distance from the vat in question, with the note for Young in his hand, when he heard the vat burst. He ran to the storehouse where the vat was, and was shocked to see that the end wall, at least 25 feet high, 60 feet long and 22 inches thick at its broadest part, together with a large part of the roof, lay in ruins. The force of the escaping beer, and flying debris, including the huge staves of the collapsing vat, smashed several hogsheads of porter in the storehouse and knocked the cock out of another large vat in the cellar below which contained 2,100 barrels of beer, all of which except 800 or 900 barrels joined the flood (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

Crick and his colleagues, now up to their waists in porter, were too busy rescuing their fellow workers injured as the vat collapsed, and trying to save as much beer as possible, to pay attention to what had happened outside. The vast flood of escaping porter, weighing hundreds of tons, had crashed down New Street behind the brewery and smashed into the buildings there and fronting Great Russell Street to the north. By good fortune the tenements in and around New Street, all in multiple occupation, were comparatively empty, because of the time of day. Had the accident happened an hour or more later, the men would have been home from work and the death toll greater. Instead all those killed were women and children (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

I said ... correctly, that the vat of porter which burst suddenly on Monday October 17, 1814 at Henry Meux’s Horse Shoe Brewery contained 3,550 barrels of beer. I said, correctly, that this amounted to more than a million pints. Then for some mad brain-burp reason I said the beer in the vat weighed “around 38 tons” – almost precisely 15 times less than the correct answer, which was actually more than 571 tons (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

On Thursday a Coroner’s Inquest was held on the dead bodies at St Giles’s workhouse. George Crick deposed that he was store house clerk to Messrs H Meux and Co of the Horse Shoe Brew house in St Giles’s, with whom he had lived 17 years. Monday afternoon one of the large iron hoops of the vat which burst fell off. He was not alarmed, as it happened frequently and was not attended by any serious consequence. He wrote to inform a partner, Mr Young, also a vat builder, of the accident, he had the letter in his hand to send to Mr Young, about half past five, half an hour after the accident, and was standing on a platform within three yards of the vat when he heard it burst. He ran to the store house where the vat, was and was shocked to see that one side of the brew house, upwards of 25 feet in height and two bricks and a half thick, with a considerable part of the roof, lay in ruins. The next object that took his attention was his brother, J Crick, who was a superintendent under him, lying senseless, he being pulled from under one of the butts. He and the labourer were now in the Middlesex Hospital. An hour after, witness found the body of Ann Saville floating among the butts, and also part of a private still, both of which floated from neighbouring houses. The cellar and two deep wells in it were full of beer, which witness and those about him endeavoured to save, so that they could not go to see the accident, which happened outwardly. The height of the vat that burst was 22 feet; it was filled within 4 inches of the top and then contained 3555 barrels of entire, being beer that was ten months brewed; the four inches would hold between 30 and 40 barrels more; the hoop which burst was 700 cwt, which was the least weight of any of 22 hoops on the vat. There were seven large hoops, each of which weighed near a ton. When the vat burst the force and pressure was so great that it stove several hogsheads of porter and also knocked the cock out of a vat nearly as large that was in the cellar or regions below; this vat contained 2100 barrels all of which except 800 barrel also ran; about they lost in all between 8 and 9000 barrels of beer; the vat from whence the cock was knocked out ran about a barrel a minute; the vat that burst had been built between eight and nine years and was kept always nearly full. It had an opening on the top about a yard square; it was about eight inches from the wall; witness supposes it was the rivets of the hoops that slipped, none of the hoops being broke and the foundation where the vat stood not giving way. The beer was old, so that the accident could not have been occasioned by the fermentation, that natural process being past; besides, the action would then have been upwards and thrown off the flap made moveable for that purpose (http://zythophile.co.uk/2014/10/17/remembering-the-victims-of-the-great-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-today/).

The force of the explosion sent bricks raining over the tops of houses on Great Russell Street and collapsed the brick wall that towered over Eleanor Cooper, killing her instantly. A torrent of porter rushed through the narrow lanes of the surrounding neighborhood and swept away everything in its path. With no drainage on the city streets, the wave of black liquid had nowhere to go except straight into the neighboring homes. Residents scaled tables and furniture to save themselves from drowning as the beer inundated the houses. Decrepit hovels flanking the brewery crumbled under the deluge (www.history.com/news/the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago).

(http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/)

The worst damage occurred on New Street. The cascade swept away Hannah and Mary Banfield in the middle of their tea, and the little girl drowned in the tsunami of beer. The force of the tidal wave then caused the house to collapse on the mourners huddled in the cellar, killing Anne Saville and four others (www.history.com/news/the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago).

The flood reached George Street and New Street within minutes, swamping them with a tide of alcohol. The 15 foot high wave of beer and debris inundated the basements of two houses, causing them to collapse. In one of the houses, Mary Banfield and her daughter Hannah were taking tea when the flood hit; both were killed.

In the basement of the other house, an Irish wake was being held for a 2 year old boy who had died the previous day. The four mourners were all killed. The wave also took out the wall of the Tavistock Arms pub, trapping the teenage barmaid Eleanor Cooper in the rubble. In all, eight people were killed. Three brewery workers were rescued from the waist-high flood and another was pulled alive from the rubble (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-London-Beer-Flood-of-1814/) (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

Soaked in poverty, the St. Giles neighborhood was now saturated in beer. Rescuers, their clothes drenched in hot malt liquor, waded through the waist-high flood of beer and picked through the tangle of bricks and wood with their hands in search of those trapped inside. They tried to silence the gawkers and frantic family members in order to hear the faint cries and groans emanating from the ruins. “The surrounding scene of desolation presents a most awful and terrific appearance, equal to that which fire or earthquake may be supposed to occasion,” reported London’s Morning Post. Although on the surface the London Beer Flood may sound whimsical, similar to the molasses flood that struck Boston in 1919, the suffering was palpable. The Morning Post reported at the time that is was “one of the most melancholy accidents we ever remember.” While all inside the brewery survived, the London Beer Flood claimed the lives of eight women and children.

The five dead mourners who gathered at John Saville’s wake were waked themselves at the Ship public house down Bainbridge Street from the brewery. Anne Saville now joined her son in a coffin next to those of Elizabeth Smith, Catherine Butler, Mary Mulvey and her 3-year-old son, Thomas Murray. The shrouded coffins of Eleanor Cooper, Hannah Banfield and 3-year-old Sarah Bates were laid out in a nearby yard as a stream of Londoners paid their respects and clinked pennies and shillings onto a plate to pay for their funerals (www.history.com/news/the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago).

All this ‘free’ beer led to hundreds of people scooping up the liquid in whatever containers they could. Some resorted to just drinking it, leading to reports of the death of a ninth victim some days later from alcoholic poisoning (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-London-Beer-Flood-of-1814/). After the accident, watchmen charged people a penny or two-pence to see the ruins of the beer vats, and visitors came in their hundreds to witness the macabre spectacle. But a report in The Times praised local people’s response to the disaster, noting how the crowd kept quiet so the cries of trapped victims could be heard.

In fact, it seems like later rumours that people collected the beer in pots and pans were untrue, as Martyn Cornell, author of Amber, Gold and Black: The History of Britain’s Great Beers, explains: “None of the London newspapers report anyone trying to drink the beer after the flood, indeed, they say the crowds that gathered were pretty well behaved. Only much later did stories start being told about riots, people getting drunk and so on: these seem to have been be prompted by what people thought ought to have happened, rather than what did happen.” (www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/what-really-happened-in-the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-9796096.html).

Accounts today of the Meux brewery beer flood are full of claims of “besotted mobs flinging themselves into gutters full of beer, hampering rescue efforts” and claims that “many were suffocated in the crush of hundreds trying to get a free beer” and “the death toll eventually reached 20, including some deaths from alcohol coma”. None of this is borne out by any newspaper reports at the time, and nor are the stories about riots at the Middlesex Hospital when victims were taken there stinking of beer, because other patients smelt the porter and thought free drink was being given away, or the floor at the pub where several of the victims’ bodies were laid out collapsing under the weight of sightseers and more people being killed. All those stories appear to be completely made up. It would be an interesting exercise to track these myths back and see when and where they first arose (http://zythophile.co.uk/2014/10/17/remembering-the-victims-of-the-great-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-today/).

Similarly there’s a myth arisen that when those injured after the vat burst were taken to the nearby Middlesex Hospital, “patients already there for illnesses unrelated to the beer disaster smelled the ale and began a riot, accusing doctors and nurses of holding out on the beer they thought was being served elsewhere in the hospital”, while another myth claims that when bodies of those killed were taken “to a nearby house for identification”, so many people turned up to see them that “the floor collapsed under the sheer weight of onlookers” and “many inside the building perished in the collapse.” None of this is in any reports of the accident from newspapers in 1814, and if any of it had happened, you can bet one of them would have written about it (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

As far as I can discover, only the Bury and Norfolk Post, in its report of the tragedy nine days after the event, describes anyone drinking the escaped porter, claiming that “When the beer began to flow, the neighbourhood, consisting of the lower classes of the Irish, were busily employed in putting in their claim to a share, and every vessel, from a kettle to a cask, were put into requisition, and many of them were seen enjoying themselves at the expense of the proprietors.” None of the London papers, who would certainly not have been friends of the poor Irish, especially the Times, report anything like this. One wonders if the Post was describing what it expected to have happened (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

First reports estimated that between 20 and 30 people had died in the disaster. But at the coroner’s inquest, held in St Giles’s Workhouse on the Wednesday, two days later, the only victims, most of whom were not found until the next day, were revealed to be three small children, the teenaged Eleanor Cooper, three women aged 27 to 35, and the elderly Catharine Butler. George Crick was the first witness called, and he told the coroner his surmise was that the rivets on the hoops around the vat that burst had slipped, since none of the hoops had broken, nor had the foundations underneath the vat collapsed. Instead the whole vat “had given way as completely as if a quart pot had been turned up on the table.” His own brother, John, was one of two brewery workers still in the Middlesex Hospital “in a dangerous way” after being injured in the accident, Crick said. He also revealed that the body of Ann Saville had been found “floating among the butts” an hour after the vat collapsed, where she had evidently been washed. Parts of a private still was also found floating in the beer: it appeared that someone in New Street had been engaged in a little illegal gin-making. The coroner’s jury, after hearing the evidence and viewing the bodies, returned a verdict “without hesitation” of “died by casualty, accidentally and by misfortune” (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

‘The bursting of the brew-house walls, and the fall of heavy timber, materially contributed to aggravate the mischief, by forcing the roofs and walls of the adjoining houses.' The Times, 19th October 1814.

Some relatives exhibited the corpses of the victims for money. In one house, the macabre exhibition resulted in the collapse of the floor under the weight of all the visitors, plunging everyone waist-high into a beer-flooded cellar.

The stench of beer in the area persisted for months afterwards.

The brewery was taken to court over the accident but the disaster was ruled to be an Act of God, leaving no one responsible (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-London-Beer-Flood-of-1814/). All those who came to see the bodies were asked to make a small donation – sixpence or a shilling – towards the families of the survivors, with the collection at the Ship totalling £33 5s 7d. It was not much, against estimates that the poor victims of the flood had lost £3,000 in ruined belongings. A fund was set up for their relief by the churchwardens of the two parishes that covered the area hit by the disaster, St Giles’s, and St George, Bloomsbury, and within a month more than £800 had been raised, including £30 from Florance Young (whose family later owned Young’s brewery in Wandsworth) and £10 from John Vickris Taylor of the Limehouse brewery (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

Only two days after the catastrophe, a jury convened to investigate the accident. After visiting the site of the tragedy, viewing the bodies of the victims and hearing testimony from Crick and others, the jury rendered its verdict that the incident had been an “Act of God” and that the victims had met their deaths “casually, accidentally and by misfortune.” Not only did the brewery escape paying damages to the destitute victims, it received a waiver from the British Parliament for excise taxes it had already paid on the thousands of barrels of beer it lost (www.history.com/news/the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago).

The company found it difficult to cope with the financial implications of the disaster, with a significant loss of sales made worse because they had already paid duty on the beer. They made a successful application to Parliament reclaiming the duty which allowed them to continue trading (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Beer_Flood).

The flood cost the brewery around £23000 (approx. £1.25 million today). However the company were able to reclaim the excise duty paid on the beer, which saved them from bankruptcy. They were also granted ₤7,250 (₤400,000 today) as compensation for the barrels of lost beer (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-London-Beer-Flood-of-1814/).

An inquest heard that there had been an indication that the vat was unstable earlier in the afternoon of the 17th, when one of the metal hoops holding it together snapped. A jury cleared the brewers of any wrongdoing, considering the incident as an unavoidable act of God. Henry Meux & Co., the owners, received a refund for the excise duty they had paid to produce the beer they had lost.

However, one person, addressing himself only as a “friend of humanity” in a letter to the Morning Post newspaper, thought the accident should have been foreseen. “I have always held it as my firm opinion, that the many breweries and distilleries in this metropolis… are most dangerous establishments, and should not be permitted to stand in the heart of the town,” the correspondent wrote. “I am only surprised, when I consider the immense body contained in these ponderous vats, that similar accidents do not more frequently occur." (www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/what-really-happened-in-the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-9796096.html).

Bijzonder, dat zo'n vat, waarbij dus al een metalen band van was gesprongen, niet wordt gerepareerd of vervangen. En dat de overheid dat het bedrijf niet nalatig verklaard, maar het afschuift op 'intelligent design'. Als dat nu zou gebeuren bij Heineken of Grolsch zou het commentaar niet ophouden...

This unique disaster was responsible for the gradual phasing out of wooden fermentation casks to be replaced by lined concrete vats. The Horse Shoe Brewery was demolished in 1922; the Dominion Theatre now sits partly on its site (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-London-Beer-Flood-of-1814/).

Why did they store such huge quantities of porter at the brewery in such enormous vessels? Because experience had shown that porter stored for months in vats acquired a particularly sought-after set of flavours, and storing it in really big vessels reduced the risk of oxidisation (since the surface area merely squared as the volume cubed). This “stale” (meaning “stood for some time”, rather than “off”), flat and probably quite sour aged porter was then send out in casks when ready, and mixed at the time of service in the pub with porter from a cask that was “mild”, that is, fresh and still lively, and probably a little sweet. Customers would specify the degree of mildness or staleness they would like their porter drawn, having it mixed to their own preference. Tastes changed over the 19th century, “stale” porter fell out of favour, and by the 1890s the big vats were being dismantled, the oak they were made from recycled into pub bar-tops. Quite possibly there are pubs in London now whose bars are made out of old porter vats (http://zythophile.co.uk/2014/10/17/remembering-the-victims-of-the-great-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-today/).

On the 17 October 1814, corroded hoops on a large vat at the brewery prompted the sudden release of about 7,600 imperial barrels (270,000 imp gal) of porter. The resulting torrent caused severe damage to the brewery's walls and was powerful enough to cause several heavy wooden beams to collapse. The flood's severity was exacerbated by the landscape, which was generally flat. The brewery was located in a densely populated and tightly packed area of squalid housing (known as the rookery). Many of these houses had cellars. To save themselves from the rising tide of alcohol, some of the occupants were forced to climb on furniture. Several adjoining houses were severely damaged, and eight people killed. The accident cost the brewery about £23,000, although it petitioned Parliament for about £7,250 in Excise drawback, saving it from bankruptcy (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horse_Shoe_Brewery).

After the disaster, the brewery continued to be one of the largest producers of porter in London throughout the nineteenth century. Sir Henry Meux, 2nd Baronet took ownership of the company in 1841 following the death of his father. Production of ale began in 1872. Meux employed three partners to manage the brewery: Richard Berridge, Dudley Coutts Marjoribanks and William Arabin. In 1878, Henry Bruce Meux and Marjoribanks (now Lord Tweedmouth) took over management of the company, which they renamed Meux's Brewery Company Ltd when they registered it as a public company in 1888....The Horse Shoe Brewery closed in 1921. By this time the site covered 103,000 square feet (9,600 m2), but there was no available land to expand. Production was transferred to the Thorne Brothers' Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, which the company had bought in 1914. The Nine Elms brewery was renamed the Horse Shoe Brewery. The original Horse Shoe Brewery was demolished in 1922, and in 1928-9 the Dominion Theatre was erected on the site.

In 1956, Meux merged with Friary, Holroyd and Healy of Guildford to form Friary Meux. They went into liquidation in November 1961 and the company was acquired by Allied Breweries in 1964. The Horse Shoe Brewery ceased to brew in 1966. The Friary Meux brand was revived by Allied in 1979 as a name for a branch of their public houses, but disappeared after Allied's pubs were sold to Punch Taverns in 1999.

The former brewery tap is now a branch of Dorothy Perkins, but here are still traces of the Meux brand in London. Notable, until demolition in 2015, was the "Meux's Original London Stout" logo on the side of the derelict Sir George Robey public house in Seven Sisters Road near Finsbury Park station. This was familiar to large numbers of Arsenal football supporters who passed it on their way to home matches at the Emirates Stadium (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Beer_Flood).

The Horse Shoe Brewery soon went back into production, only closing in 1921, when it was replaced by the Dominion Theatre (www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/what-really-happened-in-the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-9796096.html).

In 1921 the Horse Shoe Brewery, which was increasingly an anachronism as a large brewery in the heart of London, finally closed, with production transferred to Thorne Brothers’ Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, which Meux had bought in 1914. (The brewery was demolished in 1922, and in 1927-28 the Dominion Theatre was erected on the site.) In 1956 Meux merged with Friary Holroyd and Healey of Guildford to form Friary Meux. Eight years later, in 1964, Friary Meux was snapped up by the fast-expanding Allied Breweries. Like Taylor Walker, the name was revived by Allied in 1979 as a disguise for one of its pub-owning subsidiaries, but vanished again when Allied sold its pubs to Punch 20 years later (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

The terrible scene that unfolded there two hundred years ago has been largely forgotten, although a local pub - The Holborn Whippet – brews a special anniversary ale each year (www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/what-really-happened-in-the-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-9796096.html). In 2012, a local tavern, the "Holborn Whippet", has started to mark this event with a vat of porter brewed especially for the day (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Beer_Flood).

The Horse Shoe brewery maintained its position as one of London’s leading porter producers for the rest of the 19th century: indeed, it was the last one to remain solely a porter brewer, with production of ale not being introduced until 1872 (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

The brewery has been demolished, and the Dominion Theater now stands in its place. While there is no plaque or memorial to signify the beer flood, a local tavern, the Holborn Whippet, serves a special porter that commemorates the beer flood once a year, on the anniversary of the event.

Tottenham Court Road , England, W1T 7AQ, United Kingdom

(www.atlasobscura.com/places/site-london-beer-flood).

At the Brewery History Society we have been trying to get a plaque put up to commemorate the event, and honour the victims, but with no success: ...the Camden Historical Society, inside whose borough the site now falls, took the strange view that “not enough people died” to make it worthwhile having a permanent memorial. How many dead women and children is enough, Camden?

...

Wherever you are at 5.30pm this evening, please stop a moment and raise a thought – a glass, too, if you have one, preferably of porter – to Hannah Banfield, aged four years and four months; Eleanor Cooper, 14, a pub servant; Elizabeth Smith, 27, the wife of a bricklayer; Mary Mulvey, 30, and her son by a previous marriage, Thomas Murry (sic), aged three; Sarah Bates, aged three years and five months; Ann Saville, 60; and Catharine Butler, a widow aged 65. All eight died .., victims of the Great London Beer Flood, when a huge vat filled with maturing porter fell apart at Henry Meux’s Horse Shoe brewery at the bottom of Tottenham Court Road, and more than 570 tons of beer crashed through the brewery’s back wall and out into the slums behind in a vast wave at least 15 feet high, flooding streets and cellars and smashing into buildings, in at least one case knocking people from a first-floor room. It could have been worse: the vat that broke was actually one of the smallest of 70 or so at the brewery, and contained just under 3,600 barrels of beer, while the largest vat at the brewery held 18,000 barrels. In addition, if the vat had burst an hour or so later, the men of the district would have been home from work, and the buildings behind the brewery, all in multiple occupancy, with one family to a room, would have been much fuller when the tsunami of porter hit them (http://neveryetmelted.com/2014/10/17/great-london-beer-flood-of-1814/) (http://zythophile.co.uk/2014/10/17/remembering-the-victims-of-the-great-london-beer-flood-200-years-ago-today/).

The vat that burst, in spite of all the death and destruction it caused, was not actually the largest at the brewery: indeed, this report from a visit to the Horse Shoe Brewery in 1812, two years before the disaster, written by a 34-year-old Orkney-born novelist called Mrs Mary Brunton, suggests it was one of the smallest (http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/).

Dus, een bizarre ramp, door onvoorzichtigheid of nalatigheid? Waarbij gelukkig niet veel doden zijn te betreuren, maar desondanks zijn er 8 slachtoffers te betreuren. Opmerkelijk dat de brouwerij wel werd gecompenseerd, maar er niks over de arme slachtoffers wordt vermeld. Daar was een inzameling voor nodig en daarbij wordt zelfs een connotatie van ongepaste gierigheid. Vreemd... Een vreemd ongeluk. Een vreemde anekdote in de de biergeschiedenis...