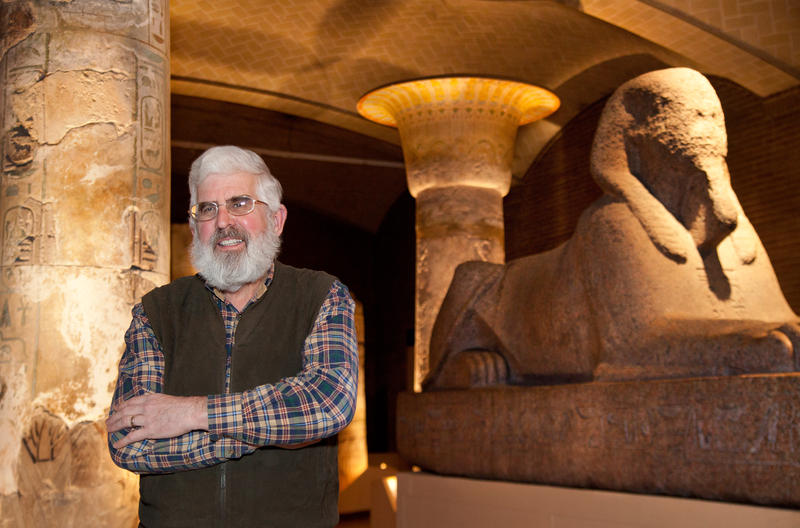

Patrick McGovern, a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia (www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology/).

(www.archaeological.org/lecturer/patrickemcgovern) (http://penn.museum/press-releases/164-5100-year-old-chemical-evidence-for-ancient-medicinal-remedies-discovered-in-ancient-egyptian-wine-jars.html).

Patrick Edward McGovern (born December 9, 1944) is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, where he is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology. In the popular imagination, he is known as the "Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages"[1] ... McGovern is well known for his book on Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton University, 2003/2006),[16] which received the Grand-Prix in Histoire, Littérature et Beaux-arts from the International Organisation of Vine and Wine plus two other awards.

His most recent book, Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages (Berkeley: University of California),[17] received an award from the Archaeological Institute of America.

In addition to over 150 periodical articles, he has written or edited another eight books, including The Origins and Ancient History of Wine (Gordon and Breach, 1996),[18](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Edward_McGovern) Zie ook https://www.sas.upenn.edu/anthropology/people/patrick-mcgovern.

Patrick McGovern is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, where he is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology. In the popular imagination, he is known as the

"Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages." (www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology/)

With his bushy white beard and jovial manner, Patrick McGovern '66 seems more like Santa than the "Indiana Jones of ancient ales, wines and extreme beverages."

McGovern, who studied chemistry as a Cornell undergraduate, has chemically identified the world's oldest known grape wine, from Hajji Firuz, Iran, circa 5400 B.C., and the oldest barley beer, also from Iran, circa 3400 B.C.

A pioneer in biomolecular archaeology who is now a scientific director of a laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, McGovern combines his scientific acumen and advanced anthropological studies with an interest in winemaking and viticulture that originated when he was a teenager in Ithaca. He is the author of two books on the subject: "Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer and Other Alcoholic Beverages" and "Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture." (http://ezramagazine.cornell.edu/Update/May12/EU.McGovern.uncorks.html) Zei ook https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520267985/uncorking-the-past

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology is dedicated to the study and understanding of human history and diversity. Founded in 1887, the Museum has sent more than 400 archaeological and anthropological expeditions to all the inhabited continents of the world. The Museum is located at 3260 South Street (across from Franklin Field), Philadelphia, PA 19104, and on the web at www.penn.museum ... Penn Medicine is one of the world’s leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (founded in 1765 as the nation’s first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $3.6 billion enterprise. Penn’s School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report’s survey of research-oriented medical schools (www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology1/). (http://penn.museum/press-releases/164-5100-year-old-chemical-evidence-for-ancient-medicinal-remedies-discovered-in-ancient-egyptian-wine-jars.html)

Dr. Patrick E. McGovern is the kind of Scholar writers and researchers make pilgrimages to, on his time schedule—not necessarily receive visits from, when they just happen to be in town.

Nevertheless, and in spite of the fact that the globe-trotting scientist was recovering from jet lag after concluding a stint of recent fieldwork in China, we were overjoyed to spend some time with Dr. McGovern (www.thecomicbookstoryofbeer.com/with-dr-patrick-e-mcgovern/).

His academic background combined the physical sciences, archaeology, and history–an A.B. in Chemistry from Cornell University, graduate work in neurochemistry at the University of Rochester, and a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Archaeology and Literature from the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department of the University of Pennsylvania.

Over the course of his more than three decade career at the Penn Museum, his laboratory has been at the cutting-edge of applying new scientific techniques to archaeology, often referred to as archaeometry or archaeological science. ... In the early 1990s, the laboratory identified the earliest chemically confirmed instances of grape wine and barley beer from the Near East, viz., from Godin Tepe in Iran, ca. 3400-3000 B.C.[6] Several years later, the earliest date for wine was pushed back another two millennia to the Neolithic period (ca. 5400-5000 B.C.), based on analyses of jars from the Museum's excavation at Hajji Firuz in Iran.[7] In a paper published 2017 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of historians and scientists explicated the biomolecular archaeological and archaeobotanical evidence for a further backdating to 6000–5800 B.C.[8]. DNA studies of grape has shown that the Eurasian grape (Vitis vinifera) was probably domesticated in the mountainous Near East, in the region extending from the northwestern Zagros Mountains to Transcaucasia to the eastern Taurus Mountains, as early as 7000 B.C.[9] These investigations led to the Eurasian grape being chosen as the first fruit to have its genome fully sequenced.

Research at the start of the new millennium focused on the Neolithic period of ancient China's Yellow River valley. At the site of Jiahu, the laboratory discovered the earliest alcoholic beverage in the world dating back to about ca. 7000-6600 B.C.[10] It was a mixed fermented beverage of rice, honey, and grape and/or hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida and C. cuneata) fruit. ...

In the late 1990s, the laboratory and collaborators analyzed the extraordinarily well-preserved organic residues inside the largest known Iron Age drinking-set, excavated inside the burial chamber of the Midas Tumulus at Gordion in Turkey, ca. 740-700 B.C.[15] The reconstruction of the "funerary feast"–which paired a mixed or extreme fermented beverage of grapes, barley and honey, viz. wine, beer and mead ("Midas Touch," see below) with a spicy, barbecued lamb and lentil stew–is the first time that an ancient meal has been re-created based solely on the chemical evidence.

The gala re-creation of the feast was at the Penn Museum in 2000; other dinners have been held in California, Michigan, and Washington, D.C. A re-creation at the tomb itself was filmed for a Channel 4 special in Britain–the beverage, made by the Kavaklidere winery, was served in and drunk from re-created vessels, and local villagers from Polatli prepared the stew by grinding the lentils in basalt mortars and barbecued the meat on open-fire spits.

McGovern took his scientific study of ancient alcoholic beverages one step further by re-creating them, both to learn more about how ancient humans accomplished what they did and to bring the past alive. His collaboration with Dogfish Head Brewery led to the commercial version of Midas Touch, the brewery's most awarded brew in major tasting competitions, Chateau Jiahu (based on the earliest alcoholic beverage from China), and Theobroma (an interpretation of the ancient cacao beverage and named after the tree). Maize or corn chicha was a non-commercial experiment, following traditions of the ancient Inca empire, in which native Peruvian red maize was chewed to break the carbohydrates down into sugars; pepperberries and strawberries were also added. A re-creation of an ancient Egyptian brew (Ta-Henket = ancient Egyptian "bread-beer"), which is based on archaeobotanical and Biomolecular Archaeological evidence dating between ca. 16,000 and 3150 B.C., was released in early December 2011.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Edward_McGovern)

For anyone intrigued by the intersection of beer, history, and science, familiarity with Dr. McGovern’s work should be considered crucial. He is the (big inhale) Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia (exhale…if you have anything left). And he and his colleagues are responsible for unearthing some of the most ancient beers and wines yet discovered by modern human beings. Moreover, he is an author of several books and a collaborator on an award-winning series of Ancient Ales, historical beers and ales brewed and distributed by Dogfish Head (www.thecomicbookstoryofbeer.com/with-dr-patrick-e-mcgovern/).

Fermented beverages have been preferred over water throughout the ages: they are safer, provide psychotropic effects, and are more nutritious. Some have even said alcohol was the primary agent for the development of Western civilization, since more healthy individuals (even if inebriated much of the time) lived longer and had greater reproductive success. When humans became "civilized," fermented beverages were right at the top of the list for other reasons as well: conspicuous display (the earliest Neolithic wine, which might be dubbed "Chateau Hajji Firuz," was like showing off a bottle of Pétrus today); a social lubricant (early cities were even more congested than those of today); economy (the grapevine and wine tend to take over cultures, whether Greece, Italy, Spain, or California); trade and cross-cultural interactions (special wine-drinking ceremonies and drinking vessels set the stage for the broader exchange of ideas and technologies between cultures); and religion (wine is right at the center of Christianity and Judaism; Islam also had its "Bacchic" poets like Omar Khayyam).

Whatever the reason, we continue to live out our past civilization by drinking wine made from a plant that has its origins in the ancient Near East. Your next bottle may not be a 7000 year old vintage from Hajji Firuz, but the grape remains ever popular—cloned over and over again from those ancient beginnings (www.penn.museum/sites/wine/wineintro.html).

It is well known that the French did not invent wine - no more than the Colombians invented coffee or the Italians discovered tomatoes - but they elevated it to a high art.

Now, after analyzing residue from a hunk of ancient limestone, a University of Pennsylvania scientist said Monday that he had found the earliest chemical evidence of le vin français (http://articles.philly.com/2013-06-05/news/39743409_1_vessels-wine-culture-french-wine).

Dr. Patrick E. McGovern is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. He is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology. His academic background combined the physical sciences, archaeology, and history–an A.B. in Chemistry from Cornell University, graduate work in neurochemistry at the University of Rochester, and a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Archaeology and Literature from the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department of the University of Pennsylvania.

Over the past two decades, he has pioneered the emerging field of Molecular Archaeology. In addition to being engaged in a wide range of other archaeological chemical studies, including radiocarbon dating, cesium magnetometer surveying, colorant analysis of ancient glasses and pottery technology, his endeavors of late have focused on the organic analysis of vessel contents and dyes, particularly Royal Purple, wine, and beer. The chemical confirmation of the earliest instances of these organics–Royal Purple dating to ca. 1300-1200 B.C. and wine and beer dating to ca. 3500-3100B.C.–received wide media coverage. A 1996 article published in Nature, the international scientific journal, pushed the earliest date for wine back another 2000 years–to the Neolithic period (ca. 5400-5000B.C.).

His research–showing what Molecular Archaeology is capable of achieving—has involved reconstructing the “King Midas funerary feast” (Nature 402, Dec. 23, 1999: 863-64) and chemically confirming the earliest fermented beverage from anywhere in the world—Neolithic China, some 9000 years ago, where pottery jars were shown to contain a mixed drink of rice, honey, and grape/hawthorn tree fruit (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 101.51: 17593-98). Most recently, he and colleagues identified the earliest beverage made from cacao (chocolate) from a site in Honduras, dated to ca. 1150 B.C., and an herbal wine from Dynasty 0 in Egypt.

He is the author of Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton University Press, 2003), and most recently, Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages (Berkeley: University of California, 2009). In addition to over 100 periodical articles, McGovern has also written or edited 10 books, including The Origins and Ancient History of Wine (Gordon and Breach, 1996), Organic Contents of Ancient Vessels (MASCA, 1990), Cross-Craft and Cross-Cultural Interactions in Ceramics (American Ceramic Society, 1989), and Late Bronze Palestinian Pendants: Innovation in a Cosmopolitan Age (Sheffield, 1985). In 2000, his book on the Foreign Relations of the “Hyksos,” a scientific study of Middle Bronze pottery in the Eastern Mediterranean, was published by Archaeopress.

As a Research Associate in the Near East Section of the Museum, he has also directed the Baq`ah Valley (Jordan) Project over the past 25 years (described in a University Museum monograph, The Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Central Transjordan, 1986), and been involved with many other excavations throughout the Middle East as a pottery and stratigraphic consultant. A detailed study of the New Kingdom Egyptian garrison at Beth Shan, an older Museum excavation, also appeared in 1994 in the Museum Monograph series, entitled The Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan.

As an Adjunct Professor in the Anthropology Dept. at Penn, he teaches courses on Molecular Archaeology (http://www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology/?page_id=10).

The earliest known chemical evidence of beer dates to circa 3500–3100 BC from the site of Godin Tepe in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran (www.inebriatedwisdom.com/beer-trivia-of-the-day-1-6-16-earliest-beer/).

McGovern can’t simply look for the presence of alcohol, which survives barely a few months, let alone millennia, before evaporating or turning to vinegar. Instead, he pursues what are known as fingerprint compounds. For instance, traces of beeswax hydrocarbons indicate honeyed drinks; calcium oxalate, a bitter, whitish byproduct of brewed barley also known as beer stone, means barley beer.

Tree resin is a strong but not surefire indicator of wine, because vintners of old often added resin as a preservative, lending the beverage a pleasing lemony flavor (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=3).

Archaeology is, at heart, a destructive science, McGovern recently told an audience at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian: “Every time you excavate, you destroy.” (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=6)

Dr. Patrick E. McGovern is Senior Research Scientist with the Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology (MASCA) and Adjunct Associate Professor with the Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Museum. He received his degrees from Cornell University (A.B. in Chemistry) and the University of Pennsylvania (Ph.D. in Near Eastern Archaeology and History). His areas of specialization include biomolecular Archaeology, the archaeology of the Near East and Egypt (particularly Bronze Age), ancient DNA, organic contents analysis, pottery provenancing, and technological innovation and cultural change. He has published ten books and over 100 articles, his most recent work is “Uncorking the Past: The Human Quest for Alcoholic Beverages” (2009, University of California) (http://aia.archaeological.org/webinfo.php?page=10224&lid=202).

Once the boiling brown pottery mixture cooks down to a powder, says Gretchen Hall, a researcher collaborating with McGovern, they’ll run the sample through an infrared spectrometer. That will produce a distinctive visual pattern based on how its multiple chemical constituents absorb and reflect light. They’ll compare the results against the profile for tartaric acid. If there’s a match or a near-match, they may do other preliminary checks, like the Feigl spot test, in which the sample is mixed with sulfuric acid and a phenol derivative: if the resulting compound glows green under ultraviolet light, it most likely contains tartaric acid. So far, the French samples look promising.

McGovern already sent some material to Armen Mirzoian, a scientist at the federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, whose primary job is verifying the contents of alcoholic beverages—that, say, the gold flakes in the Italian-made Goldschlager schnapps are really gold. (They are.) His Beltsville, Maryland, lab is crowded with oddities such as a confiscated bottle of a distilled South Asian rice drink full of preserved cobras and vodka packaged in a container that looks like a set of Russian nesting dolls. He treats McGovern’s samples with reverence, handling the dusty box like a prized Bordeaux. “It’s almost eerie,” he whispers, fingering the bagged sherds inside. “Some of these are 5,000, 6,000 years old.” (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=3).

By analyzing ancient pottery, Patrick McGovern is resurrecting the libations that fueled civilization

Ancient cultures used an array of ingredients to make their alcoholic beverages, including emmer wheat, wild yeast, chamomile, thyme and oregano. (Landon Nordeman)... Patrick McGovern, a 66-year-old archaeologist, wanders into the little pub, an oddity among the hip young brewers in their sweat shirts and flannel. Proper to the point of primness, the University of Pennsylvania adjunct professor sports a crisp polo shirt, pressed khakis and well-tended loafers; his wire spectacles peek out from a blizzard of white hair and beard. But Calagione, grinning broadly, greets the dignified visitor like a treasured drinking buddy. Which, in a sense, he is. ... “Dr. Pat,” as he’s known at Dogfish Head, is the world’s foremost expert on ancient fermented beverages, and he cracks long-forgotten recipes with chemistry, scouring ancient kegs and bottles for residue samples to scrutinize in the lab. He has identified the world’s oldest known barley beer (from Iran’s Zagros Mountains, dating to 3400 B.C.), the oldest grape wine (also from the Zagros, circa 5400 B.C.) and the earliest known booze of any kind, a Neolithic grog from China’s Yellow River Valley brewed some 9,000 years ago.

Widely published in academic journals and books, McGovern’s research has shed light on agriculture, medicine and trade routes during the pre-biblical era. But—and here’s where Calagione’s grin comes in—it’s also inspired a couple of Dogfish Head’s offerings, including Midas Touch, a beer based on decrepit refreshments recovered from King Midas’ 700 B.C. tomb, which has received more medals than any other Dogfish creation.

“It’s called experimental archaeology,” McGovern explains.

To devise this latest Egyptian drink, the archaeologist and the brewer toured acres of spice stalls at the Khan el-Khalili, Cairo’s oldest and largest market, handpicking ingredients amid the squawks of soon-to-be decapitated chickens and under the surveillance of cameras for “Brew Masters,” a Discovery Channel reality show about Calagione’s business.

The ancients were liable to spike their drinks with all sorts of unpredictable stuff—olive oil, bog myrtle, cheese, meadowsweet, mugwort, carrot, not to mention hallucinogens like hemp and poppy. But Calagione and McGovern based their Egyptian selections on the archaeologist’s work with the tomb of the Pharaoh Scorpion I, where a curious combination of savory, thyme and coriander showed up in the residues of libations interred with the monarch in 3150 B.C. (They decided the za’atar spice medley, which frequently includes all those herbs, plus oregano and several others, was a current-day substitute.) Other guidelines came from the even more ancient Wadi Kubbaniya, an 18,000-year-old site in Upper Egypt where starch-dusted stones, probably used for grinding sorghum or bulrush, were found with the remains of doum-palm fruit and chamomile. It’s difficult to confirm, but “it’s very likely they were making beer there,” McGovern says (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist).

Whether the hermetically sealed royal tomb discovered in 1957 in Turkey, dubbed “the Midas tumulus” and dated to 750-700 BC, actually belonged to the real-life King Midas, or his father, or his grandfather, one fact is certain: It contained more Iron-Age drinking vessels than any other site ever found. The room was filled with 157 bronze containers, many full of a bright yellow residue, which McGovern was keen to analyze.

This was the first ancient beverage McGovern and his team identified, and they were surprised at the results. “Phrygian grog,” McGovern dubbed it. The results proved this noble king was sent to the afterlife with many liters of a mixture of barley beer, grape wine, and honey mead—a blend that seemed undrinkable to the modern palate, accustomed to keeping beer and wine in their separate worlds. (“Never mix the barley and the grape,” my late grandmother admonished.) But later discoveries, such as the Jiahu site mentioned above, proved earlier civilizations had been crafting similar mixtures for many thousands of years. “If you’ve got it, ferment it,” seemed to be the spirit of the times, and discoveries in cultures to come would prove the ingenuity of using locally grown fruits, grains and other sugar sources to create alcoholic beverages (http://palatepress.com/2011/07/wine/fermentation-civilization-how-history-and-human-thirst-go-hand-in-hand/).

The smallish but mighty cacao tree, Theobroma cacao, is native to the tropics of Central and South America, and the Amazon. Its flowers are pollinated by midges, small flying insects whose work allows these flowers to grow into pods the size of an American football, containing a sweet, juicy pulp that—naturally—begins to ferment if a pod should happen to hit the ground and crack. Clay jars found in Puerto Escondido, Honduras, dating back to 1400 BC and analyzed in the lab by McGovern, held theobromine residues, proving that these people, like others proven throughout time to utilize native fruits for their fermented pleasures, made and drank a “chocolate wine.”

Just as the other beverages discovered and described above were a key component of cultural and spiritual activities, historical art and writings demonstrate that the cacao-based brew of South America—which was flavored with everything from honey, to flowers, to vanilla—also served as a form of liquid courage, celebration, and cultural touchstone. As South American culture evolved, the Mayan creation myth established humankind as originating from maize, sweet fruits and cacao. Later, Aztecs not only used cacao beans as currency, but also gave the cacao tree a central place in mythology, representing the ancestors and blood itself (http://palatepress.com/2011/07/

wine/fermentation-civilization-how-history-and-human-thirst-go-hand-in-hand/).

McGovern’s curiosity about ancient brews does not end with sheer academic analysis. Over the years, he has worked with Dogfish Head Craft Brewery in Milton, DE to actually re-create versions of the three ancient beverages mentioned in this story, based on the ingredients identified by decidedly 21st-century tactics.... Dogfish Head (motto: “Off-Centered Ales for Off-Centered People”) had a history of its own that dovetailed perfectly with McGovern’s quest. Founded as a small brewpub in 1995 by Sam Calagione, the company quickly began to invent, create and offer a head-spinning myriad of exotic brewed beverages. Brown ale made with beet sugar and raisins? It is a best-seller. A beer that includes a component from every continent—Australian ginger and South American quinoa among them? Why not?

“We’ve explored recipes and ingredients that encompass the whole culinary world,” Calagione said. “Working with the physical evidence of these ancient beverages was inspiring and exciting, to know factually what they really were, and extrapolate to come up with modern recipes.”

Those recipes include what Calagione calls “the biggest liberty we take” in his company’s commitment to maintain authenticity while recreating brews from thousands of years ago—the controlled, hygienic brewing environment. “We know what yeast we’re adding; we can control the process, which are things our ancient-brewing brethren were not able to do,” he said. “All ancient beverages probably were spoiled, in the context of today’s palate.” (http://palatepress.com/2011/07/

wine/fermentation-civilization-how-history-and-human-thirst-go-hand-in-hand/).

McGovern advises the brewers to use less za’atar; they comply. The spices are dumped into a stainless steel kettle to stew with barley sugars and hops. McGovern acknowledges that the heat source should technically be wood or dried dung, not gas, but he notes approvingly that the kettle’s base is insulated with bricks, a suitably ancient technique.

As the beer boils during lunch break, McGovern sidles up to the brewery’s well-appointed bar and pours a tall, frosty Midas Touch for himself, spurning the Cokes nursed by the other brewers. He’s fond of citing the role of beer in ancient workplaces. “For the pyramids, each worker got a daily ration of four to five liters,” he says loudly, perhaps for Calagione’s benefit. “It was a source of nutrition, refreshment and reward for all the hard work. It was beer for pay. You would have had a rebellion on your hands if they’d run out. The pyramids might not have been built if there hadn’t been enough beer.” (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=2)

Dating back at least 9,000 years, brewing beer represents our earliest attempt to harness the power of other living organisms. To be clear, I mean humankind’s first attempt at booze… at least two tree shrews, several rodents, and a small primate have been known to drink fermented palm nectar (and there’s also anecdotal evidence of drunk elephants, though scientists are dubious) (https://fangea.wordpress.com/2013/09/29/beer-our-first-biotechnology/).

“I don’t know if fermented beverages explain everything, but they help explain a lot about how cultures have developed,” he says. “You could say that kind of single-mindedness can lead you to over-interpret, but it also helps you make sense of a universal phenomenon.”

McGovern, in fact, believes that booze helped make us human. Yes, plenty of other creatures get drunk. Bingeing on fermented fruits, inebriated elephants go on trampling sprees and wasted birds plummet from their perches. Unlike distillation, which human beings actually invented (in China, around the first century A.D., McGovern suspects), fermentation is a natural process that occurs serendipitously: yeast cells consume sugar and create alcohol. Ripe figs laced with yeast drop from trees and ferment; honey sitting in a tree hollow packs quite a punch if mixed with the right proportion of rainwater and yeast and allowed to stand. Almost certainly, humanity’s first nip was a stumbled-upon, short-lived elixir of this sort, which McGovern likes to call a “Stone Age Beaujolais nouveau.” (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=5).

Thousands of years before Germany laid down its beer law, humans in every great civilization were experimenting with booze and letting their inebriated imaginations soar. These long-forgotten brewmasters were the original artisanal microbrewers, combining whatever ingredients they found around them into concoctions that don’t easily fit into today’s classifications for potent potables.

“There wasn’t beer, there wasn’t wine, there wasn’t mead. Every beverage was a hybrid,” says Sam Calagione, founder of the Dogfish Head Brewery in Delaware.

For the last dozen-plus years, Calagione and biomolecular archaeologist Patrick McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania Museum have been using chemical and plant residues found in ancient archaeological sites to rediscover the recipes of ancient booze. Some of those recipes have become special-edition beers by Dogfish Head (https://templeofmut.wordpress.com/2013/06/10/canto-talk-beer-history-and-the-manzanita-brewing-company/).

Uncorking the Past

The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages

Patrick E. McGovern (Author)

In a lively tour around the world and through the millennia, Uncorking the Past tells the compelling story of humanity's ingenious, intoxicating quest for the perfect drink. Following a tantalizing trail of archaeological, chemical, artistic, and textual clues, Patrick E. McGovern, the leading authority on ancient alcoholic beverages, brings us up to date on what we now know about how humans created and enjoyed fermented beverages across cultures. Along the way, he explores a provocative hypothesis about the integral role such libations have played in human evolution. We discover, for example, that the cereal staples of the modern world were probably domesticated for their potential in making quantities of alcoholic beverages. These include the delectable rice wines of China and Japan, the corn beers of the Americas, and the millet and sorghum drinks of Africa. Humans also learned how to make mead from honey and wine from exotic fruits of all kinds-even from the sweet pulp of the cacao (chocolate) fruit in the New World. The perfect drink, it turns out-whether it be mind-altering, medicinal, a religious symbol, a social lubricant, or artistic inspiration-has not only been a profound force in history, but may be fundamental to the human condition itself (www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520267985). Zie hier nog een filmpje erover en hier een youtube-versie.

McGovern said that wine and alcoholic beverages were an essential part of cultures in Africa, the "homeland of humanity," and around the globe as far back in time as we can go. Not only did they serve important roles as social lubricants that opened people up to one another, but they had medicinal benefits, thanks to the herbs that were dissolved easily into the alcohol. And the seemingly miraculous fermentation process and resulting mind-altering effects led to wine's central role in many religious practices, which can still be seen in our Western religions today.

Fermented beverages might have even contributed to human evolution, McGovern said. Since alcoholic beverages had fewer harmful microorganisms than water, those who drank them probably lived longer and reproduced more.

Other fun facts that McGovern offered: the ancients drank beer through straws; one species of grape (Vitis vinifera) is responsible for 99.9 percent of all wines in the world; and the modern cultivated European grapes have absolutely no genetic relation to wild European grapes, suggesting that they ultimately originated from the mountainous Near East.

McGovern noted that he has traveled the world in search of archaeological and chemical evidence for fermented beverages of all kinds and taken part in "experimental archaeology," in which he uses such evidence to re-create ancient beverages.

One of the beverages he resurrected from the Iron Age was made into a highly successful commercial product. "Midas Touch," produced by Dogfish Head Craft Brewery in Delaware, was based on a recipe McGovern extracted from residue found in vessels buried in a Turkish tomb dating to the time of King Midas, around 700 B.C. The mix of muscat grapes, barley malt, honey and saffron has won numerous medals.

"In order to understand ancient beverages, you also have to test some modern ones," McGovern added (http://ezramagazine.cornell.edu/Update/May12/EU.McGovern.uncorks.html).

Gezien zijn publicaties (met name zijn boeken) doet hij mij denken aan 'the beerhunter' Michael Jackson. Zoals hij uitzoekt waar bier (en andere alcoholische dranken; zoals Tequila) vandaan komt.

In 2000, at a Penn Museum dinner hosted by a British beer and whiskey guidebook writer, Michael Jackson, McGovern announced his intention to recreate King Midas’ last libations from the excavated residue that had moldered in museum storage for 40 years. All interested brewers should meet in his lab at 9 the next morning, he said. Even after the night’s revelry, several dozen showed up. Calagione wooed McGovern with a plum-laced medieval braggot (a type of malt and honey mead) that he had been toying with; McGovern, already a fan of the brewery’s Shelter Pale Ale, soon paid a visit to the Delaware facility.

When he first met Dr. Pat, Calagione tells the audience, “the first thing I was struck by was, ‘Oh my God, this guy looks nothing like a professor.’” The crowd roars with laughter. McGovern, buttoned into a cardigan sweater, is practically the hieroglyphic for professor. But he won over the brewer when, a few minutes into that first morning meeting, he filled his coffee mug with Chicory Stout. “He’s one of us,” Calagione says. “He’s a beer guy.” (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=6)

“Dr. Pat,” as he’s known at Dogfish Head, is the world’s foremost expert on ancient fermented beverages, and he cracks long-forgotten recipes with chemistry, scouring ancient kegs and bottles for residue samples to scrutinize in the lab. He has identified the world’s oldest known barley beer (from Iran’s Zagros Mountains, dating to 3400 B.C.), the oldest grape wine (also from the Zagros, circa 5400 B.C.) and the earliest known booze of any kind, a Neolithic grog from China’s Yellow River Valley brewed some 9,000 years ago (www.inebriatedwisdom.com/beer-trivia-of-the-day-1-6-16-earliest-beer/).

This particular brew is by Dogfish Head Brewery-- it's a part of their Ancient Ales series that aims to recreate beverages based on ancient recipes.

Ancient beverage expert Patrick McGovern refers to it as a "grog." It's technically a mixed beverage made with rice, fruit (hawthorne and grapes), and honey, which by todays standards would be a sake-wine-mead type of brew. Nowadays, we drink mostly specialized single-base beverages which makes mixed-base fermented drinks seem culturally odd (and commercially illegal in many countries), but thousands of years ago these types of drinks were the norm.

Allow me to present ancient beverages in broad strokes: our ancestors didn't have our fancy modern fermentation techniques and in-depth understanding of yeasts and fermentation that give modern day winemakers (or sake makers, or beer brewers) tight control over the final product. When the grapes weren't ripe enough our ancient ancestors may have added honey (yeasts present in the honey would have bolstered and fed the fermentation while helping to sweeten the final product). When they came to understand that grain wouldn't ferment on its own they may have malted or chewed grain to activate enzymes before mixing it with fruit and honey (the fruit and honey would have natural yeasts present to jumpstart fermentation). The choice to mix bases was partly prescribed by cultural & geographic norms (these grogs were local recipes based on available fruits and grains), and and partly due to need because the mixing helped achieve a better fermentation (which probably informed the recipes).

The modern chapter of ancient Chinese grog is twofold. On one branch, we have American interest spurred by archeologist Anne Underhill (Field Museum in Chicago). In the 1990s she initiated some of the first American-run archeological expeditions in China and felt that we would soon discover that "fermented beverages were an integral part of the earliest Chinese cultures" (McGovern 2009:28). In 1995 she enlisted the help of Patrick McGovern and his laboratory in the excavation of Liangchengzhen (a Neolithic site in Shandong Province). With his interest in Chinese Neolithic beverages piqued, McGovern went to the Yellow River basin (the birthplace of Chinese culture) with Changsui Wang (professor at University of Science & Technology in China). On one of their trips along the river they stopped at Zhengzhou and met Juzhong Zhang (of the Institute of Archeology which houses many Chinese artifacts) (www.thinking-drinking.com/blog/chinese-brew-9000-years-ago-reincarnated-as-chateau-jiahu).

Patrick McGovern '66, scientific director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, examines a sample of the ÒKing MidasÓ beverage residue under a microscope. The sample was recovered from a drinking vessel found in the Midas Tumulus at the site of Gordion in Turkey, dated ca. 740-700 B.C. Re-created ancient beverages -- Midas Touch and Chateau Jiahu -- are seen to his right and left. Photo provided by the University of Pennsylvania Museum (http://ezramagazine.cornell.edu/Update/May12/

EU.McGovern.uncorks.html).

Dogfish Head founder Sam Calagione and biomolecular archaeologist Patrick McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania Museum.... Reinheitsgebot, the German beer purity law of 1516, restricted allowable ingredients in beer to water, barley, and hops. Thousands of years before Germany laid down its beer law, humans in every great civilization were experimenting with booze, Popular Mechanics explains. The original artisanal microbrewers combined whatever ingredients they found around them into concoctions that don’t fit easily into today’s classifications. “There wasn’t beer, there wasn’t wine, there wasn’t mead,” Calagione says. “Every beverage was a hybrid.”

He and McGovern (also known as the “Indiana Jones of ancient ales, wines, and extreme beverages”) have worked together over the past dozen or so years, recreating ancient beer recipes from plant and other organic residues found in archaeological sites. (Some of these have become part of Dogfish Head’s Ancient Ales series.)

McGovern uses techniques like mass spectrometry and chromatography to parse where the remains come from. If he see traces of beeswax, for example, that’s a clue that ancient brewers used honey in their beer. Sometimes he’ll see calcium oxalate — commonly found in something known as “beerstone,” a sort of scum that forms after the brewing process — and know that people once made beer there.

The first stop on our liquid time machine was Midas Touch (750 BC), made with ingredients found in 2,700-year-old drinking vessels from the tomb of King Midas, whose funeral feast included barbequed lamb or goat and lentil stew. Somewhere between wine and mead, it’s a sweet yet dry beer made with honey, white muscat grapes, and saffron. That last ingredient is a calculated guess, based on the fact that hops didn’t become the go-to beer bittering agent until about 800 A.D., and that saffron is available in Turkey.

Next, we tasted the chronologically oldest beer of the evening, Chateau Jiahu (7000 BC), based on the oldest known fermented beverage. “The only way you could get this recipe is by chemical and botanical analysis,” McGovern says. Its ingredient list was unearthed from a 9,000-year-old tomb in China: hawthorn fruit, sake rice, barley, and honey. Beer is older than wine, did you know? The earliest date for wine is 5400 BC. (https://fangea.wordpress.com/2013/09/29/beer-our-first-biotechnology/)

the earliest chemically attested fermented beverage at Jiahu in China, c. 7000 B.C., was not a “wine” per se but a mixed or hybrid beverage made from fruits, cereal, and honey (12). It was thus a combination, wine-beer-mead. Its rice was not broken down by a specialized fungal preparation, which the Chinese uniquely developed for brewing thousands of years later, but most likely by masticating and/or sprouting the grain to make a malt. Fermented beverages, preserved as liquids, date no earlier than c. 1600–1046 B.C. in China; bronze vessels of the Shang Dynasty provide the earliest evidence. No pottery vessels were chemically confirmed to contain barley beer at Hajji Firuz Tepe in Iran (14); they were recovered from Godin Tepe, dating some 2,000 years later (www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/PhilipsreviewMIT.pdf).

Dr. Patrick E. McGovern is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. He is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology. His academic background combined the physical sciences, archaeology, and history–an A.B. in Chemistry from Cornell University, graduate work in neurochemistry at the University of Rochester, and a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Archaeology and Literature from the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department of the University of Pennsylvania.

Over the past two decades, he has pioneered the emerging field of Molecular Archaeology. In addition to being engaged in a wide range of other archaeological chemical studies, including radiocarbon dating, cesium magnetometer surveying, colorant analysis of ancient glasses and pottery technology, his endeavors of late have focused on the organic analysis of vessel contents and dyes, particularly Royal Purple, wine, and beer. The chemical confirmation of the earliest instances of these organics–Royal Purple dating to ca. 1300-1200 B.C. and wine and beer dating to ca. 3500-3100B.C.–received wide media coverage. A 1996 article published in Nature, the international scientific journal, pushed the earliest date for wine back another 2000 years–to the Neolithic period (ca. 5400-5000B.C.).

His research–showing what Molecular Archaeology is capable of achieving—has involved reconstructing the “King Midas funerary feast” (Nature 402, Dec. 23, 1999: 863-64) and chemically confirming the earliest fermented beverage from anywhere in the world—Neolithic China, some 9000 years ago, where pottery jars were shown to contain a mixed drink of rice, honey, and grape/hawthorn tree fruit (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 101.51: 17593-98). Most recently, he and colleagues identified the earliest beverage made from cacao (chocolate) from a site in Honduras, dated to ca. 1150 B.C., and an herbal wine from Dynasty 0 in Egypt. (https://www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology/?page_id=10)

The shelves of McGovern’s office in the University of Pennsylvania Museum are packed with sober-sounding volumes—Structural Inorganic Chemistry, Cattle-Keepers of the Eastern Sahara—along with bits of bacchanalia. There are replicas of ancient bronze drinking vessels, stoppered flasks of Chinese rice wine and an old empty Midas Touch bottle with a bit of amber goo in the bottom that might intrigue archaeologists thousands of years hence. There’s also a wreath that his wife, Doris, a retired university administrator, wove from wild Pennsylvania grape vines and the corks of favorite bottles. But while McGovern will occasionally toast a promising excavation with a splash of white wine sipped from a lab beaker, the only suggestion of personal vice is a stack of chocolate Jell-O pudding cups.

The scientific director of the university’s Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health, McGovern had had an eventful fall. Along with touring Egypt with Calagione, he traveled to Austria for a conference on Iranian wine and also to France, where he attended a wine conference in Burgundy, toured a trio of Champagne houses, drank Chablis in Chablis and stopped by a critical excavation near the southern coast.

Yet even strolling the halls with McGovern can be an education. Another professor stops him to discuss, at length, the folly of extracting woolly mammoth fats from permafrost. Then we run into Alexei Vranich, an expert on pre-Columbian Peru, who complains that the last time he drank chicha (a traditional Peruvian beer made with corn that has been chewed and spit out), the accompanying meal of roast guinea pigs was egregiously undercooked. “You want guinea pigs crunchy, like bacon,” Vranich says. He and McGovern talk chicha for a while. “Thank you so much for your research,” Vranich says as he departs. “I keep telling people that beer is more important than armies when it comes to understanding people.” (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=2) (www.heritagedaily.com/2013/06/new-biomolecular-archaeological-evidence-points-to-the-beginnings-of-viniculture-in-france/90672)

In spite of The Comic Book Story of Beer‘s contention that the no brewing was ever carried out in the entire ancient history of Italy, as it turns out the pre-Roman Etruscan civilization had a taste for ales, and in fact brewed them. Supporting evidence for this Etruscan zythophilia has been found in drinking vessels found in 2,800 year-old burial vaults.

So let’s toast intellectual honesty! We are happy, in the name of academic best practices, to admit this one slipped through our fingers, and we are grateful to be able to share the correction with you (www.thecomicbookstoryofbeer.com/with-dr-patrick-e-mcgovern/).

So, which came first you think: beer… or bread? More specifically, is the first cultivation of grain — and ultimately, our settling down from a nomadic life — about making bread or is it about making beer? (https://fangea.wordpress.com/2013/09/29/beer-our-first-biotechnology/)

As a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Patrick McGovern, 71, is a modern brewmaster of the ancient empires. By extracting organic material left at archaeological sites, he and Dogfish Head Brewery re-create humankind’s first alcoholic beverages. So far, these include a beer likely served at King Midas’s funerary feast, and a 9,000-year-old fermented rice and honey drink from Neolithic China—which, McGovern says, still “goes very well with Chinese food.” We asked the “Indiana Jones of alcohol” to dig into mankind’s relationship with libations (www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/3-questions-patrick-mcgovern/).

Why did humans start drinking?

We were born to drink—first milk, then fermented beverages. Our sensory organs attract us to them. As humans came out of Africa, they developed these from what they grew. In the Middle East, it was barley and wheat. In China, rice and sorghum. Alcohol is central to human culture and biology because we were probably drinking fermented beverages from the beginning. We’re set up to drink them (www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/3-questions-patrick-mcgovern/).

How did alcohol shape civilization?

Anthropologists debate which came first, bread or beer. I think it was beer: It’s easier to make, more nutritious, and has a mind-altering effect. These were incentives for hunter-gatherers to settle down and domesticate grain. In the process they set up the first permanent villages and broke down social boundaries between groups. Most of the world’s religions use alcohol, and the earliest medicines involve wine. The beginnings of civilization were spurred on by fermented beverages.

In what way?

Alcohol is very important as a social lubricant. If you were an early hunter-gatherer society it helps to have a group working together. After hunting you’d come back and a fermented beverage would bring people together. In Western culture today we tend to think of alcoholic beverages as a recreational activity, but it has probably always been partly that way because they break down boundaries between people—if you don’t drink inordinate amounts (www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/3-questions-patrick-mcgovern/).

How did alcohol affect religion?

The process of fermentation itself is very mysterious: It’s bubbling away as carbon dioxide comes off. You see this and think, There’s got to be something special at work. When you take a drink of it and get a mind-altering effect, that’s associated with an outside force communicating via this beverage. So if we look at most of the religions around the world they have a fermented beverage central to them (www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/3-questions-patrick-mcgovern/).

But is it healthy?

Alcohol is good for you. We’re biologically adapted to moderate drinking: It kills harmful bacteria. If you were in a situation two million years ago where your life expectancy may only be 20 years, you’d look for anything that may extend it or keep disease to a minimum. What choice did you have? If you just drink raw water you run a very high risk of getting disease, and people would have empirically realized that. They see that a guy drinking out of the stream died, but the guy drinking alcohol lived to be 30 (www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/3-questions-patrick-mcgovern/).

Why aren't the medicinal benefits more widely known?

The earliest medicines from the Romans and Greeks involve a lot of wine. Every kind of wine has a special medicinal effect. Up until a hundred years ago alcoholic beverages were the prime medicine. That may explain why a lot of doctors want to find out about my research—they don’t know how pervasive these beverages were and how far back they go. That’s a carryover of prohibition: Doctors stress the negative side even though they enjoy fermented beverages. For a long time the medical community just said it was detrimental. Then they found out a glass or two of wine a day is better than not having any (www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/3-questions-patrick-mcgovern/).

New biomolecular archaeological evidence backed up by increasingly sophisticated scientific testing techniques are uncovering medicinal remedies discovered, tested, and sometimes lost, throughout millennia of human history—herbs, tree resins, and other organic materials dispensed by ancient fermented beverages like wine and beer. Did those ancient “remedies” work-and if so, is there something we can learn—or re-learn—from our ancestors to help sick people today?

The answer is now a definitive yes, thanks to early positive results from laboratory testing conducted by researchers at Penn Medicine’s Abramson Cancer Center working in collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory run by archaeochemist and ancient alcohol expert Patrick E. McGovern, PhD.

Over the past two years, researchers working on a unique joint project, “Archaeological Oncology: Digging for Drug Discovery,” have been testing compounds found in ancient fermented beverages from China and Egypt for their anticancer properties. Several compounds—specifically luteolin from sage and ursolic acid from thyme and other herbs attested in ancient Egyptian wine jars, ca 3150 BCE, and artemisinin and its synthetic derivative, artesunate, and isoscopolein from wormwood species (Artemisia), which laced an ancient Chinese rice wine, ca 1050 BCE—showed promising and positive test tube activity against lung and colon cancers (www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology1/).

How can we drink like our ancestors?

When analyzing something, I work from a minuscule amount of chemical, botanical, and archaeological data. I look for principal ingredients: Does it have a grain? A fruit? An herb? Then I take bits of information from texts or frescoes and re-create the process, replicating pottery or collecting local yeast. Some methods carry on for thousands of years. In Burkina Faso they still mash carbs into sugar exactly how the ancient Egyptians did in 3500 B.C. (www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/3-questions-patrick-mcgovern/).

When did you first discover a passion for alcohol?

I traveled to Germany when I was 16 years old and had my first beer. The reason was because it cost less than the Coca-Cola. Then I discovered it also made you feel very good. As I got more involved in the research and had opportunities to do tastings I'd try to see the different nuances of flavor. You can’t understand the ancient beverages unless you taste the modern ones (www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/3-questions-patrick-mcgovern/).

One summer, during which McGovern was “partly in grad school,” he says with the vagueness frequently reserved for the ’70s, he and Doris toured the Middle East and Europe, living on a few dollars a day. En route to Jerusalem, they found themselves wandering Germany’s Mosel wine region, asking small-town mayors if local vintners needed seasonal pickers. One winemaker, whose arbors dotted the steep slate slopes above the Moselle River, took them on, letting them board in his house.

The first night there, the man of the house kept returning from his cellar with bottle after bottle, McGovern recalls, “but he wouldn’t ever show us what year it was. Of course, we didn’t know anything about vintage, because we had never really drunk that much wine, and we were from the United States. But he kept bringing up bottle after bottle without telling us, and by the end of the evening, when we were totally drunk—the worst I’ve ever been, my head going around in circles, lying on the bed feeling like I’m in a vortex—I knew that 1969 was terrible, ’67 was good, ’59 was superb.”

McGovern arose the next morning with a seething hangover and an enduring fascination with wine (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=4).

De anekdote over de Moselwijn zou rond zijn 26e zijn geweest volgens zijn presentatie uit 2012 bij Cornell University Department of Horticulture.

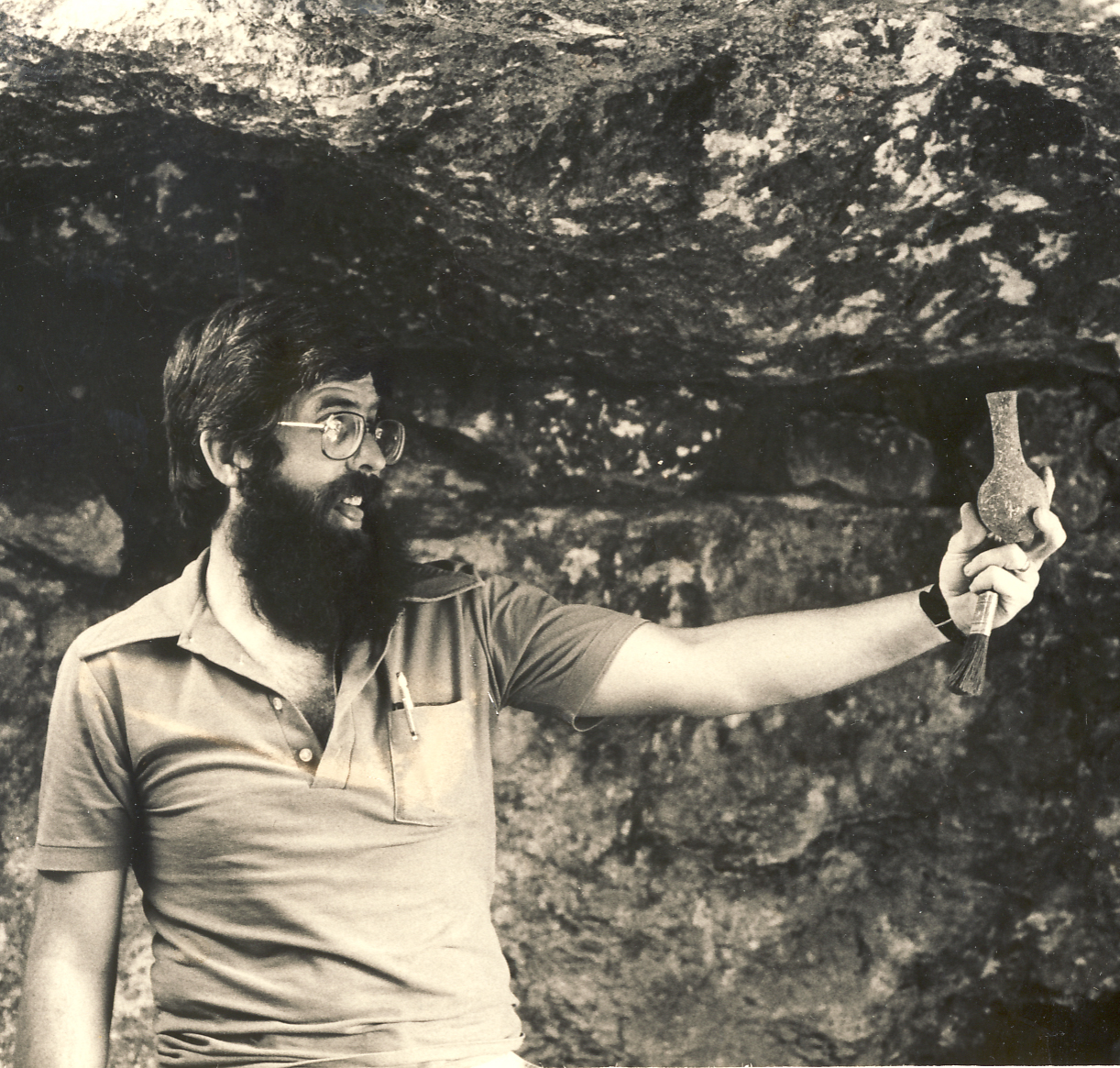

Earning his PhD in Near Eastern archaeology and history from the University of Pennsylvania, he ended up directing a dig in Jordan’s Baq’ah Valley for more than 20 years, and became an expert on Bronze and Iron Age pendants and pottery. (He admits he was once guilty of scrubbing ancient vessels clean of all their gunk.) By the 1980s, he had developed an interest in the study of organic materials—his undergraduate degree was in chemistry—including jars containing royal purple, a once-priceless ancient dye the Phoenicians extracted from sea snail glands. The tools of molecular archaeology were swiftly developing, and a smidgen of sample could yield surprising insights about foods, medicines and even perfumes. Perhaps ancient containers were less important than the residues inside them, McGovern and other scholars began to think.

A chemical study in the late 1970s revealed that a 100 B.C. Roman ship wrecked at sea had likely carried wine, but that was about the extent of ancient beverage science until 1988, when a colleague of McGovern’s who’d been studying Iran’s Godin Tepe site showed him a narrow-necked pottery jar from 3100 B.C. with red stains.

“She thought maybe they were a wine deposit,” McGovern remembers. “We were kind of skeptical about that.” He was even more dubious “that we’d be able to pick up fingerprint compounds that were preserved enough from 5,000 years ago.”

But he figured they should try. He decided tartaric acid was the right marker to look for, “and we started figuring out different tests we could do. Infrared spectrometry. Liquid chromatography. The Feigl spot test....They all showed us that tartaric acid was present,” McGovern says.

He published quietly, in an in-house volume, hardly suspecting that he had discovered a new angle on the ancient world. But the 1990 article came to the attention of Robert Mondavi, the California wine tycoon who had stirred some controversy by promoting wine as part of a healthy lifestyle, calling it “the temperate, civilized, sacred, romantic mealtime beverage recommended in the Bible.” With McGovern’s help, Mondavi organized a lavishly catered academic conference the next year in Napa Valley. Historians, geneticists, linguists, oenologists, archaeologists and viticulture experts from several countries conferred over elaborate dinners, the conversations buoyed by copious drafts of wine. “We were interested in winemaking from all different perspectives,” McGovern says. “We wanted to understand the whole process—to figure out how they domesticated the grape, and where did that happen, how do you tend grapes and the horticulture that goes into it.” A new discipline was born, which scholars jokingly refer to as drinkology, or dipsology, the study of thirst.

Back at Penn, McGovern soon began rifling through the museum’s storage-room catacombs for promising bits of pottery. Forgotten kitchen jars from a Neolithic Iranian village called Hajji Firuz revealed strange yellow stains. McGovern subjected them to his tartaric acid tests; they were positive. He’d happened upon the world’s oldest-known grape wine (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=4).

Tartaric acid. C15H31COOC30H61, otherwise known as beeswax. Phytosterols indicating a temperate-climate grain such as rice. These sterile-sounding compounds were all that remained in ancient jars, buried with the dead in Jiahu to ensure a well-sated afterlife. What the jars ensured, as well, was that many thousands of years later, we would gain keen insight into the way past cultures interacted with both their deceased and their fermented beverages.

The buried beverage, analyzed via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS); carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis; and infrared spectrometry, was determined to contain a mixture of native-grape and hawthorn-fruit wine (the tartaric-acid component), honey mead (the beeswax component), and rice beer (the grain component). This finding marked the earliest use of grape as an ingredient in a fermented beverage anywhere in the world. After he examined the carved-bone flutes found in the grave, and studied writings reflecting the time, McGovern ascertained that the beverages were merely one part of an intricate religious funeral ceremony involving music, food, dance and divination, with consumption of the local mixed-fermented beverage a crucial aspect of connecting the mortal and the spirit worlds (http://palatepress.com/2011/07/wine/fermentation-civilization-how-history-and-human-thirst-go-hand-in-hand/).

“There is an alcoholic haze at the center of our galaxy.”

No, that sentence isn’t an example of fuzzy-headed navel-gazing after a night of over-imbibing. It is an excerpt from Dr. Patrick E. McGovern’s 2009 book “Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages,” and it refers to the huge clouds of methanol, ethanol and vinyl ethanol that exist in space—one of which stretches near the center of the Milky Way. It is hypothesized that this vinyl ethanol, contained in dust particles and frozen into comets, may have introduced the first building blocks of life on Earth. If that is the case, is it any wonder human civilization developed from the start with a drive to create—and consume—fermented beverages?

McGovern (prepare yourself for the best job title ever) is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. He began his archaeological career as a student of pottery. Later, fascinated by the idea that new technology could potentially identify beverage residues often found inside excavated vessels, he became a pioneer in the field of analyzing these chemical fingerprints, which led to the discovery of the earliest-known fermented beverages from a variety of cultures. McGovern recently presented a lecture at the Getty Villa in Malibu, CA, where he illuminated his findings in a combination of archaeological discovery; scientific investigation; and the study of ancient texts and art, demonstrating the historical importance of alcohol in human culture, society and religion.

“Life is based on fermentation,” McGovern said. While the statement can be interpreted literally (it is believed that glycolysis—sugar fermentation—was the first form of energy production for life on Earth), it also speaks to the broader fact that nearly every single creature on the planet—from fig wasps, to elephants, to modern-day humans clinking crystal goblets—is attracted to the alcohol that results from the natural fermentation of yeast and sugar. The oldest discovered alcoholic beverage residue, from 9,000-year-old vessels unearthed at a gravesite in Jiahu, China, proves our forebears were both innovative and reverent in their creation and use of local “grog.” (http://palatepress.com/2011/07/wine/fermentation-civilization-how-history-and-human-thirst-go-hand-in-hand/)

Residues extracted from the drinking set of King Midas—who ruled over Phrygia, an ancient district of Turkey—had languished in storage for 40 years before McGovern found them and went to work. The artifacts contained more than four pounds of organic materials, a treasure—to a biomolecular archaeologist—far more precious than the king’s fabled gold. But he’s also adamant about travel and has done research on every continent except Australia (though he has lately been intrigued by Aborigine concoctions) and Antarctica (where there are no sources of fermentable sugar, anyway). McGovern is intrigued by traditional African honey beverages in Ethiopia and Uganda, which might illuminate humanity’s first efforts to imbibe, and Peruvian spirits brewed from such diverse sources as quinoa, peanuts and pepper-tree berries. He has downed drinks of all descriptions, including Chinese baijiu, a distilled alcohol that tastes like bananas (but contains no banana) and is approximately 120 proof, and the freshly masticated Peruvian chicha, which he is too polite to admit he despises. (“It’s better when they flavor it with wild strawberries,” he says firmly.)

Partaking is important, he says, because drinking in modern societies offers insight into dead ones (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=5).

The debate over the pros and cons of alcohol shows little sign of abating. I would add another confounding ingredient to the mix: it is quite possible that much of what we consider uniquely human—music, dance, theater, religious storytelling and worship, language, and a thought process that would eventually become science—were stimulated by the creation and consumption of alcoholic beverages during the Paleolithic period, which encompasses some 95 percent of our largely unknown hominin history. Our ancestors must have been astounded by the process of fermentation itself, as the liquid mysteriously churned and was transformed into another substance with psychoactive properties. And much more surely remains to be discovered (www.scientificamerican.com/article/alcohol-an-astonishing-molecule/).

... how can he [Rod Phillips] conclude that we have entered a “post-alcohol era,” especially when the worlds of craft beer, cocktail innovation, mead making, etc. are enjoying revivals around the world? (www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/PhilipsreviewMIT.pdf)

Brewing Relics: Archaeologist Patrick McGovern uncovers the secrets of ancient ales and wines

April 30, 2018 by Jessica Searles

The mouth of a perfectly contented man is filled with beer.” While this sounds like an adage uttered by an 18th century figure like Ben Franklin, it is in fact an inscription found in Dendera, Egypt, dating back to 2200 B.C.

Egyptians drank beer on a daily basis. ... And beer was often used throughout Egypt as compensation for labor ... “Fermented beverages clearly eased the difficulties of everyday life” and “lubricated the social fabric by bringing human groups together,” explains Dr. Patrick McGovern, who is a pioneering figure in the field of molecular archaeology.

Often called the “Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages,” uncovering the history of fermented drink is a normal day on the job for Dr. McGovern, whose official titles include Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project and Adjunct Professor of Anthropology at the Penn Museum.

...

Dr. McGovern first encountered the complexities of fermented beverages through his experiences of wine when he toured Europe and the Middle East during grad school. While passing through Germany, he acquired a seasonal job as a grape picker near the Moselle River. On his first night there, the owner would not stop bringing up bottles of wine from the cellar. Dr. McGovern awoke the next morning with two very strong, but very different impressions: the weight of a massive hangover and a fascination for fermented beverages.

By 1980, he had earned his Ph.D.—and nearly a decade of experience with excavations—when he was approached by a colleague who was studying Iran’s Godin Tepe site. She showed Dr. McGovern a vessel from the site dating to around 3100 B.C., which had staining she thought could be wine. As a fairly new science, chemical tests were available to determine if tartaric acid, a compound found in grapes, was present in the leftover residue. They were both skeptical that they would find evidence of wine, but gave it a go anyway and, much to their surprise, indeed found tartaric acid in the vessel. Dr. McGovern published on the discovery, and the rest is history—ancient history to be more precise.

In the late 1990s, Dr. McGovern was asked to test a feasting set discovered within the tomb of King Midas in central Turkey, and which had been sitting in the Penn Museum since 1957. His analysis revealed that the king was drinking what seemed to be a mixture of wine, beer, and mead (Now that’s some gold!).... In March of 2000, ... challenging a room full of brewers to replicate the drink shared at the funerary feast of King Midas circa 700 B.C. Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head answered the call and teamed up with Dr. McGovern to brew the appropriately named Midas Touch, which has gone on to earn multiple medals from Great American Beer Festival, World Beer Cup, and other beer competitions.

With Midas Touch gleaming with success, Dr. McGovern continued to collaborate with Dogfish Head on its Ancient Ales series. He traveled to Jiahu, China, and came back with another ancient beverage for the brewery to replicate. The drink, which McGovern identified as being made of rice, honey, hawthorn, and grape, is—thus far—the oldest chemically confirmed alcoholic beverage in the world at a healthy 9,000 years old. Dogfish Head and Dr. McGovern translated it into Chateau Jiahu, a favorite of the archaeologist, who swears it is “an ideal complement to Asian foods.” Dr. McGovern’s work with the Ancient Ales series has yielded other beers, such as Ta Henket, an ale made from ingredients and traditions plucked from Egyptian hieroglyphics; Birra Etrusca Bronze, inspired by drinking vessels found in 2,800-year-old Etruscan tombs; and Theobroma, the earliest known alcoholic cocoa-based drink that dates back to 1200 B.C. in Honduras. (https://growlermag.com/brewing-relics-archaeologist-patrick-mcgovern-uncovers-the-secrets-of-ancient-ales-and-wines/)

Over the past two decades, he has pioneered the emerging field of Molecular Archaeology. In addition to being engaged in a wide range of other archaeological chemical studies, including radiocarbon dating, cesium magnetometer surveying, colorant analysis of ancient glasses and pottery technology, his endeavors of late have focused on the organic analysis of vessel contents and dyes, particularly Royal Purple, wine, and beer. The chemical confirmation of the earliest instances of these organics–Royal Purple dating to ca. 1300-1200 B.C. and wine and beer dating to ca. 3500-3100B.C.–received wide media coverage. A 1996 article published in Nature, the international scientific journal, pushed the earliest date for wine back another 2000 years–to the Neolithic period (ca. 5400-5000B.C.).

His research–showing what Molecular Archaeology is capable of achieving—has involved reconstructing the “King Midas funerary feast” (Nature 402, Dec. 23, 1999: 863-64) and chemically confirming the earliest fermented beverage from anywhere in the world—Neolithic China, some 9000 years ago, where pottery jars were shown to contain a mixed drink of rice, honey, and grape/hawthorn tree fruit (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 101.51: 17593-98). Most recently, he and colleagues identified the earliest beverage made from cacao (chocolate) from a site in Honduras, dated to ca. 1150 B.C., and an herbal wine from Dynasty 0 in Egypt.

He is the author of Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton University Press, 2003), and most recently, Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages (Berkeley: University of California, 2009). In addition to over 100 periodical articles, McGovern has also written or edited 10 books, including The Origins and Ancient History of Wine (Gordon and Breach, 1996), Organic Contents of Ancient Vessels (MASCA, 1990), Cross-Craft and Cross-Cultural Interactions in Ceramics (American Ceramic Society, 1989), and Late Bronze Palestinian Pendants: Innovation in a Cosmopolitan Age (Sheffield, 1985). In 2000, his book on the Foreign Relations of the “Hyksos,” a scientific study of Middle Bronze pottery in the Eastern Mediterranean, was published by Archaeopress.

As a Research Associate in the Near East Section of the Museum, he has also directed the Baq`ah Valley (Jordan) Project over the past 25 years (described in a University Museum monograph, The Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Central Transjordan, 1986), and been involved with many other excavations throughout the Middle East as a pottery and stratigraphic consultant. A detailed study of the New Kingdom Egyptian garrison at Beth Shan, an older Museum excavation, also appeared in 1994 in the Museum Monograph series, entitled The Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan.

As an Adjunct Professor in the Anthropology Dept. at Penn, he teaches courses on Molecular Archaeology (http://www.penn.museum/sites/biomoleculararchaeology/?page_id=10).

The earliest known chemical evidence of beer dates to circa 3500–3100 BC from the site of Godin Tepe in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran (www.inebriatedwisdom.com/beer-trivia-of-the-day-1-6-16-earliest-beer/).

McGovern can’t simply look for the presence of alcohol, which survives barely a few months, let alone millennia, before evaporating or turning to vinegar. Instead, he pursues what are known as fingerprint compounds. For instance, traces of beeswax hydrocarbons indicate honeyed drinks; calcium oxalate, a bitter, whitish byproduct of brewed barley also known as beer stone, means barley beer.

Tree resin is a strong but not surefire indicator of wine, because vintners of old often added resin as a preservative, lending the beverage a pleasing lemony flavor (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=3).

Archaeology is, at heart, a destructive science, McGovern recently told an audience at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian: “Every time you excavate, you destroy.” (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=6)

Dr. Patrick E. McGovern is Senior Research Scientist with the Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology (MASCA) and Adjunct Associate Professor with the Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Museum. He received his degrees from Cornell University (A.B. in Chemistry) and the University of Pennsylvania (Ph.D. in Near Eastern Archaeology and History). His areas of specialization include biomolecular Archaeology, the archaeology of the Near East and Egypt (particularly Bronze Age), ancient DNA, organic contents analysis, pottery provenancing, and technological innovation and cultural change. He has published ten books and over 100 articles, his most recent work is “Uncorking the Past: The Human Quest for Alcoholic Beverages” (2009, University of California) (http://aia.archaeological.org/webinfo.php?page=10224&lid=202).

Once the boiling brown pottery mixture cooks down to a powder, says Gretchen Hall, a researcher collaborating with McGovern, they’ll run the sample through an infrared spectrometer. That will produce a distinctive visual pattern based on how its multiple chemical constituents absorb and reflect light. They’ll compare the results against the profile for tartaric acid. If there’s a match or a near-match, they may do other preliminary checks, like the Feigl spot test, in which the sample is mixed with sulfuric acid and a phenol derivative: if the resulting compound glows green under ultraviolet light, it most likely contains tartaric acid. So far, the French samples look promising.

McGovern already sent some material to Armen Mirzoian, a scientist at the federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, whose primary job is verifying the contents of alcoholic beverages—that, say, the gold flakes in the Italian-made Goldschlager schnapps are really gold. (They are.) His Beltsville, Maryland, lab is crowded with oddities such as a confiscated bottle of a distilled South Asian rice drink full of preserved cobras and vodka packaged in a container that looks like a set of Russian nesting dolls. He treats McGovern’s samples with reverence, handling the dusty box like a prized Bordeaux. “It’s almost eerie,” he whispers, fingering the bagged sherds inside. “Some of these are 5,000, 6,000 years old.” (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist=&page=3).

By analyzing ancient pottery, Patrick McGovern is resurrecting the libations that fueled civilization

Ancient cultures used an array of ingredients to make their alcoholic beverages, including emmer wheat, wild yeast, chamomile, thyme and oregano. (Landon Nordeman)... Patrick McGovern, a 66-year-old archaeologist, wanders into the little pub, an oddity among the hip young brewers in their sweat shirts and flannel. Proper to the point of primness, the University of Pennsylvania adjunct professor sports a crisp polo shirt, pressed khakis and well-tended loafers; his wire spectacles peek out from a blizzard of white hair and beard. But Calagione, grinning broadly, greets the dignified visitor like a treasured drinking buddy. Which, in a sense, he is. ... “Dr. Pat,” as he’s known at Dogfish Head, is the world’s foremost expert on ancient fermented beverages, and he cracks long-forgotten recipes with chemistry, scouring ancient kegs and bottles for residue samples to scrutinize in the lab. He has identified the world’s oldest known barley beer (from Iran’s Zagros Mountains, dating to 3400 B.C.), the oldest grape wine (also from the Zagros, circa 5400 B.C.) and the earliest known booze of any kind, a Neolithic grog from China’s Yellow River Valley brewed some 9,000 years ago.

Widely published in academic journals and books, McGovern’s research has shed light on agriculture, medicine and trade routes during the pre-biblical era. But—and here’s where Calagione’s grin comes in—it’s also inspired a couple of Dogfish Head’s offerings, including Midas Touch, a beer based on decrepit refreshments recovered from King Midas’ 700 B.C. tomb, which has received more medals than any other Dogfish creation.

“It’s called experimental archaeology,” McGovern explains.

To devise this latest Egyptian drink, the archaeologist and the brewer toured acres of spice stalls at the Khan el-Khalili, Cairo’s oldest and largest market, handpicking ingredients amid the squawks of soon-to-be decapitated chickens and under the surveillance of cameras for “Brew Masters,” a Discovery Channel reality show about Calagione’s business.

The ancients were liable to spike their drinks with all sorts of unpredictable stuff—olive oil, bog myrtle, cheese, meadowsweet, mugwort, carrot, not to mention hallucinogens like hemp and poppy. But Calagione and McGovern based their Egyptian selections on the archaeologist’s work with the tomb of the Pharaoh Scorpion I, where a curious combination of savory, thyme and coriander showed up in the residues of libations interred with the monarch in 3150 B.C. (They decided the za’atar spice medley, which frequently includes all those herbs, plus oregano and several others, was a current-day substitute.) Other guidelines came from the even more ancient Wadi Kubbaniya, an 18,000-year-old site in Upper Egypt where starch-dusted stones, probably used for grinding sorghum or bulrush, were found with the remains of doum-palm fruit and chamomile. It’s difficult to confirm, but “it’s very likely they were making beer there,” McGovern says (www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-beer-archaeologist-17016372/?no-ist).

(Photo: Dr. Patrick Mcgovern on the right with Dogfish Head’s Sam Calagione)

The world’s foremost beer archaeologist, Patrick has collaborated with Dogfish Head Craft Brewery to recreate several of these ancient beverages. We’ll sample some of the best of these limited edition brews on March 2nd. ( Patrick is seen here on the right with Dogfish Head’s founder, Sam Calagione, sampling one of their concoctions .) (www.wctrust.org/?page_id=1631)

Whether the hermetically sealed royal tomb discovered in 1957 in Turkey, dubbed “the Midas tumulus” and dated to 750-700 BC, actually belonged to the real-life King Midas, or his father, or his grandfather, one fact is certain: It contained more Iron-Age drinking vessels than any other site ever found. The room was filled with 157 bronze containers, many full of a bright yellow residue, which McGovern was keen to analyze.