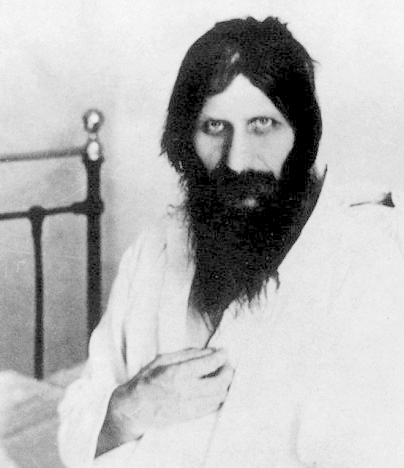

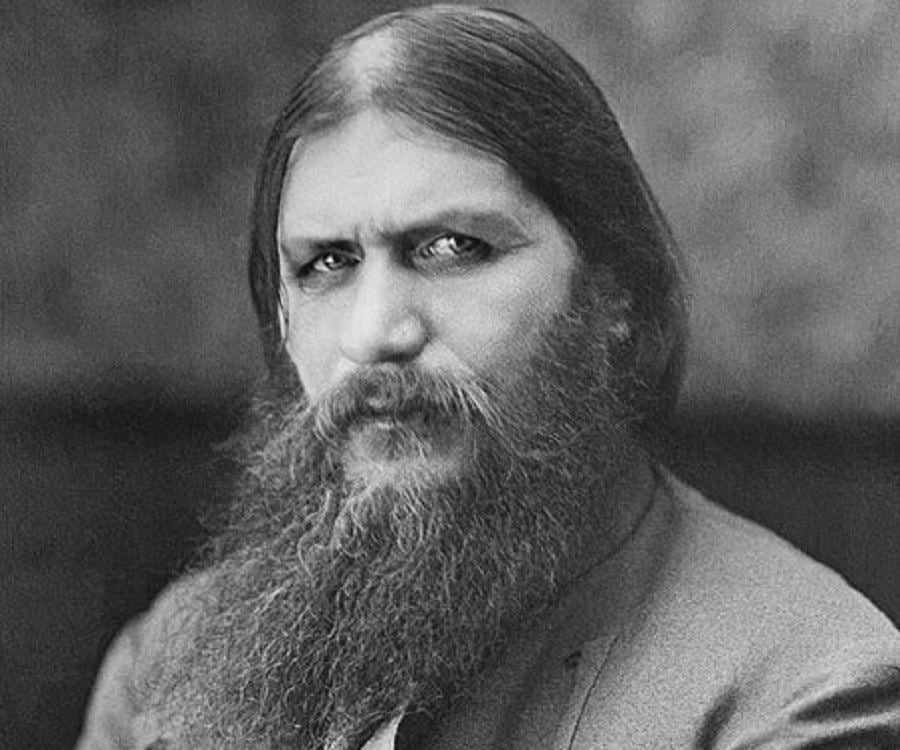

Grigori Jefimovitsj Raspoetin (Russisch: Григорий Ефимович Распутин), (Pokrovskoje, 21 januari [O.S. 9 januari] 1869 - Petrograd, 30 december [O.S. 17 december] 1916) was een Russische starets in wording. Beter is het om hem een strannik (een rondreizende pelgrim) te noemen. Hij kwam aan het hof van de tsaar Nicolaas II van Rusland als geestelijk leidsman. Twee jaar later werd hij uitgenodigd als gebedsgenezer voor zijn zoon, de tsarevitsj Aleksej Nikolajevitsj van Rusland, die aan hemofilie leed. Raspoetin boekte daarmee opvallend succes. Hij verwierf de vriendschap bij de tsarina Alexandra Fjodornova, die hem als redder van haar zoon zag. Hij begon zich in staatsaangelegenheden te mengen nadat de tsaar zich in augustus 1915 naar het front begaf als opperbevelhebber. Raspoetin werd na een jaar zowel door rechtse als linkse krachten in de politiek gezien als de oorzaak van de penibele toestand in het keizerlijke Rusland en is eind december 1916 door monarchisten, bevreesd voor zijn invloed op de tsarina, afgemaakt met pistoolschoten (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grigori_Raspoetin).

Rasputin is best known for his role as a mystical adviser in the court of Czar Nicholas II of Russia.Grigori Rasputin was born into a peasant family in Siberia, Russia, around 1869. After failing to become a monk, Rasputin became a wanderer and eventually entered the court of Czar Nicholas II because of his alleged healing abilities. Known for his prophetic powers, he became a favorite of the Nicholas's wife, Alexandra Feodorovna, but his political influence was minor. Rasputin became swept up in the events of the Russian Revolution and met a brutal death at the hands of assassins in 1916 (www.biography.com/people/rasputin-9452162).

Born in 1872 at Pokrovskoye in Siberia to a peasant family, Rasputin's limited education left him without the ability to either read or write. Even at a young age he earned himself such a reputation for devoted debauchery that his actual name of Grigory Yefimovich Novykh was replaced with the surname 'Rasputin' - Russian for 'debauched one'.

Having undergone a form of religious conversion while aged 18 Rasputin embraced the Khlysty sect. Happily for Rasputin (given his reputation) the sect preached the notion that the closest relationship to God could best be achieved while exhausted from prolonged sexual engagements.

Rasputin married at age 19, to Proskovia Fyodorovna, who bore him four children. Unsettled, Rasputin left his wife and travelled, variously to Greece and Jerusalem, where he established a reputation (self-created) as a holy man.

Winding up in St. Petersburg in 1903 Rasputin met up with the the Bishop of Saratov, Hermogen. Since the Romanov court at that time was dabbling in mysticism Rasputin was recommended in 1905 by Hermogen to the royal couple (www.firstworldwar.com/bio/rasputin.htm).

Raspoetin kwam uit een boerenfamilie uit het district Tjoemen in West-Siberië. ...Zijn broer Dimitri en een zuster Maria verdronken beiden in een rivier. Bij het redden van zijn broer uit de rivier de Tura liepen Dimitri en Grigori een pneumonie op. Dimitri overleed hieraan. Tijdens zijn ziekbed zou Grigori in een droom Maria hebben gezien. Toen er in het dorp een paardendief actief was, wees hij naar verluidt de dader aan. Hij kreeg hierdoor de reputatie over speciale gaven te beschikken.[3] Toen hij in zijn jeugd tweemaal beschuldigd werd van diefstal en hierbij hardhandig werd aangepakt, merkten dorpsbewoners op dat Grigori vreemd reageerde. In plaats van terug te vechten onderging hij zijn straf gelaten. Anderen zagen hierin het bewijs van een persoonlijkheidsverandering, waarin lijden voor hem een speciale betekenis kreeg.[2] Desondanks zou Grigori losbandig hebben geleefd in het dorp. Zo was hij regelmatig dronken en noemden dorpsgenoten hem Grisjka de dwaas.[4] Hij was gewelddadig, vocht vaak[1] en zou zich veelvuldig hebben beziggehouden met het versieren van jonge meisjes....Hij reisde maanden als religieuze pelgrim en gebedsgenezer zonder zich te wassen of zich te verkleden en hield zich in leven door giften.

In 1902 verbleef hij in de stad Kazan bij de rivier de Wolga. Daar stichtte hij met een aantal volgelingen een commune. Ondanks zijn onhygiënische levenswijze maakte hij met zijn charisma en kennis van de Bijbel een grote indruk op zijn omgeving, waar hij steeds meer werd beschouwd als een 'heilige man'. Met een aanbeveling op zak trok Raspoetin naar Sint-Petersburg. Daar ontmoette hij Johannes van Kronstadt, Theofan en Hermogen, de bisschop van Saratov....Zijn aanhang onder de aristocratie, en dan met name het vrouwelijke deel, groeide snel. Raspoetin had dan ook een grote schare bewonderaars. Verschillende vrouwen onderhielden hem zodat hij in welstand kon leven. Een van deze dames was Olga Lochtina, een aristocrate die ziek was, genezen werd en vervolgens besloot Raspoetin te dienen. Zij nodigde hem uit bij hen te wonen gedurende zijn verblijf in Sint-Petersburg.

Hij maakte pas begin in november 1905[3] contact met de tsaar en zijn vrouw tijdens een bezoek aan Militza van Montenegro. In 1907 werd Raspoetin in het paleis uitgenodigd omdat tsarevitsj Aleksei Nikolajevitsj, de zoon van de tsaar, ten gevolge van hemofilie een bloeduitstorting had. Dat de jongen aan hemofilie leed was aan niemand bekend. Raspoetin "genas" de jongen met zijn helende krachten, maar waarschijnlijker is dat hij het deed door een aantal reguliere medicijnen, zoals aspirine, desastreus voor een hemofiliepatiënt, te verbieden. Hij wist zo het vertrouwen te winnen van Aleksandra Fjodorovna, de tsarina. Over de redenen achter de effectiviteit van de 'behandelingen' wordt nog steeds druk gespeculeerd. Hoe het ook zij, iedere keer wanneer Raspoetin bij de tsarevitsj werd geroepen, voelde de jongen zich vrij snel daarna een stuk beter. Met het vertrouwen nam ook de invloed aan het hof sterk toe. Raspoetin vroeg toestemming om zijn naam te wijzigen, want er woonden twintig andere mensen in het dorp die Raspoetin heetten; tsaar Nicolaas II stemde toe.

Zijn alsmaar toenemende populariteit en unieke status aan het hof waren een bron van jaloezie....De monnik Iliodor en bisschop Hermogen eisten van Raspoetin dat hij berouw toonde voor zijn immorele handelingen, anders zouden ze met een lijst van Raspoetins misdaden naar de tsaar gaan. Raspoetin weigerde en zorgde ervoor dat Iliodor en Hermogen in 1911 gevangengezet werden in een klooster. Uit wraak liet Iliodor de briefwisseling tussen de tsarina en Raspoetin uitlekken aan de pers.[9] In de gepubliceerde brieven verklaarde de tsarina haar afhankelijkheid van Raspoetin en er werd een nieuw onderzoek opgezet naar zijn achtergrond en ideeën. Om escalatie van het conflict te vermijden, ging hij op pelgrimstocht naar het Heilige land....Door zijn grote macht aan het hof en op de Russische politiek en vooral door het feit dat hij zich voor en tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog als pacifist opstelde, werd hij door de Russische adel steeds meer gewantrouwd. Volgens sommigen zou hij een Duits agent zijn, een verhouding hebben met de (van oorsprong Duitse) tsarina en over een duivelse macht beschikken.... Raspoetin werd in de nacht van 29 op 30 december 1916 door prins Felix Joesoepov, het ultra-rechtse doemalid Vladimir Poerisjkevitsj en grootvorst Dimitri Pavlovitsj van Rusland (Romanov), een volle neef van de tsaar, in het paleis van de familie Joesoepov aan de rivier de Mojka te Petrograd vermoord (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grigori_Raspoetin).

Gregory Efimovich Rasputin came from solid peasant stock, but drunkenness, stealing and womanising were activities particularly enjoyed by the dissolute young man.

Rasputin became fascinated by a renegade sect within the Russian Orthodox faith, who believed that the only way to reach God was through sinful actions. Soon, he adopted the robes of a monk, and travelled the country, sinning to his heart's content.

In 1903, the infant heir to the Russian throne, Alexis, was diagnosed with haemophilia. Tsarina Alexandra became desperate to help him and lost faith in doctors.

In St. Petersburg, Rasputin moved in the Russian capital's aristocratic circles, achieving recognition and a small following. Under the recommendation of the Grand Duchess, Rasputin was summoned to appear before Alexandra.

Somehow, Rasputin managed to stop Alexis' bleeding, and gained Nicholas and Alexandra's undivided support.

As the monk's fortunes rose in St. Petersburg, so did the number of his enemies. Rumours circulated about Alexandra's supposed sexual involvement with the monk. During his many drunken parties, Rasputin would boast of his exploits with the Tsarina and her daughters, even claiming that the Tsar was his to command.

Alexandra grew increasingly dependent on Rasputin and, after 1911, several roles within high government were filled by his appointees, allowing him great influence over matters of state. This perceived weakness of the Tsar and Tsarina helped to destroy the general respect for them.

In 1916, a group of aristocrats tried to murder Rasputin. He drank poisoned wine, and ate pastries containing cyanide, but he survived. He was then shot, stabbed repeatedly, and finally drowned in the icy Neva river.

However, the regime’s image continued to be tainted by the scandal. Within three months of Rasputin's death, Tsar Nicholas lost his throne, and the imperial family were imprisoned. Revolution had come (www.history.co.uk/biographies/rasputin).

Careful to maintain his pretence of being a humble if mystically talented peasant while in the royal couple's presence, Rasputin however lost no time in indulging his voracious sexual appetite outside the court. He shortly afterwards hit upon the satisfying discovery that sexual contact with his own body imbued a healing effect upon women.

The Tsar, informed in detail of Rasputin's scandalous conduct, initially dismissed the 'mad monk' from court; however the influence of his wife, Alexandra, ensured his rapid recall. Thereafter both Nicholas and Alexandra declined to give credence to further reports of Rasputin's misbehaviour; indeed, Alexandra positively discouraged criticism of 'our friend'.

Since news of Alexis's condition was not allowed to be made general knowledge the public at large, unaware of Rasputin's chief role as a healer at court, assumed that he was actively seducing Alexandra. Salacious details of his general conduct, fed and (if it were possible) exaggerated by his many ill-wishers, became the subject of public scandal.

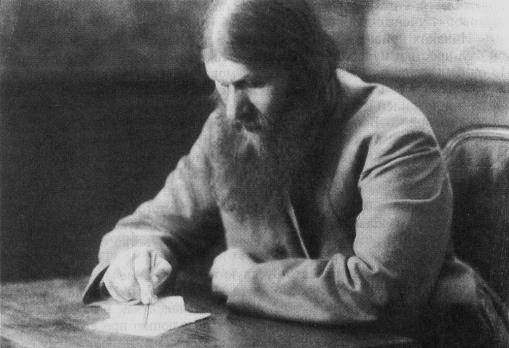

Rasputin's influence continued into wartime. Alexandra sought his opinion on a variety of policy matters. Rasputin, generally ready to offer advice, occasionally offered advice on Russian military strategy, although such advice never proved beneficial.

In one sense Rasputin's presence, while generally damaging public perception of the Romanovs, nevertheless benefited the Tsar. Military calamities were often attributed by the Russian public to Rasputin's baleful influence: as such it therefore deflected direct criticism away from the Tsar himself.

However with the Tsar's decision to take personal command of his army from the front (thereby reliving his uncle, Grand Duke Nikolai, of the role), disaster beckoned. Not only was the Tsar thereafter directly associated with the fruits of his army's efforts (which continued its extended poor run), but in his absence domestic governance of political affairs was effectively left in the hands of the Tsarina and Rasputin (with the Prime Minister, Boris Sturmer, ever willing to defer to the Tsarina's wishes).

With Rasputin offering advice on the appointment (and dismissal) of public and church officials, and rumour spreading that the Tsarina and Rasputin were in the pay of the Germans, a group of nobles at court, led by Felix Yusupov, determined to resolve the appalling damage inflicted by Rasputin upon the monarchy by arranging his murder.

Yusupov invited Rasputin to dine at his home on 29 December 1916 where he was given poisoned wine and cakes. Alarmed at Rasputin's apparent immunity to the poison Yusupov shot him in panic ("A shudder swept over me; my arm grew rigid, I aimed at his heart and pulled the trigger.", Lost Splendor, 1953).

After a brief period of collapse Rasputin recovered and managed to escape into the courtyard, where he was again shot (by another conspirator, Vladimir Purishkevich). Finally, presumably to make quite sure of the matter, Rasputin's body was dropped through a hole in the Neva river, where he finally died by drowning. His corpse was later discovered on the Neva's banks.

As an attempt to salvage the credibility of the monarchy Yusupov's bold move came too late; if anything, the murder of Rasputin removed a buffer between the royal family and their critics: no longer could the nation's ills be attributed to the mad monk who had prophesised his own demise (www.firstworldwar.com/bio/rasputin.htm).

First, Rasputin’s would-be killers gave the monk food and wine laced with cyanide. When he failed to react to the poison, they shot him at close range, leaving him for dead. A short time later, however, Rasputin revived and attempted to escape from the palace grounds, whereupon his assailants shot him again and beat him viciously. Finally, they bound Rasputin, still miraculously alive, and tossed him into a freezing river. His body was discovered several days later and the two main conspirators, Youssupov and Pavlovich were exiled.

Not long after, the Bolshevik Revolution put an end to the imperial regime. Nicholas and Alexandra were murdered, and the long, dark reign of the Romanovs was over (www.history.com/this-day-in-history/rasputin-is-murdered).

Er is bier naar 'm vernoemd...

Old Rasputin van North Coast Brewing

Produced in the tradition of 18th Century English brewers who supplied the court of Russia’s Catherine the Great, Old Rasputin seems to develop a cult following wherever it goes. It’s a rich, intense brew with big complex flavors and a warming finish.

The Old Rasputin brand image is a drawing of Rasputin with a phrase in Russian encircling it—A sincere friend is not born instantly.

Style: Russian Imperial Stout

Color: Black

ABV: 9%

Bitterness: 75 IBUs (www.northcoastbrewing.com/beers/year-round-beers/old-rasputin-russian-imperial-stout/?ao_confirm)

Zoals ik al vertelde in 2013 over Op&Top had brouwerij De Molen een bier: De Molen Disputin - Russian Imperial Stout (11%) is een Russian Imperial Stout die voorheen Rasputin heette: Formerly named "Rasputin," this beer is now labeled as "Disputin" due to a dispute with North Coast over the name. Also has been called "Cease & Desist" (http://beeradvocate.com/beer/profile/11031/41867).

Momenteel drink ik nog een Rasputin (10,4%) met een 202 EBC en 46 EBU. Het bier smaakt romig alcoholerig zacht met een wat wrangbitter afdronk die intrigerend werkt. De geur is zwaar alcolholerig, zonder overdreven zoet of branderig te zijn. Het lijkt totaal niet op een zoetbranderige Gulden Draak om maar wat te noemen. Het was de eerste Imperial Russian Stout van brouwerij de Molen (maar zeker niet de laatste). Het was vernoemd naar de beroemde Rus aan het hof van de Romanovs. Volgens het sommigen is hij persoonlijk verantwoordelijk voor het feit dat tijdens de heerschappij van Tsaar Nicholaas II en Tsarina Alexandra deze stijl zou zijn ontstaan (http://allebrouwerijen.nl/molen-rasputin.html).

Anno 2016 kwam ik 'm tegen bij Burgbieren in Ermelo. Ik probeerde de Rasputin (10,4%) en het smaakte vol. De geur is alcoholerig en doet mij denken aan een barleywine. Het heeft een milde bittere (denk aan pure chocolade) nasmaak. Het bier heeft een beetje en zoetje, maar heeft ook wat mocca in zich verstopt. Het zou een RIS (Russian Imperial Stout) zijn, volgens bovenstaande verhaal. Het bier drinkt makkelijk weg, het heeft een uitnodigend mondgevoel. Het heeft een bittere, alcoholerige, licht moutige, licht zoete smaak.