Op www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/ staan

Important events of 1918 during the fifth and final year of the First World War, including the French Marshall Ferdinand Foch (pictured) being appointed Supreme Allied Commander.

3 March

A peace treaty is signed between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey) at Brest-Litovsk. The treaty marks Russia's final withdrawal from World War I. The humiliating terms of the treaty effectively surrenders one third of Russia's population, half of her industry and 90% of her coal mines. Russia also cedes lands including Poland, Ukraine and Finland, and cash payments are made to release Russian prisoners (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

Russia entered the first world war with the largest army in the world, standing at 1,400,000 soldiers; when fully mobilized the Russian army expanded to over 5,000,000 soldiers (though at the outset of war Russia could not arm all its soldiers, having a supply of 4.6 million rifles) (www.marxists.org/glossary/events/w/ww1/russia.htm).

In the opening months of the war, the Imperial Russian Army attempted an invasion of eastern Prussia in the northwestern theater, only to be beaten back by the Germans after some initial success. At the same time, in the south, they successfully invaded Galicia, defeating the Austro-Hungarian forces there.[8] In Russian Poland, the Germans failed to take Warsaw. But by 1915, the German and Austro-Hungarian armies were on the advance, dealing the Russians heavy casualties in Galicia and in Poland, forcing it to retreat. Grand Duke Nicholas was sacked from his position as the commander-in-chief and replaced by the Tsar himself.[9] Several offensives against the Germans in 1916 failed, including Lake Naroch Offensive and the Baranovichi Offensive. However, General Aleksei Brusilov oversaw a highly successful operation against Austria-Hungary that became known as the Brusilov Offensive, which saw the Russian Army make large gains.[10][11][12] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_Front_(World_War_I)).

Belgians were the first among Great War combattants to make extensive use of armoured cars as a military weapon. During the siege of Antwerp, from mid August to the first week of October 1914, numerous motor vehicles were stripped and rebuilt with armour plating. Machine guns were mounted and even rotating cupolas were fitted. Most vehicles were (re)built by the Minerva Motor Car Company in Antwerp, though other large industrial metal works and manufacturing firms contributed to the war effort.

These armoured vehicles were used for reconnaisance, long distance messaging and for carrying out raids and small scale engagements. Circumstances dictated that the small, outnumbered Belgian Army use these highly mobile armoured cars in guerrilla style hit-and-run engagements against the besieging German army. Not only were they quite effective in conducting raids, blowing bridges and delivering messages to exposed positions, they were extremely photogenic as well, a news editors dream. The British press, playing up the 'Brave Little Belgium' angle in newspapers and magazines, published many photos of Belgian armoured cars in and around Antwerp. (see Minerva Armoured Cars)

After the fall of Antwerp in October 1914 and the retreat to the Yser, the front line stabilised and since a breakthough was not forthcoming, there was little use for a highly mobile armoured car force. The Russian military attaché to the Belgian armed forces suggested that the armoured car force could be of use on the Eastern Front. Following protocol, Czar Nicholas made an official request to King Albert of the Belgians. It was decided to send a force of several hundred Belgians to Russia. Since Belgium and Russia were co-belligerents and not official allies, for legal reasons the Belgian soldiers were to be considered as volunteers in the Russian army.

The Belgian force sailed from Brest on September 22nd 1915 and reached Archangel on October 13, 1915. By way of Petrograd, they were sent to Galicia where they mainly saw action against Austrian forces. The Belgian armoured cars came to be known as effective machine gun destroyers. They continued fighting after the Russian Revolution until the treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed. The Belgian armoured car force was recalled but had a difficult time returning home. The trip back to Archangel being unfeasible, the Belgians, much like the Czech Legion, followed the Trans-Siberian railway, crossed northern China and ultimately arrived in Vladivostok. On April 18th, 1918 they boarded an American vessel, the SS Sheridan and sailed to San Francisco. From there they travelled on a much acclaimed and widely publicized trip through the US and sailed from New York on June 15th 1918, finally reaching Paris two weeks later. Thet were disbanded shortly afterwards (http://histomil.com/viewtopic.php?t=12314).

A Russian officer suggested it and of course King Albert I was always willing to help but the Tsar had to ask first because, since Belgium was a neutral country, the small kingdom and the massive empire were fighting on the same side but not exactly were allies in the strictest sense. Also, because of this, on paper at least, the Belgian troops were volunteers in the Russian Imperial Army rather than officially soldiers of the Belgian army for this special mission. In all there were over 300 men who went with the armored cars, motorcycles and bicycles to the Russian front, over time around 400 men were served as troops rotated out. They saw their biggest battles on the Galician front and their speed and firepower were proven to be very good at eliminating Austrian machine-guns positions. These brave men far from home fought even after the Germans had clearly gained the upper hand and they also kept on fighting and doing their duty even after the 1917 Revolution. It was not until the new Russian government made their own peace with the Germans that the Belgians decided it was time to go home.

That was difficult to do because of the revolutionary forces that viewed the Belgian forces as enemies and they blocked the way to all the major ports. The Belgian forces then because of this had to travel across the whole of Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railway to the Pacific where they took a ship to San Francisco, California and then went by train across the United States, being much celebrated along the way, reaching New York and from there sailed across the Atlantic to finally reach Paris two weeks later. In all, their losses were few, only 16 men during all of their fighting and travels were killed (http://histomil.com/viewtopic.php?t=12314).

The Belgian Expeditionary Corps of Armoured Cars in Russia (French: Corps Expeditionnaire des Autos-Canons-Mitrailleuses Belges en Russie) was a Belgian military formation during the First World War which was sent to Russia to fight the German Army on the Eastern Front. Between late 1915 and 1918, 444 Belgian soldiers served with the unit of whom 16 were killed in action.[1]

As the front line in the west stabilized following the Battle of the Yser, the Belgian army was left with a number of armoured cars that could not be used in the static trench warfare which had emerged along the Belgian-held Yser Front. In early 1915, Tsar Nicholas II formally requested military support from King Albert I and a self-contained unit was formed for service in Russia.[2] As Belgium was not officially an ally of the Russian Empire but a neutral power, the Belgian soldiers in the unit were officially considered as volunteers in the Imperial Russian Army itself.

The first contingent of the Belgian Expeditionary Corps, 333 volunteers equipped with Mors and Peugeot armoured cars, arrived in Archangel in October 1915.[1] The unit fought with distinction in Galicia and was mentioned in the Order of the Day five times.[3]

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the Belgian force remained in Russia until the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk withdrew Russia from the war. After the ceasefire, the unit found itself in hostile territory. As the route north to Murmansk was blocked, the soldiers destroyed their armoured cars to prevent their capture by Bolshevik forces.[3] The unit finally reached the United States through China and the Trans-Siberian railway in June 1918.[1]

A similar, slightly larger British unit, the Armoured Car Expeditionary Force (ACEF), also served in Russia during the same period (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belgian_Expeditionary_Corps_in_Russia).

(Over the Top: Alternative Histories of the First World War Door Spencer Jones,Peter Tsouras; blz. 138) (http://landships.activeboard.com/t4968671/belgian-armoured-cars-in-russia/)

When it first set sail, the Belgian armoured car force numbered 333 Belgians, all volunteers. In Russia 33 Russians joined its ranks. Counting reinforcements and replacements, 444 Belgians passed through the ranks. There were 58 vehicules of which 12 were armoured cars plus 23 motor-bicycles and 120 bicycles. 16 Belgians were killed in action in Russia. Only one armoured car was lost. It was captured by German forces and is said to have been used in Berlin during the insurrections in 1919 (http://histomil.com/viewtopic.php?t=12314).

The Kingdom of Romania entered the war in August 1916. The Entente promised the region of Transylvania (which was part of Austria-Hungary) in return for Romanian support. The Romanian Army invaded Transylvania and had initial successes, but was forced to stop and was pushed back by the Germans and Austro-Hungarians when Bulgaria attacked them in the south. Meanwhile, a revolution occurred in Russia in February 1917 (one of the several causes being the hardships of the war). Tsar Nicholas II was forced to abdicate and a Russian Provisional Government was founded, with Georgy Lvov as its first leader, who was eventually replaced by Alexander Kerensky.

The newly formed Russian Republic continued to fight the war alongside Romania and the rest of the Entente until it was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in October 1917. Kerensky oversaw the July Offensive, which was largely a failure and caused a collapse in the Russian Army. The new government established by the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers, taking it out of the war and making large territorial concessions. Romania was also forced to surrender and signed a similar treaty, though both of the treaties were nullified with the surrender of the Central Powers in November 1918 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_Front_(World_War_I)).

21 March

With 50 divisions now freed by the surrender of Russia, Germany realises that its only chance of victory is to defeat the Allies quickly before the huge human and industrial resources of America are deployed. Germany launches the Ludendorff (or first Spring) Offensive against the British on the Somme.

26 March

The French Marshall Ferdinand Foch is appointed Supreme Allied Commander on the Western Front.

1 April

The Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service are merged to form the Royal Air Force.

9 April

Germany launches a second Spring Offensive, the Battle of the Lys, in the British sector of Armentieres. The front line Portuguese defenders were quickly overrun by overwhelming numbers of German troops. The capture of the Channel supply ports at Calais, Dunkirk and Boulogne could choke the British into defeat (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

In the spring of 1918, Luderndorff ordered a massive German attack on the Western Front. The Spring Offensive was Germany’s attempt to end World War One (www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-one/battles-of-world-war-one/the-german-spring-offensive-of-1918/).

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (Kruszewnia, 9 april 1865 – Tutzing, 20 december 1937) was een Duits generaal en politicus.

In de eerste maanden van de Eerste Wereldoorlog behaalde Ludendorf twee grote overwinningen. In de slag om Luik en de slag bij Tannenberg wist hij respectievelijk het Belgische- en Russische leger grote nederlagen toe te brengen. Zijn benoeming in augustus 1916 tot kwartiermeester-generaal maakte hem (met Paul von Hindenburg) het de facto hoofd en de leidende figuur achter de Duitse oorlogsinspanning tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog.

Dit bleef zo tot de keizer in oktober 1918 zijn ontslag aanvaardde. Dit nadat Ludendorff door een monumentale beslissing zowel het einde van de Eerste Wereldoorlog, alsook de val van het Duitse keizerrijk en de start van de Duitse Novemberrevolutie had ingeluid.

Na zich enige tijd in Zweden te hebben teruggetrokken maakte hij in de loop van 1919 zijn rentree in de Duitse politiek. Hij werd een prominent nationalistisch leider en was een van de architecten van de dolkstootlegende. Zowel in 1920 in Berlijn (Kapp-putsch van Wolfgang Kapp) als in 1923 in München (Bierkellerputsch van Adolf Hitler) speelde Ludendorff een actieve rol bij mislukte pogingen tot staatsgreep met als doel om de Weimarrepubliek te elimineren (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Ludendorff).

The 1918 Spring Offensive or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser's Battle), also known as the Ludendorff Offensive, was a series of German attacks along the Western Front during the First World War, beginning on 21 March 1918, which marked the deepest advances by either side since 1914. The Germans had realised that their only remaining chance of victory was to defeat the Allies before the overwhelming human and matériel resources of the United States could be fully deployed. They also had the temporary advantage in numbers afforded by the nearly 50 divisions freed by the Russian surrender (the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spring_Offensive).

Het Lenteoffensief of de Kaiserschlacht was een combinatie van aanvallen van het Duitse leger tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog in de lente en zomer van 1918. De militaire naam van de eerste operatie was "Operatie Michael". De Duitsers zouden voor de laatste keer alles op alles zetten, deze keer met een nieuwe tactiek.

In 1917 was de situatie voor Duitsland nijpender en nijpender geworden. De poging om de geallieerden met de duikbotenoorlog te verslaan had uiteindelijk een oorlogsverklaring van de machtige Verenigde Staten opgeleverd, de Centrale bondgenoten presteerden weinig of helemaal niets zonder Duitse hulp, en het westfront zat nog steeds muurvast. De Duitse economie en voedselsituatie ging gebukt onder de Britse blokkade. De Russische Revolutie bleek een meevaller: Rusland had het Verdrag van Brest-Litovsk moeten tekenen en was uit de oorlog. De Duitsers konden nu troepen van het oostfront vrijmaken voor een grote aanval in het Westen. Generaal Erich Ludendorff wilde met een combinatie van aanvallen een wig tussen de Fransen en de Britten drijven, waarna de Britten dwars door Noord-Frankrijk de zee in zouden worden gedreven. Dit zou de Franse ineenstorting brengen en de Amerikanen doen afzien van verdere hulp aan de geallieerden. Aldus Ludendorff.

Ludendorff had een aantal offensieven gepland die onderdeel zouden uitmaken van Operatie Michael. Dit waren onder andere:

Mars, een offensief tegen de Britten en Fransen bij de Somme en Arras, en dat een wig tussen de twee legers moest drijven;

Georgette, een offensief in het noorden tegen de Britten in België;

Blücher-Yorck, een offensief tegen de Fransen bij Chemin des Dames;

Friedensturm, een offensief tegen de Fransen richting de Marne en Parijs.

Ludendorff zag in, dat domweg aanvallen gelijkstond aan zelfmoord. Daarom veranderde hij de tactiek. Allereerst koos hij voor de zogenaamde Bruchmüllertactiek, een artilleriebombardement van vijf uur voorafgaand aan het offensief, in verschillende fases. Dit omdat de traditionele dagenlange bombardementen het verrassingseffect bedierven (bijvoorbeeld bij de Slag aan de Somme). Onder dekking van gordijnvuur van de artillerie moesten vervolgens eenheden van de elitestormtroepen, bewapend met automatische geweren en vlammenwerpers, de uiteengereten Britse frontlinie infiltreren, om daarna zo snel mogelijk de Britse artilleriestellingen achter de frontlinie in handen te krijgen. De inname van de grote steunpunten werd aan de infanterie overgelaten, die achter de stormtroepen kwamen. Hierbij werkten artillerie en infanterie beter samen en werd door de stormtroepen meer gebruikgemaakt van de mogelijkheden die het terrein kon bieden: een tactiek die van de Japanners in hun oorlog met Rusland was afgekeken (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenteoffensief).

The massive surprise attack (named Blücher-Yorck after two Prussian generals of the Napoleonic Wars) lasted from 27 May until 4 June 1918[1] and was the first full-scale German offensive following the Lys Offensive in Flanders in April (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Battle_of_the_Aisne).

Op 21 maart 1918 barstten de eerste aanvallen los. De offensieven waren aanvankelijk zeer succesvol. De geallieerde loopgraven werden doorbroken en de Duitse legers waren weer op mars. In twee dagen werden bij de Somme de Britse linies doorbroken en rukten de Duitsers 25 km op. Generaal Haig, de Britse bevelhebber, verzocht om versterkingen, maar de Fransen waren ook bij Parijs aangevallen en Pétain vond het verdedigen van de hoofdstad belangrijker. Ook hier werden de loopgraven aanvankelijk doorbroken. Keizer Wilhelm II was buiten zichzelf van vreugde.

De Duitsers waren met de doorbraak echter niets opgeschoten. De enige opdracht die ze hadden was "oprukken", maar toen ze verder kwamen, kwamen ze ook buiten de dekking van hun eigen artillerie. Bovendien moest de infanterie door het oude slagveld aan de Somme. De oude loopgraven lagen er nog, compleet met mijnen, prikkeldraad en modder. Ook waren veel soldaten ondervoed en dus snel afgeleid: vonden ze een voedseldepot, dan plunderden de soldaten dat en vergaten hun opmars. De Britten hergroepeerden en vingen de aanval bij Arras op, en op 28 maart 1918 was het front weer stabiel. Ludendorff kraaide victorie, de keizer en veel Duitsers geloofden hem. De Duitsers was namelijk gelukt, wat de geallieerden in drie jaar nooit was gelukt: de loopgravenlinie doorbreken. Bovendien was veel terrein verroverd en stonden de Duitsers op sommige punten zelfs verder dan in 1914! (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenteoffensief)

The first few days of the attack were such an overwhelming success, that William II declared March 24th to be a national holiday. Many in Germany assumed that the war was all but over.

However, the Germans experienced one major problem. Their advance had been a major success. But their troops deliberately carried few things except weapons to assist their mobility. The speed of their advance put their supply lines under huge strain. The supply units of the storm troopers simply could not keep up with them and those leading the attack became short of vital supplies that were stuck well back from their positions (www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-one/battles-of-world-war-one/the-german-spring-offensive-of-1918/).

Het was echter een valse victorie. De Britten hadden wel gebied en materieel verloren, maar vormden nog steeds een gesloten front. De gebieden hadden geen enkele strategische waarde (concrete strategische doelen waren ook niet gesteld, het ging slechts om het zo ver mogelijk oprukken) en waren ten koste van veel munitie en mensenlevens veroverd, terwijl de eigen artillerie het niet kon bijbenen. Er heerste een munitietekort. Verblind door dit "succes", zette Ludendorff echter Operatie Michael voort en opende nog meer offensieven. Evenals Operatie Mars dienden deze offensieven echter geen enkel strategisch doel.

Ook deze offensieven vertoonden hetzelfde patroon: een doorbraak gevolgd door een opmars, vervolgens stagnatie. Bij de Tweede slag bij de Marne werden de Duitsers door de Fransen tegengehouden, en deze keer was het geen resultaat van Duitse twijfel, maar van een taaie Franse verdediging en de eerder genoemde tekortkomingen. Ook de offensieven in België en bij Reims liepen vast (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenteoffensief).

The French had suffered over 98,000 casualties and the British around 29,000. German losses were nearly as great, if not slightly heavier. Duchene was sacked by French Commander-in-Chief Philippe Petain for his poor handling of the British and French troops. The Americans had arrived and proven themselves in combat for the first time in the war.

Ludendorff, encouraged by the gains of Blücher-Yorck, launched further offensives culminating in the Second Battle of the Marne (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Battle_of_the_Aisne).

23 April

The Zeebrugge Raid was an attempt by the British Royal Navy to block the Belgium port of Bruges-Zeebrugge. The port was an important base for German U-boats. The raid was only a partial military success but an important propaganda victory for the Allies.

25 May

German U-boats appear in U.S. waters for first time (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

The plan was to sink three old cruisers at the entrance to the German-occupied Belgian port of Bruges-Zeebrugge, which was being used by U-boats. Things didn't go entirely as planned

This WWI mission was one of the first times that a small British special force was used in a lightning strike against the enemy. The plan – conceived and led by Admiral Roger Keyes – was to sink three old cruisers at the entrance to the German-occupied Belgian port of Bruges-Zeebrugge, which was being used by U-boats. Things didn’t go entirely as planned. The Marines who landed came under fierce fire, and the harbour entrance was only blocked for a few days – at a cost of about 200 British dead. However, it was an extraordinarily brave attack and showed what special forces were capable of (www.dailymail.co.uk/home/moslive/article-2199328/Greatest-special-forces-raids-Zeebrugge-Raid-Operation-Entebbe-Paddy-Ashdowns-secret-missions.html).

The Zeebrugge Raid (French: Raid sur Zeebruges; 23 April 1918), was an attempt by the Royal Navy to block the Belgian port of Bruges-Zeebrugge. The British intended to sink obsolete ships in the canal entrance, to prevent German vessels from leaving port. The port was used by the Imperial German Navy as a base for U-boats and light shipping, which were a threat to Allied shipping, especially in the English Channel (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeebrugge_Raid).

In a daring raid on April 23, 1918, the Royal Navy tried to block the entrance to the Belgian port of Zeebrugge, a major submarine base.

The plan was to scuttle ships at the port entrance as the old cruiser HMS Vindictive landed a force of 200 Royal Marines.

But the plan went badly wrong because of heavy German fire. The blockships were sunk in the wrong place and Vindictive was also forced to land the Marines at the wrong spot.

The raiding force suffered more than 580 casualties, including 227 dead. To boost morale at home, the raid was hailed as a major victory, but in reality it was a failure as the canal at the port entrance was blocked for only a few days (http://www.kentonline.co.uk/whats-on/news/daring-but-doomed-12782/).

De aanval op de haven van Zeebrugge (Engels: Zeebrugge Raid) tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog was een Britse aanval op de haven van Zeebrugge op 23 april 1918 met het doel de vaargeul te blokkeren, zodat Duitse U-boten niet meer konden uitvaren. Tegelijkertijd werd ook de haven van Oostende aangevallen.

Met de zeeslag bij Jutland was de Duitse vloot verslagen. Duitsland besloot om de oorlog niet op maar onder de zee voort te zetten als onbeperkte duikbotenoorlog. Hiertegen hadden de Britten toen geen verweer. Duikboten vanuit Wilhelmshaven vormden geen grote bedreiging, omdat ze een dag onderweg waren en langs mijnenvelden moesten. Een poging om de mijnen te vegen was mislukt tijdens de Tweede slag bij Helgoland. Antwerpen was ook geen probleem, omdat het van op het water kon beschoten worden. De duikbootbasis van Brugge lag te ver landinwaarts om ze vanuit zee te beschieten. Ook ze vanuit de lucht bombarderen was in die tijd te moeilijk. De duikboten voeren langs de kanalen naar Zeebrugge of Oostende en zo naar zee, waar ze Britse schepen aanvielen.... De aanval werd op 11 april en op 14 april afgeblazen wegens slecht weer. De motorboot HMS CMB 33 was daarbij gestrand in Duits gebied. De bevelvoerder had - tegen alle instructies in - de aanvalsplannen meegenomen die in handen van de Duitsers waren gevallen.

In de haven van Zeebrugge waren bunkers en verstevigingen aangelegd en er was zware artillerie op de havendam. De toegang van de haven zelf werd gedeeltelijk geblokkeerd door de verankering van een viertal aken.

Op 22 april 1918 nam admiraal Keyes het bevel over een vloot van 168 schepen en een troepenmacht van 1800 man. De aanval begon op 23 april 1918 vanuit Dover, Duinkerken en het Zwin.... De aanval op de haven van Oostende die tegelijkertijd plaatsvond was ook een mislukking. Ook een tweede aanval op Oostende in mei mislukte. Duitse duikboten konden nog altijd vanuit Brugge naar Zeebrugge of Oostende de zee op, totdat in oktober 1918 de Britse landmacht het terrein veroverde. De gezonken wrakken werden pas in 1921 geborgen.

De aanval op Zeebrugge wordt door de Britten ieder jaar herdacht op 23 april, Saint-George's Day. De operatie stond model voor Operatie Chariot, een soortgelijke aanval op Saint-Nazaire tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aanval_op_de_haven_van_Zeebrugge).

The Zeebrugge Raid, 1918 Zeebrugge was an outlet for German U-boats and destroyers based up the canal at Bruges, and the British planned to sink three old cruisers Iphegenia, Intrepid and Thetis, in the channel to block it. These would have to pass a long harbour mole (a causeway or pier), with a battery at the end, before they were scuttled. It was decided therefore to storm the mole using another old cruiser, HMS Vindictive, and two Mersey ferries, Daffodil and Iris II, modified as assault vessels. Two old submarines were to be used as explosive charges, under the viaduct connecting the mole to the shore.

The attack went in on the night of 22-23 April, under the command of Commodore Roger Keyes. Vindictive was heavily hit on the approach, and came alongside in the wrong place. Despite much bravery by the landing party, the battery remained in action. One submarine did succeed in blowing up the viaduct, but the first block ship was badly hit and forced to ground before reaching the canal entrance. Only two (Ipheginia and Intrepid) were sunk in place.

Much was made of the raid. Keyes was knighted, and 11 Victoria Crosses were awarded. The Germans, however, made a new channel round the two ships, and within two days their submarines were able to transit Zeebrugge. Destroyers were able to do so by mid-May (www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwone/war_sea_gallery_06.shtml).

(www.armchairgeneral.com/cdg46-zeebrugge-raid-1918.htm)

(https://raymondshirley.blogspot.nl/2016/02/the-british-naval-raid-on-mole-at.html)

27 May

The Third German Spring Offensive, Third Battle of the Aisne, begins in the French sector along Chemin des Dames. The main objective of the German's was to split French and British forces in an attempt to gain a quick victory before American troops were deployed in greater numbers on the battlefields of Europe (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

Whilst the first two battles of the Aisne were conducted by Allied forces, predominantly French, against the German army in France, the Third Battle of Aisne, from 27 May-6 June 1918, comprised the final large-scale German attempt to win the war before the arrival of the U.S. Army in France, and followed the Lys Offensive in Flanders.

The focus of the offensive was the Chemin des Dames Ridge, held by the Germans upon their retreat from the Marne in September 1914 until their ejection, at huge cost to the French, during the Nivelle Offensive, also known as the Second Battle of the Aisne, in April 1917.

Erich Ludendorff, although subservient to Paul von Hindenburg within the German Third Supreme Command, effectively dictated the planning and execution of the German war effort. He determined to reclaim the Chemin des Dames Ridge from the French with the launch of a massed concentrated surprise attack. In so doing he anticipated that the French would divert forces from Flanders to the Aisne, leaving him to renew his offensive further north, where he believed the war could be won.

At the time of the offensive the front line of the Chemin des Dames was held by four divisions of the British IX Corps, ironically sent from Flanders in early May in order to recuperate (www.firstworldwar.com/battles/aisne3.htm).

Vaak wordt het mislukken van Operatie Michael toegeschreven aan de snelle komst van duizenden Amerikaanse troepen die de Duitse aanval na de doorbraak achter de linies opvingen en terugdreven. De Amerikanen waren echter nog maar net begonnen met de opbouw van hun landleger, en bleven nog ver achter in materieel. Aanvankelijk opereerden zij zelfs niet op eigen titel, maar in Britse of Franse divisies of legers. Ook moest artillerie geleend worden, omdat ze die zelf niet hadden. Ten slotte hadden de Amerikanen absoluut niet de ervaring die hun Duitse tegenstanders en Brits-Franse bondgenoten na bijna vier jaar oorlog wel hadden. Het zou daarom overdreven zijn de geallieerde overwinning enkel aan hen toe te schrijven.

Wel was de deelname van de Amerikanen van psychologische waarde. De Duitsers zagen de dreiging die uitging van een natie met 90 miljoen inwoners, een oppervlakte van miljoenen vierkante kilometer, ongeschonden fabrieken die na verloop van tijd tienduizenden kanonnen zouden kunnen produceren. De VS bezat daarbij één van de grootste marines ter wereld. Militaire kopstukken als Ludendorff beseften dat de tijd in Duitslands nadeel werkte, aangezien de eerder genoemde gebreken dan stuk voor stuk konden worden opgelost. Het was ook de reden voor de Kaiserschlacht: Amerika mocht niet aan de oorlog deel gaan nemen, althans niet actief. Voor de Amerikanen klaar waren, moesten de Britten de oorlog worden uitgeslagen, en daarna de Fransen (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenteoffensief).

28 May

U.S. forces, some 4,000 troops, are victorious in their first major action of the war at the Battle of Cantigny (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

America entered World War One on April 6th, 1917. Up to that date, America had tried to keep out of World War One – though she had traded with nations involved in the war – but unrestricted submarine warfare, introduced by the Germans on January 9th, 1917, was the primary issue that caused Woodrow Wilson to ask Congress to declare war on Germany on April 2nd. Four days later, America joined World War One on the side of the Allies (www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-one/america-and-world-war-one/).

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson went before a joint session of Congress to request a declaration of war against Germany. Wilson cited Germany’s violation of its pledge to suspend unrestricted submarine warfare in the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean, as well as its attempts to entice Mexico into an alliance against the United States, as his reasons for declaring war. On April 4, 1917, the U.S. Senate voted in support of the measure to declare war on Germany. The House concurred two days later. The United States later declared war on German ally Austria-Hungary on December 7, 1917 (https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/wwi).

Germany’s resumption of submarine attacks on passenger and merchant ships in 1917 became the primary motivation behind Wilson’s decision to lead the United States into World War I. Following the sinking of an unarmed French boat, the Sussex, in the English Channel in March 1916, Wilson threatened to sever diplomatic relations with Germany unless the German Government refrained from attacking all passenger ships and allowed the crews of enemy merchant vessels to abandon their ships prior to any attack. On May 4, 1916, the German Government accepted these terms and conditions in what came to be known as the “Sussex pledge.”

By January 1917, however, the situation in Germany had changed. During a wartime conference that month, representatives from the German Navy convinced the military leadership and Kaiser Wilhelm II that a resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare could help defeat Great Britain within five months.

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg protested this decision, believing that resuming submarine warfare would draw the United States into the war on behalf of the Allies. This, he argued, would lead to the defeat of Germany. Despite these warnings, the German Government decided to resume unrestricted submarine attacks on all Allied and neutral shipping within prescribed war zones, reckoning that German submarines would end the war long before the first U.S. troopships landed in Europe. Accordingly, on January 31, 1917, German Ambassador to the United States Count Johann von Bernstorff presented U.S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing a note declaring Germany’s intention to restart unrestricted submarine warfare the following day (https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/wwi).

by 1917, the continued submarine attacks on U.S. merchant and passenger ships, and the “Zimmermann Telegram’s” implied threat of a German attack on the United States, swayed U.S. public opinion in support of a declaration of war. Furthermore, international law stipulated that the placing of U.S. naval personnel on civilian ships to protect them from German submarines already constituted an act of war against Germany. Finally, the Germans, by their actions, had demonstrated that they had no interest in seeking a peaceful end to the conflict. These reasons all contributed to President Wilson’s decision to ask Congress for a declaration of war against Germany. They also encouraged Congress to grant Wilson’s request and formally declare war on Germany (https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/wwi).

The American entry into World War I came in April 1917, after two and a half years of efforts by President Woodrow Wilson to keep the United States neutral during the war. Apart from an Anglophile element supporting the British, American public opinion went along with neutrality at first ... Wilson asked Congress for "a war to end all wars" that would "make the world safe for democracy", and Congress voted to declare war on Germany on April 6, 1917.[3] The same day, the U.S. declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[4][5](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_entry_into_World_War_I).

By 1916 a new factor was emerging—a sense of national self-interest and American nationalism. The unbelievable casualty figures in Europe were sobering—two vast battles caused over one million casualties each. Clearly this war would be a decisive episode in the history of the world. Every American effort to find a peaceful solution was frustrated.

...

The very weakness of American military power encouraged Berlin to start its unrestricted submarine attacks in 1917. It knew this meant war with America, but it could discount the immediate risk because the U.S. Army was negligible and the new warships would not be at sea until 1919 by which time the war would be over, with Germany victorious. The notion that armaments led to war was turned on its head: refusal to arm in 1916 led to war in 1917.

Size of military[edit]

Americans felt an increasing need for a military that could command respect; as one editor put it, "The best thing about a large army and a strong navy is that they make it so much easier to say just what we want to say in our diplomatic correspondence." Berlin thus far had backed down and apologized when Washington was angry, thus boosting American self-confidence. America's rights and America's honor increasingly came into focus. The slogan "Peace" gave way to "Peace with Honor". The Army remained unpopular, however. A recruiter in Indianapolis noted that, "The people here do not take the right attitude towards army life as a career, and if a man joins from here he often tries to go out on the quiet". The Preparedness movement used its easy access to the mass media to demonstrate that the War Department had no plans, no equipment, little training, no reserves, a laughable National Guard, and a wholly inadequate organization for war. Motion pictures like The Birth of a Nation (1915) and The Battle Cry of Peace (1915) depicted invasions of the American homeland that demanded action.[81]

...

Historians such as Ernest R. May have approached the process of American entry into the war as a study in how public opinion changed radically in three years' time. In 1914 most Americans called for neutrality, seeing the war a dreadful mistake and were determined to stay out. By 1917 the same public felt just as strongly that going to war was both necessary and wise. Military leaders had little to say during this debate, and military considerations were seldom raised. The decisive questions dealt with morality and visions of the future. The prevailing attitude was that America possessed a superior moral position as the only great nation devoted to the principles of freedom and democracy. By staying aloof from the squabbles of reactionary empires, it could preserve those ideals—sooner or later the rest of the world would come to appreciate and adopt them. In 1917 this very long-run program faced the severe danger that in the short run powerful forces adverse to democracy and freedom would triumph.

...

In 1917 Wilson won the support of most of the moralists by proclaiming "a war to make the world safe for democracy." If they truly believed in their ideals, he explained, now was the time to fight. The question then became whether Americans would fight for what they deeply believed in, and the answer turned out to be a resounding "Yes".[92]

Antiwar activists at the time and in the 1930s, alleged that beneath the veneer of moralism and idealism there must have been ulterior motives. Some suggested a conspiracy on the part of New York City bankers holding $3 billion of war loans to the Allies, or steel and chemical firms selling munitions to the Allies.[93] The interpretation was popular among left-wing Progressives (led by Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin) and among the "agrarian" wing of the Democratic party—including the chairman of the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee of the House. He strenuously opposed war, and when it came he rewrote the tax laws to make sure the rich paid the most. (In the 1930s neutrality laws were passed to prevent financial entanglements from dragging the nation into a war.) In 1915, Bryan thought that Wilson's pro-British sentiments had distorted his policies, so he became the first Secretary of State ever to resign in protest.[94]

However, historian Harold C. Syrett argues that business supported neutrality.[95] Other historians state that the pro-war element was animated not by profit but by disgust with what Germany actually did, especially in Belgium, and the threat it represented to American ideals. Belgium kept the public's sympathy as the Germans executed civilians,[96] and English nurse Edith Cavell. American engineer Herbert Hoover led a private relief effort that won wide support. Compounding the Belgium atrocities were new weapons that Americans found repugnant, like poison gas and the aerial bombardment of innocent civilians as Zeppelins dropped bombs on London.[91] Even anti-war spokesmen did not claim that Germany was innocent, and pro-German scripts were poorly received.[97] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_entry_into_World_War_I)

Cambrai, 20 November – 4 December 1917[edit]

15 July

The final phase of the great German spring push, the Second Battle of Marne begins. The heavy toll on the German Army from the previous Spring Offences was beginning to show, with depleted and exhausted troops (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

In particular, the German 18th Army had been spectacularly successful. It had advanced to Amiens and threatened the city. However, rather than use the 18th Army to assist other units moving forward so that the Germans could consolidate their advance, Luderndorff ordered the 18th Army to advance on Amiens as he believed the fall of the city would be a devastating blow to the Allies. In this Luderndorff was correct. Amiens was the major rail centre for the Allies in the region and its loss would have been a disaster. However, many believed that the 18th Army could have been more positively used if it had supported other units of the German army as they advanced and then moved on to Amiens. The 18th Army found that it ran out of supplies as it advanced. Horses, that should have been used in the advance on Amiens, were killed for their meat. Therefore, the mobility of the 18th Army was reduced and the loss of such transport was to be vital.

As the Germans advanced to Amiens, they went via Albert. Here the German troops found shops filled with all types of food. Such was their hunger and desperation for food that looting took place and the discipline that had started with the attack on March 21st soon disappeared. The advance all but stopped in Albert and the attack on Amiens imploded.

...

Neither Hindenburg or Luderndorff could face the inevitable. By June 1918, the German Army had been severely weakened by the large number of casualties it had suffered. Then on July 15th 1918, Luderndorff ordered the last offensive by the German Army in World War One. It was a disaster. The Germans advanced two miles into land held by the Allies but their losses were huge. The French Army let the Germans advance knowing that their supply lines were stretched to the limit. Then the French hit back on the Marne and a massive French counter-attack took place. Between March and July 1918, the Germans lost one million men (www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-one/battles-of-world-war-one/the-german-spring-offensive-of-1918/).

Het mislukken van de Kaiserschlacht was daarom ook niet alleen militair-strategisch een grote domper door het ten koste van grote offers veroveren van grote stukken land. Ook moreel was het dat, hoewel aanvankelijk slechts kopstukken als Ludendorff dit konden weten. Nu zouden immers de Amerikanen komen, en tegen de gecombineerde kracht van Groot-Brittannië, Frankrijk en de VS zou Duitsland niet zijn opgewassen. De jongens in het veld zagen dat aanvankelijk nog niet in, aangezien ze net kilometers waren opgerukt. De eigen bevolking werd door de censuur en overdreven berichten zelfs volledig in het ongewisse gelaten (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenteoffensief).

16 July

The former Russian Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, and children, are murdered by the Bolsheviks (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

Dus de deelname aan de eerste wereldoorlog was voor het Democratische Amerika, beter dan voor de Russische Tsaar...

18 July

The Allies counterattack against German forces, seizing the initiative on the Western Front.

8 Aug

Start of the Battle of Amiens, the opening phase of the Allied Hundred Days Offensive, that would ultimately lead to the end of World War I. Allied armoured divisions smash through the once impregnable German trenches. Erich Ludendorff calls it "the black day of the German Army."

15 Sept

Start of an Allied offensive against Bulgarian forces. The Vardar Offensive would last little over a week with Bulgaria eventually signing an armistice and exiting the war. Bulgaria's King Ferdinand would abdicate shortly afterwards (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

De tegenaanval kon niet lang uitblijven. Aanvankelijk vielen de Fransen aan, daarna ook de Britten. Het bezette terrein ging verloren. Ook zij hadden geleerd, en hadden tactische hervormingen doorgevoerd. Hun tactiek was op de Duitse gebaseerd, maar men liet de infanterie niet verder oprukken dan het bereik van de eigen artillerie. Ook was het schietpatroon veranderd: eerst werden de vijandelijke kanonnen uitgeschakeld door artilleriegranaten, daarna werden de vijandelijke kanonniers uitgeschakeld met gifgas. Dit nekte de Duitsers, die aan steeds meer zaken gebrek kregen en steeds verder werden teruggedreven. Op 8 augustus 1918 lanceerden de geallieerden een massale aanval met 400 tanks: Ludendorff sprak over een 'Zwarte Dag' voor het Duitse Leger. Van de overige geplande Duitse aanvallen kwam niets meer.

De tegenaanval was rampzalig voor de Duitsers. Ze verloren steeds meer terrein en ook de discipline begon te breken. De Kaiserschlacht was in feite een gok geweest. Ludendorff had verloren en was zijn inzet kwijtgeraakt. De tegenaanval was één van de factoren die (samen met o.a. de blokkade en het wegvallen van de bondgenoten) leidde tot de Duitse ineenstorting in november 1918. Ludendorff schoof echter de verantwoordelijkheid voor dit alles behendig af op de nieuwe linkse republikeinse regering, waarmee de dolkstootlegende was geboren (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lenteoffensief).

In september 1918, na het mislukte Duitse voorjaarsoffensief in Frankrijk, ontsloeg de keizer Von Hertling en benoemde Max van Baden, een liberaal, tot rijkskanselier. De OHL werd op die manier een zware klap toegebracht omdat Badens voornaamste taak was een wapenstilstand te sluiten met de Entente-mogendheden. Toch steunden Hindenburg en Ludendorff Von Badens wapenstilstandsplannen. Ludendorff berekende dat het Duitse leger tijdens de duur van een wapenstilstand kon hergroeperen en in het voorjaar van 1919 opnieuw in de aanval kon gaan. Zover kwam het echter niet: De overspannen Ludendorff werd in oktober 1918 door keizer Wilhelm II ontslagen en vervanger door generaal Wilhelm Groener. Ludendorff vluchtte vermomd naar Zweden, maar keerde in 1919 naar Duitsland terug.

Ludendorff verbond zich na zijn terugkeer aan de extreemrechtse Nationale Vereniging, waar ook Wolfgang Kapp lid van was. In 1920 pleegde de groep rondom Kapp een mislukte staatsgreep om de socialistische regering omver te werpen.

In de jaren 1920-1924 werkte Ludendorff nauw samen met Adolf Hitler. Ludendorff speelde een rol tijdens de zogenaamde Bierkellerputsch in München van Hitler, toen de laatste op 8 november 1923, via ondemocratische middelen, de macht probeerde te grijpen. Deze coup werd echter nog diezelfde dag afgeslagen door de Münchense politie en de Reichswehr. Mocht de coup geslaagd zijn dan was Ludendorff rijksminister van Defensie geworden en waren Hitler en Ludendorff naar Berlijn opgetrokken om daar de macht te grijpen.

Na de couppoging werden zowel Ludendorff als Hitler berecht. Wegens zijn rol tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog werd Ludendorff vrijgesproken, Hitler zat echter anderhalf jaar vast in de gevangenis van Landsberg. Ludendorff was woedend over zijn vrijspraak.

Van 1924 tot 1928 was Ludendorff lid van de Rijksdag voor de nazi-partij. In 1925 had Ludendorff zich op aandringen van Hitler presidentskandidaat gesteld. Ludendorff, blind door zijn minachting voor Hitler, dacht dat deze nu eindelijk eens had begrepen, dat hij, de oorlogsheld, het boegbeeld van de NSDAP was. Ludendorff kreeg nog geen procent van het electoraat achter zich en leed smadelijk gezichtsverlies, ook in eigen kring. Hitler had zich wederom van een concurrent ontdaan (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Ludendorff).

19 Sept

The British begin an offensive against Turkish forces in Palestine, the Battle of Megiddo. The battle would prove to be the final victory of British General Edmund Allenby's conquest of Palestine. Unlike most other offences of World War I, Allenby's campaigns had succeeded with relatively little cost.

26 Sept

The Meuse-Argonne offensive begins, this will be the last Franco-American campaign of the war. It was during this battle that Corporal (later Sergeant) Alvin York made his famous capture of 132 German prisoners (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

4 Oct

Germany asks the Allies for an armistice.

mid Oct

The Allies have taken control of almost all of German-occupied France and part of Belgium.

21 Oct

Germany ceases its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare.

30 Oct

After refusing orders to put to sea in a bid to launch a final suicide attack on the British Royal Navy, sailors of the German Navy mutiny at the port of Kiel,

After being forced back by Allied troops, Turkey requests an armistice.

3 Nov

Following the fall of Trieste, Austro-Hungary concludes an armistice with the Allies.

7 Nov

Germany begins negotiations for an armistice with the Allies in Ferdinand Foch's railway carriage headquarters at Compiegne.

9 Nov

The German Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicates.

11 Nov

At the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, in the French town of Redonthes, Germany signs an armistice with the Allies - the official date of the end of World War One.

Signing of the armistice with Germany on 11 November in a railroad carriage at Compiègne.

Signing of the armistice with Germany on 11 November in a railroad carriage at Compiègne (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

Post-war 1919

With the war now over the Allies squabble as to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. Germany is plagued by chaos and violence as Communists attempt to seize power.

12 Jan

Diplomats from more than 30 countries met at the Paris Peace Conference in an attempt to form a lasting peace throughout the world.

7 May

A draft copy of the Treaty of Versailles is submitted to the German delegation.

21 June

After waiting for the British fleet to leave its base on exercise, Rear Admiral Ludvig von Reuter, the officer in command of the 74 interned German Navy ships being held at Scapa Flow, gave the order to scuttle his ships to prevent them falling into British hands. Nine German sailors were shot as they attempted to scuttle their ship, the last casualties of the First World War (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

28 June

Exactly five years after the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Treaty of Versailles is signed between the Allies and Germany at Versailles, officially ending the Great War. Many people in France and Britain were appalled that there was to be no trial for the German Kaiser or the other war leaders of the Central Powers.

10 Sept

Treaty of St Germain-en-Laye signed between the Allies and Austria.

4 June 1920

Treaty of Trianon signed between the Allies and Hungary.

24 July 1923

Treaty of Lausanne signed between the Allies and Turkey (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

Subsequent investigations revealed that on the last day of World War I, between the beginning of the armistice negotiations in the railroad cars encampment at the Compiegne Forest, French commander-in-chief Marshal Foch refused to accede to the German negotiators' immediate request to declare a ceasefire or truce so that there would be no more useless waste of lives among the common soldiers. By not declaring a truce even between the signing of the documents for the Armistice and its entry into force, "at the eleventh hour, at the eleventh day and the eleventh month", about 11,000 additional men were wounded or killed - far more than usual, according to the military statistics.[12] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Gunther)

George Edwin Ellison (1878 – 11 November 1918) was the last British soldier to be killed in action during the First World War. He died at 0930 hours (90 minutes before the armistice came into effect) whilst on a patrol on the outskirts of Mons, Belgium.

Ellison, ... is buried in the St Symphorien Military Cemetery, just southeast of Mons.[1] Coincidentally, and in large part due to Mons being lost in the very opening stages of the war and regained at the very end (from the British perspective), his grave faces that of John Parr, the first British soldier killed during the Great War.[2][3] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Edwin_Ellison) (While Parr is believed to be the first Commonwealth soldier killed in action, several soldiers had been killed by friendly fire and accidental shooting after the declaration of war but before troops were sent overseas, starting with Cpl Arthur Rawson on 9 August 1914.[10] Even earlier, on 6 August 1914, the cruiser HMS Amphion (1911) hit a German mine and sank, killing about 150 sailors. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Parr_(British_Army_soldier))

Private George Lawrence Price (Regimental Number: 256265) (December 15, 1892 – November 11, 1918) was a Canadian soldier. He is traditionally recognized as the last soldier of the British Empire to be killed during the First World War.

The 28th Battalion had orders for November 11 to advance from Frameries (South of Mons) and continue to the village of Havre, securing all the bridges on the Canal du Centre. The battalion advanced rapidly staring at 4:00 a.m., pushing back light German resistance and they reached their position along the canal facing Ville-sur-Haine by 9:00 a.m. where the battalion received a message that all hostilities would cease at 11:00 a.m.[1] Price and fellow soldier Art Goodworthy were worried that the battalion's position on the open canal bank was exposed to German positions on the opposite side of the canal where they could see bricks had been knocked out from house dormers to create firing positions. According to Goodworthy, they decided on their own initiative to take a patrol of five men across the bridge to search the houses. Reaching the houses and checking them one by one, they discovered German soldiers mounting machine guns along a brick wall overlooking the canal. The Germans opened fire on the patrol with heavy machine gun fire but the Canadians were protected by the brick walls of one of the houses. Aware that they had been discovered and outflanked, the Germans began to retreat.[2] A Belgian family in one of the houses warned the Canadians to be careful as they followed the retreating Germans. George Price was fatally shot in the chest by a German sniper[3] as he stepped out of the house into the street. He was pulled into one of the houses and treated by a young Belgian nurse who ran across the street to help, but died a minute later at 10:58 a.m., November 11, 1918. His death was just two minutes before the armistice ceasefire, that ended the war, came into effect at 11 a.m.[4] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Lawrence_Price)

Henry Nicholas John Gunther (June 6, 1895 – November 11, 1918) was an American soldier and the last soldier of any of the belligerents to be killed during World War I.[1][2][3] He was killed at 10:59 a.m., one minute before the Armistice was to take effect at 11 a.m.[2][4][5]

Being of recent German-American heritage, Gunther did not automatically enlist in the armed forces as many others did soon after the War was declared in April 1917. In September 1917, he was drafted and quickly assigned to the 313th Regiment, nicknamed "Baltimore's Own;" it was part of the larger 157th Brigade of the 79th Infantry Division. Promoted as a supply sergeant, he was responsible for clothing in his military unit, and arrived in France in July 1918 as part of the incoming American Expeditionary Forces. A critical letter home, in which he reported on the "miserable conditions" at the front and advised a friend to try anything to avoid being drafted, was intercepted by the Army postal censor. As a result, he was demoted from sergeant back down to a private.[3][5][7]

Gunther's unit, Company 'A', arrived at the Western Front on September 12, 1918. Like all Allied units on the front of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, it was still embroiled in fighting on the morning of November 11.[9] The Armistice with Germany was signed by 5:00 a.m., local time, but it would only come into force at 11:00 a.m. Gunther's squad approached a roadblock of two German machine guns in the village of Chaumont-devant-Damvillers near Meuse, in Lorraine. Gunther got up, against the orders of his close friend and now sergeant, Ernest Powell, and charged with his bayonet. The German soldiers, already aware of the Armistice that would take effect in one minute, tried to wave Gunther off. He kept going and fired "a shot or two".[3] When he got too close to the machine guns, he was shot in a short burst of automatic fire and killed instantly.[5][10] The writer James M. Cain, then a reporter for the local daily newspaper, The Sun, interviewed Gunther's comrades afterward and wrote that "Gunther brooded a great deal over his recent reduction in rank, and became obsessed with a determination to make good before his officers and fellow soldiers."[3]...

American Expeditionary Forces commanding General John J. Pershing's "Order of The Day" on the following day specifically mentioned Gunther as the last American killed in the war.[10] The Army posthumously restored his rank of sergeant and awarded him a Divisional Citation for Gallantry in Action and the Distinguished Service Cross.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Gunther)

Sgt. Henry Gunther: Was Last American Death of WWI Hero or Victim?

He was the last American killed on the battlefields of World War I, felled by a German bullet just one minute before the armistice. But almost a century later, the circumstances of Sgt. Henry Gunther's death remain a matter of debate among historians.

Was he a brave hero who charged into an ambush by German soldiers in the final minutes of of the Great War? The senseless victim of military commanders who kept the fight up hours after a cease-fire was signed? Or a conflicted warrior with something to prove who signed his own death warrant?

A U.S. Army citation states that, on Nov. 11, 1918, during the Battle of the Argonne Forest, Gunther’s unit — Alpha Company, 313th Regiment, 79th Infantry Division — ran into a German ambush near the French town of Chaumont-devant-Damvillers, north of Verdun.

At the same time, a message had arrived with word that the war would be over within the hour. That’s when Gunther — pinned down by enemy fire and visibly angry — bolted, with bayonet fixed, and charged the German machine-gun nest. At least one bullet shattered his head. It was 10:59 a.m.

Gen John Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, ordered that Gunther be named the last American to die on the battlefield.

... But investigative reporting over the years painted a more nuanced picture, one that suggests Gunther’s final heroic "charge" was as much about slaying his own demons.

Of German descent, he and his family had become targets of growing anti-German sentiment. ....he had just been busted in rank from sergeant down to private, according to a contemporary Baltimore Sun reporter, James Cain, who interviewed many of Gunther’s platoon mates. (Gunther’s rank was posthumously reinstated).

Apparently, a letter he’d written to a friend bashing Army life and warning him against enlisting made it into the hands of the U.S. military censors. As Cain wrote at the time, "He thought himself suspected of being a German sympathizer. The regiment went into action a few days after he was demoted and from the start he displayed the most unusual willingness to expose himself to all sorts of risk."

Meanwhile, eyewitnesses described the so-called German "ambush" more as warning shots fired overhead. Stunned German soldiers were said to have yelled at Gunther in broken English to stop — that the war was over — but to no avail.

"Gunther still must have been fired by a desire to demonstrate, even at the last minute, that he was courageous and all-American," Cain wrote (www.nbcnews.com/news/world/sgt-henry-gunther-was-last-american-death-wwi-hero-or-n245056).

No war in history attracts more controversy and myth than World War One.

For the soldiers who fought it was in some ways better than previous conflicts, and in some ways worse.

By setting it apart as uniquely awful we are blinding ourselves to the reality of not just WW1 but war in general.

Most soldiers died

In the UK around six million men were mobilised, and of those just over 700,000 were killed. That's around 11.5%.

In fact, as a British soldier you were more likely to die during the Crimean War (1853-56) than in WW1 (www.bbc.com/news/magazine-25776836).

The Treaty of Versailles was extremely harsh

The Treaty of Versailles confiscated 10% of Germany's territory but left it the largest, richest nation in central Europe.

It was largely unoccupied and financial reparations were linked to its ability to pay, which mostly went unenforced anyway.

The treaty was notably less harsh than treaties that ended the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War and World War Two. The German victors in the former annexed large chunks of two rich French provinces, part of France for between 200 and 300 years, and home to most of French iron ore production, as well as presenting France with a massive bill for immediate payment ... Versailles was not harsh but was portrayed as such by Hitler, who sought to create a tidal wave of anti-Versailles sentiment on which he could then ride into power.(http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-25776836).

Drawing Borders after the War[edit]

Poland[edit]

The creation of a free and Independent Poland was one of Wilson’s fourteen points. At the end of the 18th century the state of Poland was broken apart by Prussia, Russia, and Austria. During the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, the Commission on Polish Affairs was created which recommended there be a passageway across West Prussia and Posen, in order to give Poland access to the Baltic through the port of Danzig at the mouth of the Vistula River. The creation of the state of Poland would cut off 1.5 million Germans in East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Poland also received Upper Silesia. British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon proposed Poland’s eastern border with Russia. Neither the Soviet Russians nor the Polish were happy with the demarcation of the border.[78]

Czechoslovakia[edit]

Czechoslovakia was created through the merging of the Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia, previously under Austrian rule, united with Slovakia and Ruthenia, which were part of Hungary. Although these groups had many differences between them, they believed that together they would create a stronger state. The new country was a multi-ethnic state. The population consisted of Czechs (51%), Slovaks (16%), Germans (22%), Hungarians (5%) and Rusyns (4%).[79] Many of the Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians and Poles[80] and some Slovaks, felt oppressed because the political elite did not generally allow political autonomy for minority ethnic groups. The state proclaimed the official ideology that there are no Czechs and Slovaks, but only one nation of Czechoslovaks (see Czechoslovakism), to the disagreement of Slovaks and other ethnic groups. Once a unified Czechoslovakia was restored after World War II the conflict between the Czechs and the Slovaks surfaced again.

Yugoslavia[edit]

Initially Yugoslavia began as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The name was changed to Yugoslavia in 1929. The State secured its territory at the Paris peace talks after the end of the war. The state suffered from many internal problems because of the many diverse cultures and languages within the state. Yugoslavia was divided on national, linguistic, economic, and religious lines.[78]

Romania[edit]

The state of Romania was enlarged greatly after the war. As a result of the Paris peace conference Romania kept the Dobrudja and Transylvania. Between the states of Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Romania an alliance was formed. They worked together on matters of foreign policy in order to prevent a Habsburg restoration.[78]

Austria[edit]

The state of Austria lost a lot of its territory as a result of the war. Austria evolved into a smaller state with a small homogenous population of 6.5 million people. The states that were formed around Austria feared the return of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and put measures into place to prevent it from re-forming.[78]

Hungary[edit]

After the war Hungary lost 65 percent of its pre-war territory. The loss of territory was similar to that of Austria after the breaking up the Austria-Hungary territory. They lost the territories of Transylvania, Slovakia, Croatia, Slavonia, Syrmia, and Banat.[78] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_Front_(World_War_I))

Important events of 1918 during the fifth and final year of the First World War, including the French Marshall Ferdinand Foch (pictured) being appointed Supreme Allied Commander.

3 March

A peace treaty is signed between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey) at Brest-Litovsk. The treaty marks Russia's final withdrawal from World War I. The humiliating terms of the treaty effectively surrenders one third of Russia's population, half of her industry and 90% of her coal mines. Russia also cedes lands including Poland, Ukraine and Finland, and cash payments are made to release Russian prisoners (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

Russia entered the first world war with the largest army in the world, standing at 1,400,000 soldiers; when fully mobilized the Russian army expanded to over 5,000,000 soldiers (though at the outset of war Russia could not arm all its soldiers, having a supply of 4.6 million rifles) (www.marxists.org/glossary/events/w/ww1/russia.htm).

Hoe begon de eerste wereldoorlog ook alweer?

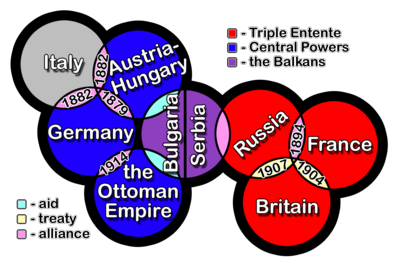

The Austro-Hungerian government blamed Serbia for the assassination on Franz Ferdinand, but they also knew that launching an attack on Serbia would trigger a war with Russia. So the Austrians asked their German allies for support. Germany promised to support Austria if war erupted.

The Serbs counted on Russia for support, and Russia again counted on France to support them. France was afraid to end up in a war alone against Germany, they needed Russia as an ally so they promised to support Russia if a war broke out.

Austria declared war on Serbia July 28 1914 and Russia immediately mobilized its army including forces on German borders. Germany then declared war on Russia on August 1. and on August 3. on France. The Great War had begun (http://firstworldwar.olemarius.net/index.php?nav=breakout).

Belgians were the first among Great War combattants to make extensive use of armoured cars as a military weapon. During the siege of Antwerp, from mid August to the first week of October 1914, numerous motor vehicles were stripped and rebuilt with armour plating. Machine guns were mounted and even rotating cupolas were fitted. Most vehicles were (re)built by the Minerva Motor Car Company in Antwerp, though other large industrial metal works and manufacturing firms contributed to the war effort.

These armoured vehicles were used for reconnaisance, long distance messaging and for carrying out raids and small scale engagements. Circumstances dictated that the small, outnumbered Belgian Army use these highly mobile armoured cars in guerrilla style hit-and-run engagements against the besieging German army. Not only were they quite effective in conducting raids, blowing bridges and delivering messages to exposed positions, they were extremely photogenic as well, a news editors dream. The British press, playing up the 'Brave Little Belgium' angle in newspapers and magazines, published many photos of Belgian armoured cars in and around Antwerp. (see Minerva Armoured Cars)

After the fall of Antwerp in October 1914 and the retreat to the Yser, the front line stabilised and since a breakthough was not forthcoming, there was little use for a highly mobile armoured car force. The Russian military attaché to the Belgian armed forces suggested that the armoured car force could be of use on the Eastern Front. Following protocol, Czar Nicholas made an official request to King Albert of the Belgians. It was decided to send a force of several hundred Belgians to Russia. Since Belgium and Russia were co-belligerents and not official allies, for legal reasons the Belgian soldiers were to be considered as volunteers in the Russian army.

The Belgian force sailed from Brest on September 22nd 1915 and reached Archangel on October 13, 1915. By way of Petrograd, they were sent to Galicia where they mainly saw action against Austrian forces. The Belgian armoured cars came to be known as effective machine gun destroyers. They continued fighting after the Russian Revolution until the treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed. The Belgian armoured car force was recalled but had a difficult time returning home. The trip back to Archangel being unfeasible, the Belgians, much like the Czech Legion, followed the Trans-Siberian railway, crossed northern China and ultimately arrived in Vladivostok. On April 18th, 1918 they boarded an American vessel, the SS Sheridan and sailed to San Francisco. From there they travelled on a much acclaimed and widely publicized trip through the US and sailed from New York on June 15th 1918, finally reaching Paris two weeks later. Thet were disbanded shortly afterwards (http://histomil.com/viewtopic.php?t=12314).

A Russian officer suggested it and of course King Albert I was always willing to help but the Tsar had to ask first because, since Belgium was a neutral country, the small kingdom and the massive empire were fighting on the same side but not exactly were allies in the strictest sense. Also, because of this, on paper at least, the Belgian troops were volunteers in the Russian Imperial Army rather than officially soldiers of the Belgian army for this special mission. In all there were over 300 men who went with the armored cars, motorcycles and bicycles to the Russian front, over time around 400 men were served as troops rotated out. They saw their biggest battles on the Galician front and their speed and firepower were proven to be very good at eliminating Austrian machine-guns positions. These brave men far from home fought even after the Germans had clearly gained the upper hand and they also kept on fighting and doing their duty even after the 1917 Revolution. It was not until the new Russian government made their own peace with the Germans that the Belgians decided it was time to go home.

That was difficult to do because of the revolutionary forces that viewed the Belgian forces as enemies and they blocked the way to all the major ports. The Belgian forces then because of this had to travel across the whole of Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railway to the Pacific where they took a ship to San Francisco, California and then went by train across the United States, being much celebrated along the way, reaching New York and from there sailed across the Atlantic to finally reach Paris two weeks later. In all, their losses were few, only 16 men during all of their fighting and travels were killed (http://histomil.com/viewtopic.php?t=12314).

The Belgian Expeditionary Corps of Armoured Cars in Russia (French: Corps Expeditionnaire des Autos-Canons-Mitrailleuses Belges en Russie) was a Belgian military formation during the First World War which was sent to Russia to fight the German Army on the Eastern Front. Between late 1915 and 1918, 444 Belgian soldiers served with the unit of whom 16 were killed in action.[1]

As the front line in the west stabilized following the Battle of the Yser, the Belgian army was left with a number of armoured cars that could not be used in the static trench warfare which had emerged along the Belgian-held Yser Front. In early 1915, Tsar Nicholas II formally requested military support from King Albert I and a self-contained unit was formed for service in Russia.[2] As Belgium was not officially an ally of the Russian Empire but a neutral power, the Belgian soldiers in the unit were officially considered as volunteers in the Imperial Russian Army itself.

The first contingent of the Belgian Expeditionary Corps, 333 volunteers equipped with Mors and Peugeot armoured cars, arrived in Archangel in October 1915.[1] The unit fought with distinction in Galicia and was mentioned in the Order of the Day five times.[3]

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the Belgian force remained in Russia until the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk withdrew Russia from the war. After the ceasefire, the unit found itself in hostile territory. As the route north to Murmansk was blocked, the soldiers destroyed their armoured cars to prevent their capture by Bolshevik forces.[3] The unit finally reached the United States through China and the Trans-Siberian railway in June 1918.[1]

A similar, slightly larger British unit, the Armoured Car Expeditionary Force (ACEF), also served in Russia during the same period (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belgian_Expeditionary_Corps_in_Russia).

(Over the Top: Alternative Histories of the First World War Door Spencer Jones,Peter Tsouras; blz. 138) (http://landships.activeboard.com/t4968671/belgian-armoured-cars-in-russia/)

When it first set sail, the Belgian armoured car force numbered 333 Belgians, all volunteers. In Russia 33 Russians joined its ranks. Counting reinforcements and replacements, 444 Belgians passed through the ranks. There were 58 vehicules of which 12 were armoured cars plus 23 motor-bicycles and 120 bicycles. 16 Belgians were killed in action in Russia. Only one armoured car was lost. It was captured by German forces and is said to have been used in Berlin during the insurrections in 1919 (http://histomil.com/viewtopic.php?t=12314).

Two Entente companies fought against Central powers in Russian empire front.

The Belgian armored squadron (Corps Expeditionnaire des Autos-Canons-Mitrailleuses Belges en Russie) acted at Russian front from January 1916. It contains of 350 men, 13 armoured cars (Mors and Peugeot : six 37mm cannon-armed, four MG-armed, three not armed), 26 light and heavy cars, 18 motorcycles...

The British Armoured Car Expeditionary Force (ACEF) commanded by Locker-Lampson acted at Russian front from June 1916. It contains of 566 men, 28 armoured cars (12 Lanchester, 2 Rols-Roys, 11 Ford, 4 Pierce-Arrow), 39 different cars, 47 motorcycles... (http://wio.ru/tank/for-rus.htm)

The newly formed Russian Republic continued to fight the war alongside Romania and the rest of the Entente until it was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in October 1917. Kerensky oversaw the July Offensive, which was largely a failure and caused a collapse in the Russian Army. The new government established by the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers, taking it out of the war and making large territorial concessions. Romania was also forced to surrender and signed a similar treaty, though both of the treaties were nullified with the surrender of the Central Powers in November 1918 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_Front_(World_War_I)).

21 March

With 50 divisions now freed by the surrender of Russia, Germany realises that its only chance of victory is to defeat the Allies quickly before the huge human and industrial resources of America are deployed. Germany launches the Ludendorff (or first Spring) Offensive against the British on the Somme.

26 March

The French Marshall Ferdinand Foch is appointed Supreme Allied Commander on the Western Front.

1 April

The Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service are merged to form the Royal Air Force.

9 April

Germany launches a second Spring Offensive, the Battle of the Lys, in the British sector of Armentieres. The front line Portuguese defenders were quickly overrun by overwhelming numbers of German troops. The capture of the Channel supply ports at Calais, Dunkirk and Boulogne could choke the British into defeat (www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/World-War-1-Timeline-1918/).

In the spring of 1918, Luderndorff ordered a massive German attack on the Western Front. The Spring Offensive was Germany’s attempt to end World War One (www.historylearningsite.co.uk/world-war-one/battles-of-world-war-one/the-german-spring-offensive-of-1918/).

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (Kruszewnia, 9 april 1865 – Tutzing, 20 december 1937) was een Duits generaal en politicus.

In de eerste maanden van de Eerste Wereldoorlog behaalde Ludendorf twee grote overwinningen. In de slag om Luik en de slag bij Tannenberg wist hij respectievelijk het Belgische- en Russische leger grote nederlagen toe te brengen. Zijn benoeming in augustus 1916 tot kwartiermeester-generaal maakte hem (met Paul von Hindenburg) het de facto hoofd en de leidende figuur achter de Duitse oorlogsinspanning tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog.

Dit bleef zo tot de keizer in oktober 1918 zijn ontslag aanvaardde. Dit nadat Ludendorff door een monumentale beslissing zowel het einde van de Eerste Wereldoorlog, alsook de val van het Duitse keizerrijk en de start van de Duitse Novemberrevolutie had ingeluid.

Na zich enige tijd in Zweden te hebben teruggetrokken maakte hij in de loop van 1919 zijn rentree in de Duitse politiek. Hij werd een prominent nationalistisch leider en was een van de architecten van de dolkstootlegende. Zowel in 1920 in Berlijn (Kapp-putsch van Wolfgang Kapp) als in 1923 in München (Bierkellerputsch van Adolf Hitler) speelde Ludendorff een actieve rol bij mislukte pogingen tot staatsgreep met als doel om de Weimarrepubliek te elimineren (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Ludendorff).

The 1918 Spring Offensive or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser's Battle), also known as the Ludendorff Offensive, was a series of German attacks along the Western Front during the First World War, beginning on 21 March 1918, which marked the deepest advances by either side since 1914. The Germans had realised that their only remaining chance of victory was to defeat the Allies before the overwhelming human and matériel resources of the United States could be fully deployed. They also had the temporary advantage in numbers afforded by the nearly 50 divisions freed by the Russian surrender (the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spring_Offensive).